|

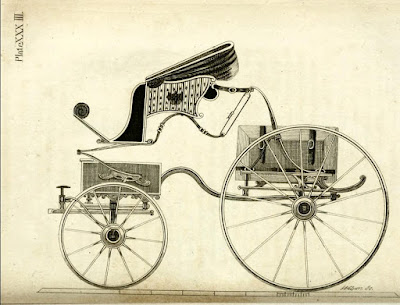

| Ladies in a phaeton from Gallery of Fashion by Nikolaus von Heideloff (1794) |

I have already blogged about travelling chariots here: Travelling chariots. This post looks at that all-important question: what type of carriage would a fashionable gentleman be driving around Hyde Park in 1810, when A Reason for Romance is set?

I had other questions too. What was the difference between a curricle and a phaeton? And between a curricle and a gig? Were these terms hard and fast, or were some of them used interchangeably? Would a fashionable Regency gentleman have been more likely to drive a curricle, a gig or a phaeton?

I have found the second volume of William Felton’s A Treatise on Carriages (1796) particularly good at helping me to differentiate between the vehicles in my mind – but his work also confirms that there is a lot of overlap.

|

| A Dasher! Or the Road to Ruin in the West (5/11/1799) by T Rowlandson after GM Woodward published by R Ackermann |

The most obvious difference between these vehicles was the number of wheels. Gigs, curricles, chaises, whiskeys and chairs all had two wheels whilst phaetons had four.

Beyond this, the differences were the number of horses that usually pulled them, and the size and design of the vehicle.

Phaetons

Let’s start with the phaeton – a light, owner-driven carriage with four wheels.

Felton wrote:

Phaetons, for some years, have deservedly been regarded as the most pleasant sort of carriage in use, as they contribute, more than any other, to health, amusement, and fashion, with the superior advantage of lightness, over every other sort of four-wheeled carriages, and are much safer, and more easy to ride in, than those of two wheels.1

There were two main designs – perch and crane-neck – and these came in a variety of sizes and designs, some high off the ground and some low. A phaeton could be driven by one horse, a pair of horses, or according to some sources, four horses. If pulled by a pair, these might be driven in tandem, with one horse behind the other, as opposed to next to each other as in a normal pair. Some phaetons were drawn by ponies rather than horses.

Felton compared the perch phaeton to the crane-neck:

The perch carriage is of the most simple construction, and considerably lighter than the crane-neck; and as the width of the streets in the metropolis gives every advantage to their use in turning, they are the most general. The crane-neck carriage has much the superiority for convenience and elegance, and every grand or state equipage is this way built; but the weight of the cranes, and the additional strength of materials necessary for their support, make them considerably heavier that the others; but their ease and safety in turning in narrow confined places, and also their strength, render them indispensably necessary for foreign countries.2

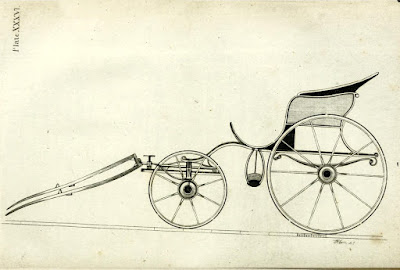

Perch high phaeton

|

| Perch high phaeton from A Treatise on carriages by W Felton (1796) |

In Fanny Burney’s Evelina, Lord Orville drives a phaeton:

Lord Orville drove very slow, and so cautiously, that, notwithstanding the height of the phaeton, fear would have been ridiculous.3

Later, Evelina writes about a visit to Bath:

As I had never had an opportunity of seeing Bath, a party was formed last night for showing me that celebrated city; and this morning, after breakfast, we set out in three phaetons. Lady Louisa and Mrs Beaumont with Lord Merton; Mr Coverley, Mr Lovel, and Mrs Selwyn; and myself with Lord Orville.4

This suggests that some phaetons could comfortably accommodate three people.

In Fanny Burney’s Camilla, Mrs Arlbery drives a phaeton:

'Dear! if there is not Mrs Arlbery in a beautiful high phaeton!'5

Crane-neck phaeton

Felton wrote:

Although there are no established rules for the size of phaetons, yet a proportion should be observed according to the size of the horses, whether fifteen, fourteen, or thirteen hands high; as the appearance of both ought to be conformable to each other, therefore a middling-sized phaeton, to the middling, or Galloway, sized horses, suits best; many persons are very partial to this size of equipage, being less formidable in the appearance than the high, and more elegant than the low, phaeton; from the moderate size of them, they are, in general, called ladies’ phaetons, are best adapted for their amusement.6

The seat is not set so high or far forward in this design.

