Princess Charlotte, Percy Shelley and High Treason in Derbyshire

|

| Road sign on entering Pentrich, Derbyshire |

A post by my husband Andrew Knowles inspired by a holiday in Derbyshire in October 2014.

Sometimes Regency history takes us by surprise. Only this week, I

learned about a significant historical event that occurred during the Regency and my introduction was via a very modern road sign.

Driving through the small village of Pentrich, Derbyshire, I noticed that the village sign was topped with the phrase: "Revolution 1817." Perhaps you already know about the Pentrich Revolution. I didn't, and here is what I have since discovered.

"The mischiefs flowing from oppression"

Discontent was rife in England during the early nineteenth century. The Industrial Revolution brought unsettling change, the Corn Laws pushed up food prices, and what many considered to be unfair taxes put a huge burden on the working population. Many ordinary people, particularly in the Midlands, considered themselves to be oppressed.

Political agitation for change took various forms. The Luddite movement attacked industrial machines between 1811 and 1813. Debating groups, known as Hampden clubs, sprang up across the country. There was a growing appetite for reform, particularly of the way the nation was governed.

Many wanted to bring about change without violence, but the government was fearful of the large crowds the agitators could muster. The Seditious Meetings Act of March 1817 banned assemblies of more than 50 people.

|

| On a wall opposite the church in Pentrich The plaque reads: "The revolution was plotted at the White Horse Inn which stood near here." |

|

| St Matthew's Church, Pentrich The plaque reads: "The curate hid rebels here from the government troops." |

As they marched, they sought to recruit others and in one encounter, Brandreth killed someone. But as the night wore on and rain soaked his band, their numbers decreased until by dawn, only a small group crossed into Nottinghamshire to face a detachment of the King's Hussars. Some were arrested, while others fled.

|

| The plaque states: "Near here was Widow Hepworth's Farm where a servant was shot dead." |

Another 14 men were sentenced to transportation, from which none ever returned. A further six were imprisoned for up to two years.

"We pity the plumage, but forget the dying bird"

But what about Princess Charlotte and Percy Shelley, as referred to in the title of this post? How are they mixed up in the Pentrich Revolution of 1817?

Princess Charlotte, the only legitimate child of the Prince Regent (later George IV), died on 6 November 1817. Adored by the public, her death in childbirth provoked a huge outpouring of grief across the country.

|

| Princess Charlotte by George Dawe (1817) at the National Portrait Gallery, London |

The poet Percy Shelley made an emphatic connection between these two major events, articulated in his pamphlet "We pity the plumage, but forget the dying bird - an address to the people on the death of Princess Charlotte".1

"LIBERTY is dead"

"Mourn then People of England. Clothe yourselves in solemn black. Let the bells be tolled." A beautiful princess is dead, wrote Shelley, referring at once to both Princess Charlotte and to the notion of liberty.

Charlotte was "young, innocent and beautiful", and "the last and best of her race". Yet, said Shelley, "the accident of her birth neither made her life more virtuous nor her death more worthy of grief". He had no criticism to make of her, but sought to remind people that the deaths of Brandreth, Ludlam and Turner also provoked grief in those that knew them.

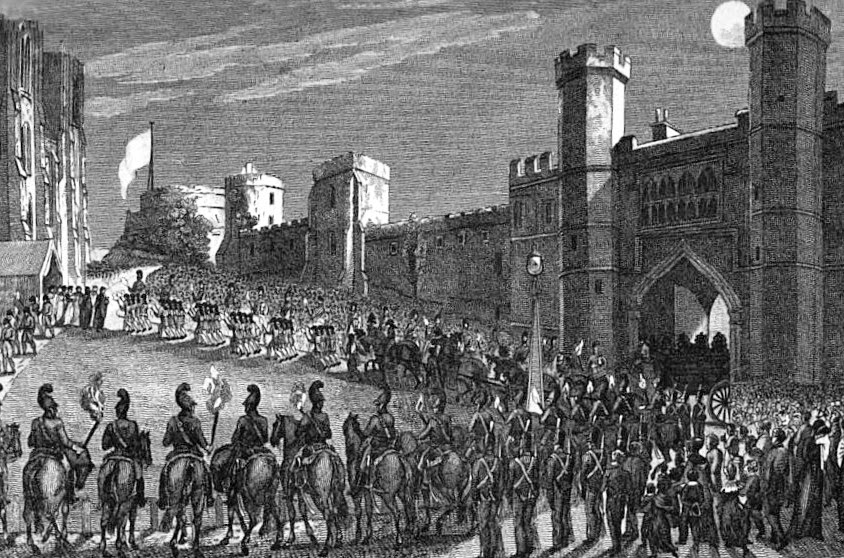

|

| The funeral procession of Princess Charlotte at Windsor from Memoirs of Her Late Royal Highness Charlotte Augusta by Robert Huish (1818) |

He goes on to explain how the government created an oppressive system, with the effect that "the day labourer gains no more now by working sixteen hours a day than he gained before by working eight." It is no surprise to Shelley that people want parliamentary reform and he attacks both the spies who provoked 'rebellion' and the government that dispatched them.

|

| Percy Bysshe Shelley by Amelia Curran (1819) at the National Portrait Gallery, London |

"Our alternatives," he wrote, "are a despotism, a revolution, or reform." In that one sentence Shelley sums up the fears or hopes of so many ordinary people in 1817. It was these hopes that drove the men of Pentrich to commit what would become, in the eyes of the law, High Treason.

All this I have discovered, just because I spotted a word and a date on a road sign.

Notes

(1) The pamphlet is popularly referred to by this title, but the phrase "We pity the plumage, but forget the dying bird" was a motto and was probably never intended to be a part of the title of this pamphlet.

(2) All quotes are from "An Address to the People on The Death of the Princess Charlotte" by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1817).

Sources:

Shelley, Percy Bysshe, The Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley in Verse and Prose, edited by H. Buxton Forman (1880).

The Pentrich Revolution Trail

The Pentrich Rebellion website

The Percy Bysshe Shelley Resource Page

All photographs © Andrew Knowles - www.flickr.com/photos/dragontomato