|

| Elizabeth Fry from Elizabeth Fry, the angel of the prisons by LE Richards (1916) |

Profile

Elizabeth Fry (née Gurney) (21 May 1780 – 13 October 1845) was a Quaker minister famous for her pioneering work in prison reform. She was featured on the British £5 note from 2001-2016.

An unhappy childhood

Elizabeth Gurney was born in Norwich, Norfolk, on 21 May 1780, one of the 12 children of John Gurney and Catherine Bell. Both her parents were from families that belonged to the Religious Society of Friends, more commonly referred to as the Quakers. John Gurney was a wealthy businessman operating in the woollen cloth and banking industries.

Elizabeth, known as Betsy, was moody, often unwell and tormented by numerous fears. She was dubbed stupid by her siblings for being slow to learn, but was most probably dyslexic. In 1792, Betsy was devastated when her mother died.

Elizabeth, known as Betsy, was moody, often unwell and tormented by numerous fears. She was dubbed stupid by her siblings for being slow to learn, but was most probably dyslexic. In 1792, Betsy was devastated when her mother died.

Conversion

Betsy’s family were ‘gay’ Quakers as opposed to ‘plain’ Quakers. Though they attended the weekly Quaker meetings, they did not abstain from worldly pleasures like the theatre and dancing or wear simple clothes as ‘plain’ Quakers did.

In 1798, an American Quaker named William Savery visited the Friends’ Meeting House in Goat Lane where the Gurneys worshipped. Betsy had a spiritual experience which was strengthened later that year when she met Deborah Darby, a Quaker minister, who prophesied that Betsy would become “a light to the blind, speech to the dumb and feet to the lame.”1

In 1798, an American Quaker named William Savery visited the Friends’ Meeting House in Goat Lane where the Gurneys worshipped. Betsy had a spiritual experience which was strengthened later that year when she met Deborah Darby, a Quaker minister, who prophesied that Betsy would become “a light to the blind, speech to the dumb and feet to the lame.”1

Betsy gradually adopted the ways of a plain Quaker, wearing the simple dress and Quaker cap in which she is depicted on the British £5 note.

In 1811, Betsy became a minister for the Religious Society of Friends and started to travel around the country to talk at Quaker meetings.

Marriage and family

On 19 August 1800, Betsy married Joseph Fry, a plain Quaker whose business was tea and banking. They went to live in Mildred’s Court in Poultry, Cheapside, London, which was also the headquarters for Joseph’s business. In 1808, Joseph inherited the family estate at Plashet in East Ham, further out of London.

It was a fruitful marriage though not always a harmonious one. Joseph and Betsy had 11 children: Katherine (1801), Rachel (1803), John (1804), William (1806), Richenda (1808), Joseph (1809), Elizabeth (1811), who died young, Hannah (1812), Louisa (1814), Samuel Gurney (1816) and Daniel Henry (1822).

Betsy’s prison ministry

Throughout her life, Betsy was active in helping others. At Plashet, she established a school for poor girls, ran a soup kitchen for the poor in cold weather and was the driving force behind the programme for smallpox inoculation in the parish.

In 1813, while living at Mildred's Court, she visited the women’s wing of nearby Newgate Prison for the first time. Betsy was filled with compassion for the awful state of the women and took flannel clothes with her to dress their naked children.

Over the next few years, Betsy’s life was absorbed by family issues, but in 1816, she resumed her visits to the women in Newgate Prison. With the support of the female prisoners, she set up the first ever school inside an English prison and appointed a schoolmistress from among the inmates.

Encouraged by her success, Betsy set out to help the women themselves. She read the bible to them and set up a workroom where the women could make stockings. All the female prisoners agreed to abide by Betsy’s rules. Against all odds, the scheme was successful. The women became more manageable and the atmosphere of the prison was transformed.

Fame and influence

In 1813, while living at Mildred's Court, she visited the women’s wing of nearby Newgate Prison for the first time. Betsy was filled with compassion for the awful state of the women and took flannel clothes with her to dress their naked children.

|

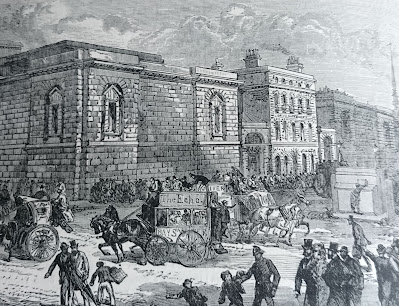

| The front of Newgate Prison from Old and New London Vol II by Walter Thornbury (1872) |

Encouraged by her success, Betsy set out to help the women themselves. She read the bible to them and set up a workroom where the women could make stockings. All the female prisoners agreed to abide by Betsy’s rules. Against all odds, the scheme was successful. The women became more manageable and the atmosphere of the prison was transformed.

|

| Elizabeth Fry in Newgate Prison from Elizabeth Fry, the angel of the prisons by LE Richards (1916) |

News of Betsy’s success spread and she was inundated with requests for advice from prison authorities and ladies who wanted to set up prison visiting.