Middle-sized perch phaeton

|

| Middle-sized perch phaeton from A Treatise on carriages by W Felton (1796) |

Poney or one-horse phaeton (perch)

|

| Poney or one-horse phaeton from A Treatise on carriages by W Felton (1796) |

A pair of ponies from twelve to thirteen hands high are about equal for draught with a horse of fifteen, and a phaeton of the same weight is equally adapted for either. He continued: Poney phaetons are pretty equipages, and are best adapted for parks only; for, by being so low, the passengers are much annoyed by the dust, if used on the turnpike roads; and one-horse phaetons, where one horse only is kept, are much to be preferred to any two-wheeled carriage for safety and ease, but are heavier in draught; to allow for that, it ought to be built as light as possible to be safe with.7

In Pride and Prejudice, Miss de Bourgh drives a low phaeton driven by a pair of ponies:

Miss de Bourgh … is perfectly amiable, and often condescends to drive by my humble abode in her little phaeton and ponies.8

Mrs Gardiner later suggests to Elizabeth that this is her preferred way of travelling around Pemberley:

A low phaeton, with a nice little pair of ponies, would be the very thing.9

Light one-horse or poney Berlin phaeton (crane-neck)

|

| Light one-horse or poney Berlin phaeton from A Treatise on carriages by W Felton (1796) |

For a safe, light, simple, and cheap, four-wheeled phaeton, the Berlin is recommended in preference to any: it is a crane-neck carriage, with the body fixed thereon, at such a distance between the bearings as to be perfectly safe.10

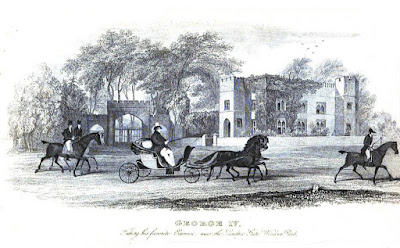

|

| George IV driving his low phaeton in Windsor Park from Memoirs of George IV by R Huish (1830) |

In his book, Carriages and Coaches, Straus wrote that a sociable was ‘merely a phaeton with a double or treble body.’11

Felton wrote that the sociable was so-called

… from the number of persons it is meant to carry at one time. They are intended for the pleasure of gentlemen to use in parks, or on little excursions with their families: they are also peculiarly convenient for the conveying of servants from one residence to another.12

According to Felton, a two-wheeled carriage designed to be drawn by two horses abreast was called a curricle; if designed for one horse, it was called a chaise.

Straus referred to gigs, curricles and chaises in a slightly different way:

As a general rule it may be taken that when a gig had two horses it was called a curricle, and when there was only one, a chaise.13

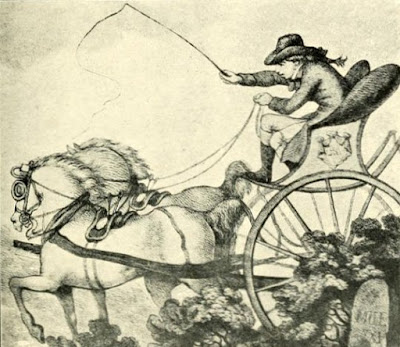

|

| Sir Gregory Gig from print by Bunbury (1782) from Carriages and Coaches by R Straus (1912) |

For lightness and simplicity two-wheeled carriages are preferable, but are less to be depended on for safety; the smallness of their price, and the difference of expence in the imposed duty, are the principal reasons for their being so generally used. They are not so pleasant to ride in as phaetons, as the motion of the carriage frequently gives uneasiness to the passengers. Not having the advantage of the fore wheels, they are neither so safe in their bearings, nor so easy to turn about with, and are therefore inconvenient where the turnings are narrow.14

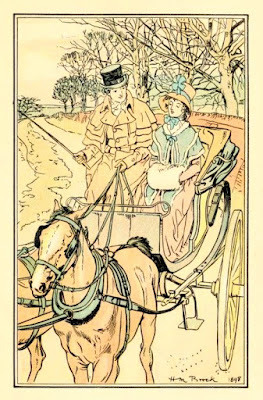

Curricles

A curricle was a light, owner-driven carriage with two wheels designed to be drawn by two horses abreast. There was room only for the driver and a single passenger, and the most fashionable curricles were pulled by a carefully matched pair of horses.

