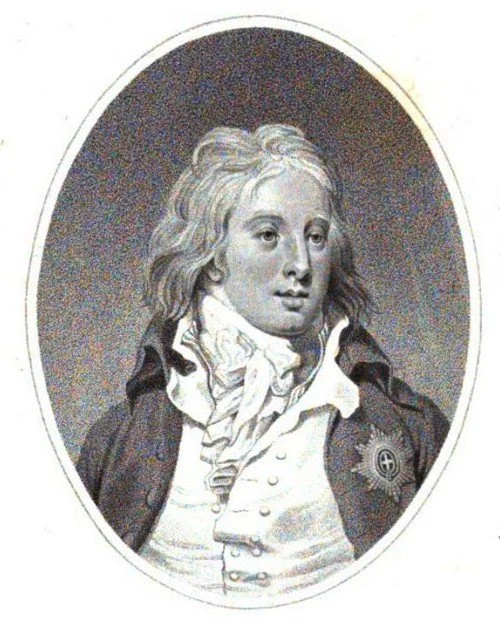

The Six Princesses: Princess Sophia (1777-1848)

Princess Sophia from A Biographical Memoir of Frederick, Duke of York and Albany by John Watkins (1827)

Profile

Princess Sophia (3 November 1777 - 27 May 1848) was the fifth daughter of George III and Queen Charlotte. She never married, but was rumoured to have had an illegitimate son in Weymouth in 1800.

Birth of a fifth daughter

Princess Sophia was born at Windsor Castle on 3 November 1777, the twelfth child of George III and Queen Charlotte. She was christened on 1 December in the grand council room at St James’s Palace by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Sophia was given into the care of a wet nurse, the wife of a Lieutenant Williams, who applied for the position after dreaming that she had been given it. She was appointed when none of the three preferred applicants was able to take up the role.

Princess Sophia from La Belle Assemblée (1807)

A royal upbringing

Sophia was educated with her sisters by various governesses and tutors under the supervision of Lady Charlotte Finch. Her lessons included English, French, German, geography, history, music, art and needlework.

The Princesses were brought up under the austere eye of their watchful mother, constantly chaperoned and allowed very little freedom to develop relationships outside of their family group. In Court, they were expected to stand in the presence of the King and Queen, often for hours at a time.

Character

Sophia was a pretty girl with a fiercely passionate nature, which made her somewhat unruly and inclined to be moody. She was reputedly the favourite sister of the Duke of Clarence and the Duke of Kent, who called her his “dear little angel”. The Duke of Cumberland watched over her with an intensity that was not considered entirely healthy.

Edward, Duke of Kent, from A Biographical Memoir of Frederick, Duke of York and Albany by John Watkins (1827)

The Nunnery

George III was very fond of his daughters, but was in no hurry to see them grow up. He had strong views on what was a suitable match for his beloved daughters; he was vehemently opposed them marrying beneath them or marrying Catholics. This severely limited the options for suitable husbands.

In addition, Queen Charlotte liked to have her daughters in attendance on her, and became particularly reliant on their company as the King’s illness progressed. The Princess Royal finally got married in 1797, but matches for her sisters were not forthcoming. Perhaps if the King had remained well he would have secured them the husbands that they so desperately wanted, but in the event, the younger five Princesses continued unwed.

Sophia was not happy and in 1812, she wrote to her brother, George, the Prince Regent, in her tiny writing, mourning the lot of her unmarried sisters and herself, and thanking him for his kindness to the “four old cats” in the “Nunnery” at Windsor.

Sophia received an offer of marriage from a German prince in 1801, but this was not accepted by her parents and she never married.

Windsor Castle from the Thames from Memoirs of Her Late Majesty Charlotte by WC Oulton (1819)

Forbidden love

Deprived of marriage, the passionate Sophia seems to have fallen in love with one of the few gentlemen she was allowed to meet. General Thomas Garth was one of the King’s equerries, a small man over thirty years her senior, whose face was disfigured by a large purple birthmark over his forehead and around one eye.

Although an unlikely choice for the young Princess, her sister Mary’s teasing gives some credence to the relationship; she referred to Garth’s birthmark as “the purple light of love”. It has been suggested that they may have gone through some kind of secret marriage ceremony, but they never lived together openly, and this remains conjecture.

An illegitimate son?

