Blue John: Britain's Georgian gemstone

Blue John - Millers Vein - from Treak Cliff, Castleton on display in Buxton Museum

One of the less well known facts about Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire and leader of fashion in the late eighteenth century, was that she collected rocks.

Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire (painting in the South Sketch Gallery)

Visitors to Chatsworth, home of the Duke of Devonshire, can view her mineral collection, along with vases and bowls made from Britain's rarest semi-precious stone, Blue John.

The mineral became hugely popular with craftsmen and their customers in the late Georgian period, and coincidentally its only known source was just a few miles from Chatsworth, in the hills above Castleton.

Display case of minerals in South Sketch Gallery, Chatsworth

Blue John is found nowhere else in the world. It is still mined today, but only in tiny quantities as very little remains in the ground. The two remaining mines, which are mainly natural caverns, are now largely tourist attractions.

The beginnings of Blue John mining

Lead has been mined around Castleton for hundreds of years, possibly even by the Romans, and mining records began in 1280. But there is no reference to the mining and use of Blue John before the 1760s. Trevor Ford, in his book Derbyshire Blue John, explores and debunks stories of Blue John ware being found in Roman Pompeii.

Blue John is a form of fluorspar, a common mineral that occurs in many colours. What makes it unique to Derbyshire is the particular colouring, with bands of purple and blue, yellow and off-white. Formed in the cracks within limestone, no two sections of Blue John are alike.

Blue John spar, Buxton Museum

Where the bands of Blue John reached the surface, they would have been visible. Seventeenth century travellers refer to azure or sapphire spar being found in the Peak District but say nothing about it being mined or used in any way.

All that changed in the 1760s, when the name 'Blue John' appeared in guidebooks and the mineral was used in ornaments. Robert Adam inlaid Blue John into fireplaces at Kedleston Hall and manufacturer Matthew Boulton used it extensively.

In his Sketch of a Tour, dated 1777, William Bray wrote of a mine near Castleton: "They get out of it some blue-john, used by the polishers for making vases etc." [1]

Blue John urn, Buxton Museum

How Blue John was mined

The lead miners of Castleton must have observed Blue John as they went about their business underground. In naturally formed caverns, loose pieces of both lead and Blue John would be mixed in with the silt that filled the caves, and which the miners dug out and searched through for minerals.

Entrance to the Blue John Cavern at Mam Tor, Castleton in Derbyshire

Digging Blue John out of the cave walls demanded some skill, as it is relatively fragile. The limestone around the mineral would have been chipped away to release it, with miners using various techniques to break into the rock walls.

One of these ways was to push wooden pegs into cracks, then soak the wood with water, causing it to swell and break the crack open further. Another approach was to light a fire against a wall, leave it to burn overnight, then throw water against the wall. The sudden change in temperature would cause it to crack.

Blue John vein in the rock, Blue John Cavern

Having been extracted, Blue John had to be dried for a year or two before it could be worked without damaging it structure. Because it is relatively soft, Blue John is easily damaged. Many objects are coated in resin to protect them and the process of applying this resin was often regarded as a trade secret.

While they are tourist caverns today, the mines held little to interest Georgian visitors. William Bray seems to be have been persuaded to go down during his tour and records: "The descent, however, is dirty and difficult, and there is not any thing at the bottom worth seeing."1

The popularity of Blue John

"I have found a new use for Blew John," wrote Matthew Boulton in 1768, which was to turn it into vases. His intent was expressed in a letter, in which he asked someone to enquire about the possibility of leasing a Blue John mine. He also asked that his contact not reveal the name of Boulton as part of the enquiry: "I beg you will be quite secret as to my intentions."2

Blue John milk pail, Buxton Museum

A year later, Boulton bought 14 tons of best quality Blue John, from which he made vases, candelabra and other ornaments. Some survive in Britain's great houses, including Buckingham Palace.