Felton wrote:

Curricles were ancient carriages, but are lately revived with considerable improvements; and none are so much regarded for fashion as these are by those who are partial to drive their own horses; they are certainly a superior kind of two-wheeled carriage, and from their novelty, and being generally used by persons of eminence, are, on that account, preferred as a more genteel kind of carriage than phaetons; though not possessing any advantage to be compared with them, except in lightness, wherein they excel every other, having so great a power to so small a draught. They are built much stronger and heavier than what is necessary for one-horse chaises, and the larger they are the better they look, if not to an extreme.15

The proprietors of this sort of carriage are in general persons of high repute for fashion, and who are, continually, of themselves, inventing some improvements, the variety of which would be too tedious to relate.16

In Hannah More’s Coelebs in Search of a Wife, the hero, Charles, invites Celia to ride in his new curricle. She impulsively invites her sister to join them:

I am sure the curricle will hold us all nicely; for I am very little, and Lucilla is not very big.17

Catherine Morland is invited to ride in Henry Tilney’s curricle on the way to Northanger Abbey:

In the course of a few minutes, she found herself with Henry in the curricle, as happy a being as ever existed. A very short trial convinced her that a curricle was the prettiest equipage in the world; the chaise and four wheeled off with some grandeur, to be sure, but it was a heavy and troublesome business, and she could not easily forget its having stopped two hours at Petty France. Half the time would have been enough for the curricle, and so nimbly were the light horses disposed to move, that, had not the general chosen to have his own carriage lead the way, they could have passed it with ease in half a minute.18

|

| Catherine rides in Mr Tilney's curricle from Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen in The novels and letters of Jane Austen ed RB Johnson (1906) |

In Pride and Prejudice, Mr Darcy drives his sister to meet Elizabeth Bennet in his curricle:

They had been walking about the place with some of their new friends, and were just returning to the inn to dress themselves for dining with the same family, when the sound of a carriage drew them to a window, and they saw a gentleman and a lady in a curricle driving up the street. Elizabeth immediately recognizing the livery, guessed what it meant, and imparted no small degree of her surprise to her relations by acquainting them with the honour which she expected.19

In Sense and Sensibility, the dashing Mr Willoughby drives a curricle:

On their return from the park they found Willoughby's curricle and servant in waiting at the cottage, and Mrs Dashwood was convinced that her conjecture had been just.20

In Mansfield Park, the rich and would-be fashionable Mr Rushworth owns a curricle:

How would Mr. Crawford like, in what manner would he choose, to take a survey of the grounds? Mr. Rushworth mentioned his curricle. Mr. Crawford suggested the greater desirableness of some carriage which might convey more than two.21

In Persuasion, both Charles Musgrove and Mr Elliot own curricles:

They had nearly done breakfast, when the sound of a carriage, (almost the first they had heard since entering Lyme) drew half the party to the window. It was a gentleman's carriage, a curricle, but only coming round from the stable-yard to the front door; somebody must be going away. It was driven by a servant in mourning.The word curricle made Charles Musgrove jump up that he might compare it with his own; the servant in mourning roused Anne's curiosity, and the whole six were collected to look, by the time the owner of the curricle was to be seen issuing from the door amidst the bows and civilities of the household, and taking his seat, to drive off.22

A changeable curricle, or curricle gig

This was a curricle that was designed so it could be used, if necessity required it, by a single horse. This could prove useful when travelling when a horse went lame.

|

| A hooded gig in the National Trust Carriage Museum at Arlington Court |

Felton wrote:

Gigs are one-horse chaises, of various patterns, devised according to the fancy of the occupier; but, more generally, means those that hang by braces from the springs; the mode of hanging is what principally constitutes the name of Gig, which is only a one-horse chaise of the most fashionable make; curricles being now the most fashionable sort of two-wheeled carriages, it is usual, in building a Gig, to imitate them, particularly in the mode of hanging.23

|

| Chair back gig from A Treatise on carriages by W Felton (1796) |

They were prevented crossing by the approach of a gig, driven along on bad pavement by a most knowing-looking coachman with all the vehemence that could most fitly endanger the lives of himself, his companion, and his horse.“Oh, these odious gigs!” said Isabella, looking up. “How I detest them.” But this detestation, though so just, was of short duration, for she looked again and exclaimed, “Delightful! Mr. Morland and my brother!”“Good heaven! 'Tis James!” was uttered at the same moment by Catherine; and, on catching the young men's eyes, the horse was immediately checked with a violence which almost threw him on his haunches, and the servant having now scampered up, the gentlemen jumped out, and the equipage was delivered to his care.24

Mr Thorpe boasts about his gig to Catherine:

