How would you treat sprains and bruises in the Regency?

A trip to Scarborough by T Rowlandson (1813)

Mr Parker sprains his ankle

At the start of Jane Austen’s unfinished novel Sanditon, Mr Parker sprains his ankle:

A gentleman and lady travelling from Tunbridge towards that part of the Sussex Coast which lies between Hastings and Eastbourne, being induced by business to quit the high road, and attempt a very rough lane, were overturned in toiling up its long ascent half rock, half sand…

The severity of the fall was broken by their slow pace and the narrowness of the lane, and the gentleman having scrambled out and helped out his companion, they neither of them at first felt more than shaken and bruised. But the gentleman had in the course of the extrication sprained his foot—and soon becoming sensible of it, was obliged in a few moments to cut short, both his remonstrance to the driver and his congratulations to his wife and himself—and sit down on the bank, unable to stand.

“There is something wrong here, said he—putting his hand to his ankle.” 1

Fortunately, a gentleman living nearby—Mr Heywood—came to Mr Parker’s rescue:

In a most friendly manner Mr Heywood here interposed, entreating them not to think of proceeding till the ankle had been examined and some refreshment taken, and very cordially pressing them to make use of his house for both purposes.

‘We are always well stocked,’ said he, ‘with all the common remedies for sprains and bruises.’ 2

Unfortunately, Jane Austen didn’t tell us what these remedies were.

So, how would you treat a sprained ankle in the Regency?

The danger of sprains and strains

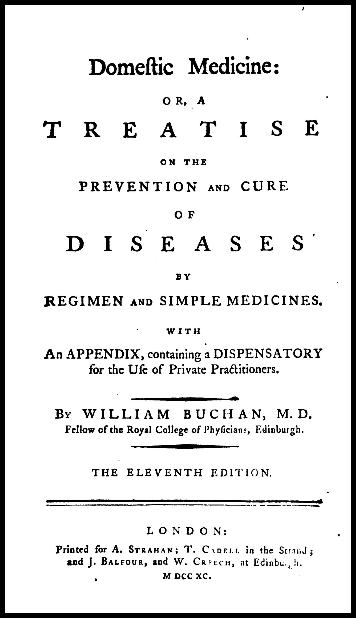

In his 1790 book Domestic Medicine, William Buchan wrote:

Strains are often attended with worse consequences than broken bones. The reason is obvious; they are generally neglected. When a bone is broken, the patient is obliged to keep the member easy, because he cannot make use of it; but when a joint is only strained, the person, finding he can still make a shift to move it, is sorry to lose his time for so trifling an ailment. In this way he deceives himself, and converts into an incurable malady what might have been removed by only keeping the part easy for a few days. 3

How would a you treat a sprained ankle in the Regency?

Dr Buchan prescribed the following remedies for sprains:

1. Immerse in cold water

Country people generally immerse a strained limb in cold water. This is very proper, provided it be done immediately, and not kept in too long. 4

2. Bandage the sprained limb

Wrapping a garter, or some other bandage, pretty tight about the strained part, is likewise of use. It helps to restore the proper tone of the vessels and prevents the action of the parts from increasing the disease. It should not however be applied too tight. 5

3. Bleeding

The treatment of almost every ailment in Georgian times seemed to involve bloodletting or bleeding!

I have frequently known bleeding near the affected part have a very good effect. 6

4. Rest

What we would recommend above all is ease. It is more to be depended on than any medicine, and seldom fails to remove the complaint. 7

5. Poultices

A great many external applications are recommended for sprains, some of which do good, and others hurt. The following are such as may be used with the greatest safety, viz. poultices made of stale beer or vinegar and oatmeal, camphorated spirits of wine, Mindererus’s spirit, volatile liniment, volatile aromatic spirit diluted with a double quantity of water, and the common fomentation, with the addition of brandy or spirit of wine. 8

I discovered that Mindererus’s spirit is an aqueous solution of acetate of ammonium named after a Augsburg physician called Minderer (but I confess that doesn’t actually make me any the wiser as I’m not at all medically minded!).

Relief from the gout W Holland (1801)

Treatment of bruises

Dr Buchan believed bruises were as much a problem as sprains:

Bruises are generally productive of worse consequences than wounds. The danger from them does not appear immediately, by which means it often happens that they are neglected. 9

The remedies Dr Buchan recommended for bruises were somewhat different from sprains, apart from the bleeding.

1. Bathing in warm vinegar

In slight bruises it will be sufficient to bathe the part with warm vinegar, to which a little brandy or rum may occasionally be added, and to keep cloths wet with this mixture constantly applied to it. This is more proper than rubbing it with brandy, spirits of wine, or other ardent spirits, which are commonly used in such cases. 10

2. Cow-dung poultice

In some parts of the country the peasants apply to a recent bruise a cataplasm of fresh cow-dung. I have often seen this cataplasm applied to violent contusions occasioned by blows, falls, bruises, and such like, and never knew it fail to have a good effect. 11

A cataplasm is a poultice or plaster. This sounds like a particularly smelly and unpleasant remedy!

