Regency History's guide to Almack's Assembly Rooms

Highest Life in London - Tom & Jerry 'sporting a toe' among the Corinthians at Almacks in the West by IR & G Cruikshank in Tom and Jerry: Life in London by P Egan (1869 first pub 1821)

The importance of Almack’s

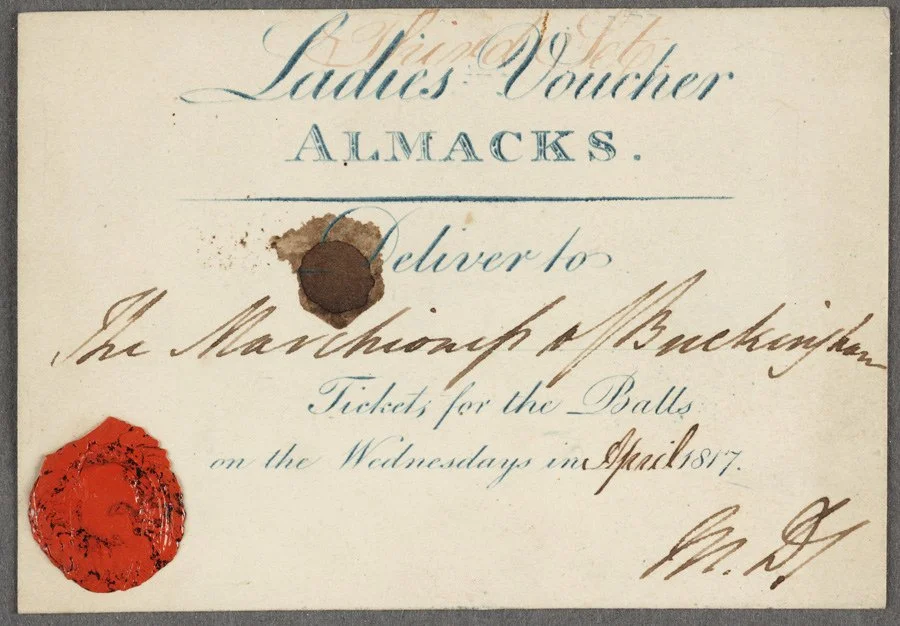

During the Regency period, Almack’s Assembly Rooms were at the heart of the London season. Their importance cannot be overstated. Possessing a voucher to enter the sacred portals of the rooms could make or break a young lady’s entrance into the ton and her chances of finding a suitable husband.

Captain Gronow declared in his reminiscences of 1814:

At the present time one can hardly conceive the importance which was attached to getting admission to Almack's, the seventh heaven of the fashionable world.1

According to Lord Lamington:

Almack's was the portal to that select circle of intellect and grace which constituted the charm of Society.2

The early days

Almack’s Assembly Rooms opened on 12 February 1765 in King Street, St. James's, in the heart of fashionable London.3

They were situated immediately to the east of Pall Mall Place and comprised

… three very elegant new-built rooms, a ten-guinea subscription, for which you have a ball and supper once a week for twelve weeks.4

Willis's Rooms from Old and New London by E Walford (1878)

The rooms were named after their founder, a Scotsman named William Almack.5

Almack also owned The Thatched House Tavern and founded a club for gentlemen that later became Brooks’s. On his death in 1781, the management of the rooms passed to Almack’s niece and her husband, Mr Willis.

During the first phase of the life of Almack’s, the rooms were home to a ladies’ club, where both sexes met to gamble, whilst dancing went on in the great room. It rivalled Carlisle House, whose entertainments, run by the redoubtable Madame Cornelys, were becoming increasingly scandalous. Almack’s combated the mixed nature of the Carlisle assemblies by developing an exclusiveness that set it apart.

When the Pantheon opened in 1772, Almack’s suffered a loss of popularity. Twenty years later, in January 1792, the Pantheon burned down and although rebuilt, it never rivalled Almack’s again.

The exclusive club of the ton

From the 1790s onwards, Almack’s entered a new phase. The excessive gambling disappeared, and the rooms became entirely given over to dances and assemblies. The exclusivity of the rooms increased and Almack’s became the place for a young lady to be seen to demonstrate her position in the ton and for a gentleman to go in search of a wife of good social standing. Hence, it was sometimes referred to as ‘The Marriage Mart’.

Almack’s exclusivity stemmed from the way that it restricted its membership. To attend a ball at Almack’s, it was necessary to procure a voucher, signed by one of the patronesses, and the patronesses kept lists of who was ‘in’ and who was ‘out’.

A genunie Almack's voucher used with kind permission STG Misc. Box 7 (Almack's Voucher) © The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA

You can read more about the vouchers here: A genuine Almack’s voucher.

To be offered a voucher meant acceptance into the ton; to lose one’s voucher indicated social ostracism. This lasted until around 1824 when the exclusive nature of the club began to lessen.

As the English poet and wit, Henry Luttrell wrote in Advice to Julia (1820):

All on that magic List depends;

Fame, fortune, fashion, lovers, friends;

'Tis that which gratifies or vexes

All ranks, all ages, and both sexes.