What do you think of my gig, Miss Morland? A neat one, is not it? Well hung; town-built; I have not had it a month. It was built for a Christchurch man, a friend of mine, a very good sort of fellow; he ran it a few weeks, till, I believe, it was convenient to have done with it. I happened just then to be looking out for some light thing of the kind, though I had pretty well determined on a curricle too. He continued: Curricle-hung, you see; seat, trunk, sword-case, splashing-board, lamps, silver moulding, all you see complete; the iron-work as good as new, or better.25

In Pride and Prejudice, Mr Collins has a gig:

While Sir William was with them, Mr. Collins devoted his morning to driving him out in his gig, and showing him the country.26

In Persuasion, Admiral Croft has a gig:

This long meadow bordered a lane, which their footpath, at the end of it was to cross, and when the party had all reached the gate of exit, the carriage advancing in the same direction, which had been some time heard, was just coming up, and proved to be Admiral Croft's gig. He and his wife had taken their intended drive, and were returning home. Upon hearing how long a walk the young people had engaged in, they kindly offered a seat to any lady who might be particularly tired; it would save her a full mile, and they were going through Uppercross. The invitation was general, and generally declined. The Miss Musgroves were not at all tired, and Mary was either offended, by not being asked before any of the others, or what Louisa called the Elliot pride could not endure to make a third in a one-horse chaise.27

Gig curricle

In the same way that a curricle gig was designed for two horses and occasionally used with one, so a gig curricle was designed for one horse and occasionally used with two.

Chair

|

| Gig curricle from A Treatise on carriages by W Felton (1796) |

In his glossary, Felton described a chair as:

A light chaise without pannels, for the use of parks, gardens, &c a name commonly applied to all light chaises.28

|

| Rib chair or Yarmouth cart from A Treatise on carriages by W Felton (1796) |

In a letter from Southampton dated 7 January 1807, Jane wrote:

We expected James yesterday, but he did not come; if he comes at all now, his visit will be a very short one, as he must return to-morrow, that Ajax and the chair may be sent to Winchester on Saturday.29

In a letter from Godmersham Park dated 3 November 1813, Jane wrote:

I had but just time to enjoy your letter yesterday before Edward and I set off in the chair for Canty., and I allowed him to hear the chief of it as we went along.30

In Jane Austen’s unfinished novel, The Watsons, Emma Watson is waiting for her father’s chair to fetch her after a ball:

Emma was at once astonished by finding it two o'clock, and considering that she had heard nothing of her father's chair. After this discovery, she had walked twice to the window to examine the street, and was on the point of asking leave to ring the bell and make inquiries, when the light sound of a carriage driving up to the door set her heart at ease. She stepped again to the window, but instead of the convenient though very un-smart family equipage, perceived a neat curricle.31

Whiskey

|

| Half-pannel whiskey from A Treatise on carriages by W Felton (1796) |

A lighter sort of a one-horse chaise than usual.32

Felton explained:

Whiskies are one-horse chaises of the lightest construction, with which the horses may travel with ease and expedition, and quickly pass other carriages on the road, for which they are called Whiskies.33

It would seem from the definitions of a whiskey and a chair that there was some overlap which is why the names are sometimes used interchangeably.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian historical romance set in the time of Jane Austen. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. Felton, William, coachmaker, A Treatise on Carriages Volume 2 (1796).

2. Felton, William, coachmaker, A Treatise on Carriages Volume 1 (1794).

3. Burney, Fanny, Evelina or the history of a young lady’s entrance into the world (1778).

4. Ibid.

5. Burney, Fanny, Camilla (1796).

6. Felton, William, coachmaker, A Treatise on Carriages Volume 2 (1796).

7. Felton, William, coachmaker, A Treatise on Carriages Volume 2 (1796).

8. Austen, Jane, Pride and Prejudice (1813).

9. Ibid.

10. Felton, William, coachmaker, A Treatise on Carriages Volume 2 (1796).

11. Straus, Ralph, Carriages and Coaches, their history and their evolution (1912).

12. Felton, William, coachmaker, A Treatise on Carriages Volume 2 (1796).

13. Straus, Ralph, Carriages and Coaches, their history and their evolution (1912).

14. Felton, William, coachmaker, A Treatise on Carriages Volume 2 (1796).

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. More, Hannah, Coelebs in search of a wife (1859, New York) - originally published 1808.