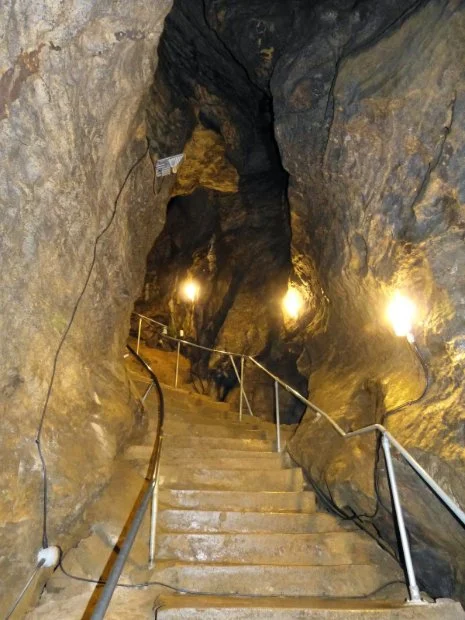

A tourist trade developed around the Blue John mines in the early 1800s, although going underground remained difficult. It wasn't until 1836 that a new, easier path was cut through the rock into the Blue John Cavern mines, and concrete steps were not laid until the early twentieth century.

Inside the Blue John Cavern today (2014)

William Adam had plenty to say about Blue John in his book The Gem of the Peak, or Matlock Bath and its vicinity, first published in 1838. He noted that a tour of the mine cost one shilling per person, and that "the descent is very rapid and over very rough but safe steps, down which a rail is carried for the passage of the mining wagon."3

But by the time Adam was exploring the Blue John mines, the mineral was already starting to fall from favour and the latter half of the nineteenth century saw the small industry decline sharply. The stone is still being mined today, although in very small quantities. The supply of this rare mineral, highly prized by Georgian gentry, could be exhausted within the next decade.

Georgian examples of Blue John

Here are some of the places where you can see Blue John being used in Georgian decorative objects:

Chatsworth House

Unsurprisingly, given its proximity to the source of Blue John, the house contains several vases and other ornaments and even a window made of Blue John. The collection includes the Chatsworth Tazza, the largest single-piece ornament, made in 1842, and currently on display in the dining room. The house also contains the Shore vase, made in 1815, although it's not clear whether this is on public display.

The Chatsworth Tazza, Chatworth, made from Blue John

Hinton Ampner, Hampshire

The house is home to an impressive collection of Georgian decorative objects, including several made from Blue John.

Natural History Museum

Here you can see several Blue John vases. According to Ford, the collection includes what is probably the largest Blue John vase ever made, created by John Vallance around 1840.

Lauriston Castle, Edinburgh

This museum houses a collection of over 80 Blue John ornaments from the late eighteenth century.

Fireplaces containing Blue John can be found at Kedleston Hall and the Georgian House Museum in Bristol (see below). Others exist, but are less accessible to the public.

Blue John fire surround in the study of the Georgian House Museum, Bristol

Andrew Knowles researches and writes about the late Georgian and Regency period. He’s also a freelance writer and editor for business. He lives with his wife Rachel, co-author of this blog, in the Dorset seaside town of Weymouth.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) From Sketch of a Tour into Derbyshire and Yorkshire by William Bray (1777).

(2) Quoted in Derbyshire Blue John by Trevor Ford (2005) p64.

(3) From The Gem of the Peak by William Adam (1838).

Sources used include:

Adam, William, The Gem of the Peak or Matlock Bath and its vicinity (1838, this 6th edition 1857)

Bray, William, Sketch of a Tour into Derbyshire and Yorkshire (1777, this 2nd edition 1783)

Ford, Trevor D, Derbyshire Blue John (Landmark Publishing, 2005)

Castleton Historical Society Harrison, Peter C, Some Castleton History and Things Remembered (2010) PDF

Bulletin of the Peak District Mines Historical Society, Vol 11, No 5, (1992)

Edinburgh Museums

Natural History Museum