There is evidence, however, to suggest that in August 1800, Sophia may have given birth to an illegitimate child whilst staying in Weymouth. It would appear that Garth had the opportunity to be alone with Sophia one evening when the King and Queen were in London. Sophia had been ill for some time and was living in the Queen’s Lodge at Windsor, where her bedroom was beneath Garth’s.

Weymouth Bay by Samuel Alken (1803)

Nine months later, Sophia was “brought to bed”, so Lady Bath told Greville. Lady Bath claimed to have the news on the authority of Lady Caroline Thynne who was Mistress of the Robes to the Queen at the time, an honest woman who would have been in a position to know the truth.

It was feared that this distressing news might have a detrimental effect on the King and so he was told that Sophia had dropsy and was then miraculously cured by eating roast beef. The King was almost blind by this time and it is possible that he was unaware of the real state of affairs. Regardless, he seemed to accept what he was told and repeated the story of the miracle cure, saying that it was a “very extraordinary thing”.

Scandalous rumours

The boy believed to be Princess Sophia’s son was christened Thomas and left in Weymouth at the home of Major Herbert Taylor, the Private Secretary to the Duke of York and afterwards to the King. Garth accepted paternity of the boy, and remained in favour at Court, receiving promotion and being appointed to a responsible position in the household of Princess Charlotte. According to Lord Glenbervie, Sophia occasionally visited Thomas.

There was an alternative, far more alarming, story that arose after the original scandal broke in 1829, which suggested that the child was in fact fathered by Sophia’s brother, Ernest, Duke of Cumberland, who had always seemed to have an unnatural interest in his sister. The rumour may have been started by the Princess of Wales, and it appears that some, including the Duke of Kent, believed it. Others have disputed whether Thomas was Sophia’s son at all.

Ernest, Duke of Cumberland from The Lady's Magazine (1793)

A permanent invalid

Throughout her life, Sophia was subject to indifferent health, suffering from spasms and fits of depression that were indicative of her father’s illness. As she grew older, she was inclined to indulge in her invalidism, enjoying the attentions of her brothers who pampered her. The Duke of Kent referred to her as “poor little Barnacles” and the Prince of Wales sent her gifts and visited her.

The influence of Sir John Conroy

On the Queen’s death in 1818, Sophia inherited the Lower Lodge at Windsor, but she chose to live at Kensington, close to the Duchess of Kent and the young Princess Victoria. Both Sophia and the Duchess fell under the influence of the handsome, imposing and ambitious John Conroy.

Sophia was charmed by Conroy’s easy confidence, and his efficiency in protecting her from the impositions of her supposed son, Thomas Garth. Conroy took control of her finances which he proceeded to expend on his own advancement.

Duchess of Kent from La Belle Assemblée (1825)

Such was Conroy’s influence over her that Sophia was persuaded to speak to her brother on his behalf, gaining him the title of Knight Commander of the Hanoverian Order. Unfortunately, her susceptibility to Conroy’s influence alienated her from the young Victoria who hated Conroy’s position in her mother’s household.

Death of a Princess

Notwithstanding her indifferent health, Sophia lived until she was 70. She died at her house in Vicarage Place, Kensington, on 27 May 1848, and was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery in London.

Rachel Knowles writes faith-based Regency romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew, who co-writes this blog.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Sources used include:

Bell, John, La Belle Assemblée, various (1806-1831, London)

Chedzoy, Alan, Seaside Sovereign - King George III at Weymouth, (Dovecote Press, 2003, Dorset)

Hall, Mrs Matthew, The Royal Princesses of England (1871, London)

Hibbert, Christopher, George IV (Longmans,1972, Allen Lane, 1973, London)

Hibbert, Christopher, Queen Victoria (HarperCollins, 2000, London)

Hodge, Jane Aiken, Passion and Principle (John Murray,1996, London)

Oulton, Walley Chamberlain, Authentic and Impartial Memoirs of Her Late Majesty Charlotte, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland (1819, London)

Papendiek, Mrs, Court and private life in the time of Queen Charlotte: being the journals of Mrs Papendiek assistant keeper of the wardrobe and reader to her Majesty, edited by her granddaughter, Mrs Vernon Delves Broughton (1887, London)

Purdue, AW, George III, daughters of (act.1766-1857), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford University Press, 2004, online edn, May 2009, accessed 10 Feb 2012)

Watkins, John, A Biographical Memoir of Frederick, Duke of York and Albany (1827, London)

All photographs © RegencyHistory.net