18. Austen, Jane, Northanger Abbey (1817).

19. Austen, Jane, Pride and Prejudice (1813).

20. Austen, Jane, Sense and Sensibility (1811).

21. Austen, Jane, Mansfield Park (1814).

22. Austen, Jane, Persuasion (1817).

23. Felton, William, coachmaker, A Treatise on Carriages Volume 2 (1796).

24. Austen, Jane, Northanger Abbey (1817).

25. Ibid.

26. Austen, Jane, Pride and Prejudice (1813).

27. Austen, Jane, Persuasion (1817).

28. Felton, William, coachmaker, A Treatise on Carriages Volume 2 (1796).

29. Austen, Jane, The Letters of Jane Austen selected from the compilation of her great nephew, Edward, Lord Bradbourne ed Sarah Woolsey (1892).

30. Ibid.

31. Austen, Jane, and another, The Watsons (1977).

32. Felton, William, coachmaker, A Treatise on Carriages Volume 2 (1796).

33. Ibid.

34. Ibid.

Sources used include:

Austen, Jane, Mansfield Park (1814)

Austen, Jane, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion (1817)

Austen, Jane, Pride and Prejudice (1813)

Austen, Jane, Sense and Sensibility (1811)

Austen, Jane, The Letters of Jane Austen selected from the compilation of her great nephew, Edward, Lord Bradbourne ed Sarah Woolsey (1892)

Austen, Jane, and another, The Watsons (1977)

Burney, Fanny, Camilla (1796)

Burney, Fanny, Evelina or the history of a young lady’s entrance into the world (1778)

Felton, William, coachmaker, A Treatise on Carriages Volume 1 (1794) Volume 2 (1796)

More, Hannah, Coelebs in search of a wife (1859, New York) - originally published 1808

Straus, Ralph, Carriages and Coaches, their history and their evolution (1912)

Photos © Regencyhistory.net

And one wonders how much sloppy speech was used at the time consigning a number of different types under a catch-all like 'gig' even as nowadays a lot of people refer to any four-wheel drive as a 'jeep' regardless of whether it's a people-carrying LandRover 120 or a sporty little Freelander. Felton's book is a smashing resource.

ReplyDeleteI quite agree. There are 'rules' but it doesn't mean to say people kept to them!

DeleteDo believe the quote in footnote 27 is from Persuasion.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteOops. Thanks for pointing that out, Teleri. Of course it is from Persuasion - not sure how that one slipped through. Corrected now.

DeleteI am so glad to have found this blog and especially this post, which is very helpful. You have saved me from trying to squeeze three grown men into a gig.So helpful!

ReplyDeleteI found a small "oops" and hope it's OK to point it out. Admiral Croft drove his gig around in "Persuasion," scaring his wife Sophy, and I believe eventually overturning it.

Thanks again.

Thanks Anne. I am so glad you pointed it out. What a silly mistake to make. You are, of course, absolutely right. I have corrected it now.

DeleteWhat an extremely useful article! Would you happen to know if a very sporting gentleman would ever use a curricle for a longer journey? I assume he'd have to send his luggage ahead?

ReplyDeleteIn Northanger Abbey, Henry Tilney drives his curricle from Bath to the Abbey - a distance of 30 miles. Although this is fictional, I think we can be sure Austen's writing was based on her observations. Also, logically speaking, if a gentleman wanted his curricle in town, it would have to be driven there, either by himself or a groom, so curricles must have been used for longer journeys from time to time.

DeleteI very much appreciate the depth of the information you have presented. What I have never seen any one descuss or depict is how people--especially women--managed to climb up into a vehicle like a high perch phaeton. I have seen where some carrisges let down steps, but the design of the phaeton makes it harder to imagine where such steps would go. Any thoughts on the question?

ReplyDeleteA fascinating question. I've had a look at a few accounts in novels and I've found no mention of steps but they must have had some, surely. In Evelina, Lord Orville 'handed us out' and then 'mounted' his high phaeton.

DeleteI read that the phaeton died out in 1850. Would it be completely anacronistic to have the character in my novel be driving one in the 1860s. He would drive something flash. If not a phaeton what might he be driving in 1862?

ReplyDeleteThanks

Richard

Sorry, Richard. My knowledge doesn't extend into the Victorian era. Looking at contemporary novels is a good guide. What were the flash characters driving in Hardy and Dickens and the like? Or just Google it!

DeleteFascinating, I was reading Northanger Abbey and keen to find out what a curricle was, this blogpost answers all my questions and more. Thanks.

ReplyDeleteI'm glad you found this post helpful. I like to include a glossary in my books for words like this, but I guess Jane Austen didn't feel it was necessary!

Delete