If once to Almack's you belong,

Like monarchs you can do no wrong;

But banished thence on Wednesday night,

By Jove, you can do nothing right.6

When were the balls held?

The timing and frequency of the balls varied over time, but by 1818, a pattern of weekly balls held on Wednesday evenings during the season had been established.

According to Leigh’s New Picture of London (1818):

The balls at Willis's rooms, commonly called Almack's, are held every Wednesday during the season. They are very splendid, and are very numerously and fashionably attended. Some ladies are styled lady patronesses of these balls; and in order to render them more select, (the price being only seven shillings,) it is necessary that a visitor's name should be inserted in one of these ladies' books, which of course makes the admission difficult.7

The patronesses of Almack’s

Sarah Villiers, Lady Jersey © Rachel Knowles

The lady patronesses changed over time. Seven are mentioned in Gronow’s often-quoted list:

… the Ladies Castlereagh, Jersey, Cowper, and Sefton, Mrs Drummond Burrell, now Lady Willoughby, the Princess Esterhazy, and the Countess Lieven.8

They were not, however, all patronesses in 1814 as Gronow suggested. Other patronesses included the Marchioness of Salisbury and Lady Downshire.

According to Ticknor, writing in 1819, one of the ladies acted as the patroness of each ball.9

Vouchers were granted to those who met the criteria of the patronesses. This depended more on position in society, address, and behaviour than on wealth. If granted a voucher, a young lady could be introduced to suitable partners by the patronesses.

The first quadrille at Almack's c1815 from The Reminiscences and Recollections of Captain Gronow (1889)

The rules of Almack’s

Once your name was entered on the hallowed list and a voucher issued, you could purchase a ticket. For entry to Almack’s, you needed both a voucher and a ticket.

Luttrell wrote in his Advice for Julia (1820):

Suppose the prize by hundreds miss’d

Is yours at last. – You’re on the list. –

Your voucher’s issued, duly signed;

But hold – your ticket’s left behind.

What’s to be done? There’s no admission.

In vain you flatter, scold, petition,

Feel your blood mounting like a rocket,

Fumble in vain in every pocket.

‘The rule’s so strict, I dare not stretch it,’

Cries Willis, ‘pray, my lord, go fetch it.’10

By 1819, a rule was introduced that forbade entry to the rooms after 11 pm. Ticknor recounted the story of how the Duke of Wellington was famously turned away by Lady Jersey for arriving at seven minutes past eleven. Later, this rule was relaxed, and Ticknor recorded that in 1835, the doors were closed at midnight.

Another rule was dress. According to Captain Gronow, in 1814, there was a rule

… that no gentleman should appear at the assemblies without being dressed in knee-breeches, white cravat, and chapeau bras.11

Gronow wrote that the Duke of Wellington was once turned away for wearing trousers but I am inclined to doubt his memory as it seems unlikely that the Duke was turned away for being late and for wearing trousers and Ticknor is generally considered the more reliable source.

According to Moers, Almack’s served

… positively meagre refreshments: weak bohea, weak lemonade for variety, thin slices of brown bread and butter, biscuits and stale cake.12

Only country dances – both Scotch reels and English country dances - were performed until about 1815 when Lady Jersey introduced the quadrille and the Countess Lieven introduced the waltz.

Updated 12 June 2020

Rachel Knowles writes faith-based Regency romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew, who co-writes this blog.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. Gronow, Captain RH, The Reminiscences of Captain Gronow (1862).

2. Chancellor, E. Beresford, Memorials of St. James’s Street and Chronicles of Almack’s (1922).

3. Date from Walpole, Horace, The Letters of Horace Walpole, edited by P Cunningham, in eight volumes (1857) Volume 4 (1762-66) and confirmed by Gronow. Some sources say 13th or 20th.

4. In a letter from Gilly Williams to George Selwyn, 22 February 1765, in Jesse, John Heneage, George Selwyn and his contemporaries (1843).

5. EB Chancellor wrote that his name may have been a pseudonym to disguise his Scottish origins, as anything Scottish was out of favour at this time.

6. Luttrell, Henry, Advice to Julia(1820).

7. Leigh, Samuel, Leigh's New Picture of London (1818).

8. Gronow, Captain. The Reminiscences and Recollections of Captain Gronow (1862).

9. Ticknor, George, Life, Letters, and Journals of George Ticknor (1876).

10. Luttrell, Henry, Advice to Julia (1820).

11. Gronow, Captain. The Reminiscences and Recollections of Captain Gronow (1862).

12. Moers, Ellen, The Dandy (1960).

Sources used include:

Chancellor, E. Beresford, Memorials of St. James’s Street and Chronicles of Almack’s (1922)

Gronow, Captain. The Reminiscences and Recollections of Captain Gronow (1862)

Jesse, John Heneage, George Selwyn and his contemporaries (1843)

Leigh, Samuel, Leigh's New Picture of London (1818)

Luttrell, Henry, Advice to Julia (1820)

Moers, Ellen, The Dandy (1960) Ticknor, George,

Life, Letters, and Journals of George Ticknor (1876) The Times digital archive.