3. Bleeding

When a bruise is very violent, the patient ought immediately to be bled. 12

4. Light food and weak drink

His food should be light and cool, and his drink weak, and of an opening nature; as whey sweetened with honey, decoctions of tamarinds, barley, cream-tartar-whey, and such like. 13

I didn’t know what a tamarind was, let alone a decoction of tamarinds! According to the BBC website, it is a tart fruit from the tamarind tree which tastes like a sour date. The fruit is shaped like a long bean which contains a sour pulp of seeds which can be made into a paste. It is a key ingredient in Worcestershire sauce. 14

I found a recipe for a decoction of tamarinds in Thomas Fuller’s Pharmacopoeia Extemporanea (1719):

A Decoction of tamarinds

Take tamarinds 2 ounces; raisins stoned 4 ounces; boil in fair water 3 pints to 1 quart which strain.

It restrains the Flame of the Blood, allayeth unquenchable Thirst, humects, loosens, and is proper for constant Drink, in those Fevers that bring with them Costiveness, Drought, and parching Heat. 15

5. Vinegary poultice

The bruised part must be bathed with vinegar and water, as directed above; and a poultice made by boiling crumb of bread, elder-flowers, and camomile-flowers, in equal quantities of vinegar and water, applied to it. This poultice is peculiarly proper when a wound is joined to the bruise. It may be renewed two or three times a-day. 16

Leeches, blood-letting and pumping water

In Modern Domestic Medicine (1829), Thomas Graham of the Royal College of Surgeons recommended the following treatment of bruises and sprains:

The best treatment for the slightest kinds of bruises and sprains, consists in giving rest to the part affected, and using one of the embrocations [containing either camphor and tincture of opium, or ammonia], three times a day.

The severer description of bruises will require the application of six or eight leeches to the part, or even make it desirable that eight or ten ounces of blood should be drawn from the arm, the patient afterwards keeping the parts perfectly at rest, and applying a cataplasm [a poultice] of linseed meal and vinegar, or crumb of bread and vinegar.

When all consequent inflammation has subsided, one of the above embrocations may be used with daily friction, It will frequently be necessary , at the same time, to attend to the state of the constitution, supporting it by tonic medicines, and proper diet, when weak, and correcting it by alternatives and aperients, when disordered.

If a weakness be left behind in consequence of a sprain, cold water may be pumped every morning upon the part, and a calico or laced bandage worn to support it. 17

Winter Amusements - A Scene in France (1803) Published by Laurie & Whittle © The Trustees of the British Museum

A sprained ankle in A Reason for Romance

There is a skating scene in A Reason for Romance where my heroine’s sister Eliza falls and badly sprains her ankle. I researched what would have been done and how long such an injury would keep her out of action, because I wanted to know whether it would be reasonable for her accident to make her miss the season.

Of course, one of the best types of research is reenactment. This was not a piece of research I intended to do! No, I wasn’t skating. I merely missed my footing as I stepped outside my front door for my daily exercise during the Covid lockdown of 2020.

Four weeks later, I could walk again, but my leg was still sore, and my ankle a bit swollen and ached if I did too much. I certainly wasn’t up for a ball for a long time afterward and concluded that it was perfectly reasonable that Eliza was forced to miss the entire season as a result of her accident.

My treatment

The treatment of my sprained ankle bore some similarities toimmersing in cold water is a similar idea to ice treatment—I got my frozen peas on my swollen ankle promptly. I used witch hazel gel and later arnica for the swelling and bruises—no bloodletting or cow dung poultices, I hasten to add. I used an elasticated bandage for support but above all, plenty of rest, as recommended by Buchan.

Diana Parker’s remedy

In Sanditon, Mr Parker’s sister, Diana, later hears about his accident and writes to him:

If indeed a simple sprain, as you denominate it, nothing would have been so judicious as friction, friction by the hand alone, supposing it could be applied instantly. Two years ago I happened to be calling on Mrs Sheldon when her coachman sprained his foot as he was cleaning the carriage and could hardly limp into the house, but by the immediate use of friction alone steadily persevered in (and I rubbed his ankle with my own hand for six hours without intermission) he was well in three days. 18

I’m glad Diana didn’t get her hands on my ankle—it sounds very painful!

Post updated 17 August 2025

Rachel Knowles writes faith-based Regency romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew, who co-writes this blog.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

Austen, Jane, Sanditon (1817).

Ibid.

Buchan, William, Domestic Medicine: or, a treatise on the prevention and cure of diseases (1790, 11th edition).

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Fuller, Thomas, Pharmacopoeia Extemporanea or a body of medicines (1719).

Buchan op cit.

Graham, Thomas John, Modern Domestic Medicine (1829).

Austen op cit.

Sources used include:

Austen, Jane, Sanditon (1817)

BBC website

Buchan, WillGraham, Thomas John, Modern Domestic Medicine (1829).iam, Domestic Medicine: or, a treatise on the prevention and cure of diseases (1790, 11th edition)

Fuller, Thomas, Pharmacopoeia Extemporanea or a body of medicines (1719)

Graham, Thomas John, Modern Domestic Medicine (1829)