Over the years that followed, Betsy visited prisons up and down the country, in Scotland, Ireland and on the continent. She became one of the foremost authorities on prison conditions and twice spoke as an expert witness on the subject to Parliamentary Select Committees – in 1818 and again in 1835.

Many of Betsy’s recommendations were included in the Prison Act of 1823 and in 1827 she published Observations on the Visiting, Superintendence and Government of Female Prisoners which became a manual for good management of prisons and prison visiting.

Over the years that followed, Betsy visited prisons up and down the country, in Scotland, Ireland and on the continent. She became one of the foremost authorities on prison conditions and twice spoke as an expert witness on the subject to Parliamentary Select Committees – in 1818 and again in 1835.

Many of Betsy’s recommendations were included in the Prison Act of 1823 and in 1827 she published Observations on the Visiting, Superintendence and Government of Female Prisoners which became a manual for good management of prisons and prison visiting.

Family problems

Betsy found it hard to balance family life with her extensive ministry. She was plagued continuously with ill health and oscillated between periods of intense activity and times of nervous exhaustion and depression. She often had to delegate her domestic responsibilities to her husband and other family members whilst she devoted herself to good works. Although Joseph always supported his wife, he sometimes complained that she neglected him.

The Frys were often forced to economise because of financial problems with Joseph’s business. Betsy’s brothers repeatedly came to their rescue, but in 1828, Joseph was declared bankrupt. They had to move permanently to a much smaller house in Upton Lane, Essex, and Joseph was expelled from the Society of Friends in disgrace.

The Frys were often forced to economise because of financial problems with Joseph’s business. Betsy’s brothers repeatedly came to their rescue, but in 1828, Joseph was declared bankrupt. They had to move permanently to a much smaller house in Upton Lane, Essex, and Joseph was expelled from the Society of Friends in disgrace.

Other areas of ministry

As well as her prison work, Betsy was able to improve the lot of women being transported to Australia for their crimes, providing them with a bundle of belongings to help each woman make a fresh start after their long voyage.

She instigated a project to provide libraries of books for the coastguards whose chief role of preventing smuggling made them isolated and unpopular. This was so successful that the government took over the project and extended it to the navy.

Betsy also set up the first nursing academy, to train nurses who could go into private homes and provide care for those who could not normally afford it.

She instigated a project to provide libraries of books for the coastguards whose chief role of preventing smuggling made them isolated and unpopular. This was so successful that the government took over the project and extended it to the navy.

Betsy also set up the first nursing academy, to train nurses who could go into private homes and provide care for those who could not normally afford it.

A fitting end

Betsy died on 13 October 1845 whilst on a holiday in Ramsgate. Her funeral was held at the Friends’ Meeting House in Barking on 20 October. The funeral procession from her house to Barking was over half a mile long. Even more mourners waited in Barking to celebrate the life of this remarkable woman.

In 1914, a marble statue of Elizabeth Fry was erected inside the Old Bailey in London, on the site of the Newgate Prison where her prison ministry had begun.

In 1914, a marble statue of Elizabeth Fry was erected inside the Old Bailey in London, on the site of the Newgate Prison where her prison ministry had begun.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) From the journal of Elizabeth Fry, 4 September 1798, as recorded in Life of Elizabeth Fry: compiled from her journal, as edited by her daughters, and from various other sources by Susanna Corder (1853).

(2) Corder, De Haan, Hatton and Isba all record Elizabeth Fry's death as the 13 October 1845, but some sources state the 12th.

Sources used include:

Corder, Susanna, Life of Elizabeth Fry: compiled from her journal, as edited by her daughters, and from various other sources (1853)

De Haan, Franciscas, Fry (née Gurney) Elizabeth (1780-1845), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn May 2007, accessed 24 Aug 2015)

Hatton, Jean, Betsy - the dramatic biography of prison reformer Elizabeth Fry (2005)

Isba, Anne, The Excellent Mrs Fry - unlikely heroine (2010)