Mary Anning, fossilist (1799-1847)

Mary Anning statue, Lyme Regis (2022)

Profile

Mary Anning (21 May 1799 - 9 March 1847) was a famous fossilist who lived in Lyme Regis, Dorset.

Family background

Mary Anning was born in Lyme Regis, Dorset, on 21 May 1799, one of only two surviving children of Richard and Mary Anning. The other was her brother, Joseph, who was three years older. Richard was a carpenter who supplemented his income by finding and selling curiosities – bones and fossils he had found in the cliffs, which he sold as mementoes of Lyme. They attended the Congregational chapel for dissenters in Coombe Street.

Ammonites found on the beach at Charmouth, Dorset (2025)

A miraculous escape

On 19 August 1800, Mary had a close brush with death. Elizabeth Haskin, her nurse, had taken the fifteen month old Mary up to the Rack Field to get some air and watch a display of horse riding. There was a violent storm and the girl sheltered underneath some elm trees with Mary in her arms. Elizabeth and two other girls were struck dead by lightning. Miraculously, Mary was taken home to her mother alive.

Flood waters

The family lived in a house on the bridge in Lyme very near to the sea. On one occasion, it is said that the house was badly flooded, completely washing away the staircase, and the family had to be rescued through a window.

Bridge, Lyme Regis (2013)

Death of Mary’s father

In 1810, Richard had an accident, falling over a cliff in Lyme. He died that winter from the combined effects of the injuries he sustained and consumption. Mary’s mother made some money from lace making, but the family were in dire poverty and were in receipt of parish relief from 1811 to 1816.

Fossil hunting

Mary and Joseph started looking for curiosities as their father had taught them. Joseph was active in the fossil hunting business until about 1825; Mary hunted fossils for the rest of her life. It is said that her dog, Tray, guarded her finds while she went away to employ diggers to help her extract them.

Fossil on Portland beach, Dorset (2015)

The first ichthyosaur

In the winter of 1810-1811, Mary and her brother Joseph discovered what they thought was a crocodile head; it was actually the head of an ichthyosaur.

The following winter, when the weather and tides finally allowed it, Mary went back to Black Ven and located the rest of the ichthyosaur. It was not the first one ever found, as has sometimes been reported, but it was in excellent condition. It was not named until about 1817, when Professor Buckland said it resembled a lizard and Cuvier, a fish-lizard or ichthyosaurus.

The Western Flying Post reported on 9 November 1812:

A few days ago, immediately after the late high tide, was discovered, under the cliffs between Lyme Regis and Charmouth, the complete petrification of a crocodile, 17 feet in length, in a very perfect state. It was dug out of the cliff nearly on a level with the sea, about 100 feet below the surface of the earth. 1

The ichthyosaur was sold to Mr Henley, the lord of the manor, for £23. It was then acquired by William Bullock for his Museum of Natural History in London. When Bullock’s collection was sold in 1819, the British Museum bought it for £47 5s and it then passed to the Natural History Museum when this became a separate entity.

Fossil hunting friends

Three spinster sisters from the Philpot family started to gather fossils in the Lyme area from around 1817 and became friends with Mary.

Another fossil gathering friend was a Life Guards officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Birch, who was a keen collector. In May 1820, Birch held a sale at Bullock’s in Piccadilly of all his finds. The sale attracted worldwide interest. A very complete ichthyosaur that Birch had bought from the Annings was sold for £100 to the Royal College of Surgeons. Birch donated the £400 raised to the Annings, whom he had discovered were about to sell their furniture in order to pay their rent.

Lyme Regis from The History of Lyme Regis by G Roberts (1823)

The British Museum is troublesome

In 1821, the British Museum refused to spend £100 on the near-perfect skeleton of a five-foot long ichthyosaur, despite pressure from the eminent geologist Henry de la Beche, who knew Mary well, having grown up in Lyme Regis. They bought an inferior one for £50 which Mary’s mother had problems getting paid for! The £100 ichthyosaur was sold to a consortium of nine Bristol purchasers, who gave it as a gift to the new Bristol Institution in 1823.

The plight of the hunter

Mary Anning received very little recognition as the “hunter” of the fossils; all the credit was given to the “gatherers” - those that had bought them. She was mentioned in the Bristol Mirror in 1823 in relation to the Bristol Institution which said that they owed the specimen to:

...the persevering industry of a young female fossilist of the name of Hanning of Lyme in Dorsetshire and her dangerous employment. 2

A plesiosaurus for the Duke of Buckingham

Mary continued to look for fossils. On 10 December 1823, she found a near-perfect plesiosaurus – a long-necked sea dragon - which she sold to Richard Grenville, later 1st Duke of Buckingham, for somewhere in the region of £100 to £200. This caused some controversy as Georges Cuvier initially accused her of fraud. In the end, he was satisfied, and Mary’s reputation soared.

Fossil ink

In 1828, Mary discovered that the ink of fossilized squid-like animals had survived and if these were macerated, the ink could be used to make drawings of the fossils with ink that was contemporary to the finds. This was a great tourist attraction for Lyme. She was also involved in William Buckland’s work on coprolites – the fossilized faeces of reptiles.

Belemnites found on the beach at Charmouth, Dorset (2022)

More trouble with the British Museum

In December 1828, Mary found a pterodactyl – a flying dragon. For some unknown reason, the British Museum was uninterested and so Buckland bought it himself. When Mary discovered a second complete plesiosaurus in 1829, Buckland insisted that the British Museum buy it for 200 guineas.

The Duria Antiquior

In May 1830, Mary’s friend de la Beche prepared the Duria Antiquior, a more ancient Dorset. This was a lithograph that featured the Annings’ finds and was primarily for their benefit: the proceeds from the first print run all went to the Annings.

Duria Antiquior by Henry de la Beche (1830) © National Museum of Wales

More discoveries by the 'fossalist'

In December 1829, Mary discovered a squaloraja – a shark-like creature – and in 1830, a further large-headed plesiosaurus which was purchased for 200 guineas by William Willoughby, Lord Cole, later the Earl of Enniskillen.

Mary supplied both museums and private individuals with her finds and she became known as the fossil woman. On the 1841 census, Mary is listed as living on Broad Street with her mother; both women give their occupation as ‘fossalist’.

What was Mary like?

Mary became something of a tourist attraction in herself. She was known for being helpful to enquirers and scientists alike. Her visitors included the Duke of Saxony who visited on 1 July 1844. But she was something of a character.

Dr Gideon Mantell, a celebrated geologist and palaeontologist, who visited Mary, described her as a

...prim, pedantic, vinegar-looking, thin female, shrewd, and rather satirical in conversation. 3

Anna Maria Pinney recorded in her notebooks of 1831-2 that Mary was liable to marked likes and dislikes and that she complained that people got all the information they could out of her and then went away and made money from it by writing books while she got nothing.

Thomas Allan, the mineralogist, wrote in 1824:

Mary Anning’s knowledge of the subject is quite surprising – she is perfectly acquainted with the anatomy of her subjects, and her account of her disputes with Buckland, whose anatomical science she holds in great contempt, was quite amusing. 4

Honoured at last

In 1838, Mary was awarded a small annuity of £25 per annum, financed by the British Association for the Advancement of Science and a small government grant procured for her by Lord Melbourne, Prime Minister. A further subscription was raised by the Geological Society in London in 1846 after she was diagnosed with cancer.

In July 1846, Mary became the first honorary member of the new Dorset County Museum in Dorchester.

The entrance to the Dorset County Museum, Dorchester (2012)

Mary lived all her life in her home town of Lyme Regis, travelling only once to London in July 1829 when she stayed with Charlotte Murchison, the wife of the geologist. She died on 9 March 1847 from breast cancer, aged 47. She was buried on 15 March 1847 at Lyme Regis Parish Church and was posthumously honoured by a commemorative window in the church in 1850.

De la Beche wrote her obituary in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London in 1848 – an astonishing honour as women were not allowed into membership until 1904!

The only fossil named after her during her lifetime was the acrodus anningiae, a fossil fish species named by the Swiss American naturalist, Louis Agassiz.

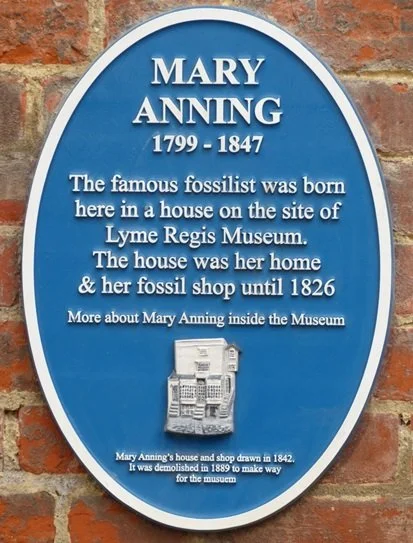

Blue plaque about Mary Anning outside Lyme Regis museum (2013)

Updated 1 July 2022

Rachel Knowles writes faith-based Regency romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew, who co-writes this blog.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

Western Flying Post, 9 November 1812.

Bristol Mirror, 1823.

Curwin, EC (editor), The Journal of Gideon Mantell, Surgeon and Geologist (1940).

Lang, WD, Mary Anning and the pioneer geologists of Lyme, Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society (1939).

Sources used include:

Curle, Richard, Mary Anning (1799-1847), Dorset Worthies no.4 (1963)

Davis, Larry E, Mary Anning: Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness", The Compass: Earth Science Journal of Sigam Gamma Epsilon: Vol 84: Iss 1, Article 8 (2012) Forde, HA, The Heroine of Lyme Regis (1925)

Roberts, G, The History of Lyme Regis, Dorset, from the earliest periods to the present day (1823)

Stinton, Judith, Under Black Ven, Mary Anning's Story (1995)

Torrens, HS, Anning, Mary (1799-1847) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2008, accessed 5 Oct 2012)

Torrens, Hugh, Mary Anning (1799-1847) of Lyme, ‘the greatest fossilist the world ever knew’. British Journal for History of Science, 28, pp257-284

Photographs © RegencyHistory.net