Did Father Christmas visit Regency England?

Father Christmas by Phiz, illustrator to Dickens and others (British Museum)

Did Jane Austen, the Prince Regent, Fanny Burney or the Duke of Wellington talk of Santa Claus bringing presents at Christmas?

No, they didn’t.

But their December conversations may have made mention of Father Christmas. Or Sir Christmas or Captain Christmas. Because the personification of Christmas as a man who delivered festive cheer was not unusual in late Georgian England.

Here’s what we’ve learned from our research into the Christmas character who now wears a red suit, drives a reindeer sleigh and delivers gifts for children to unwrap on Christmas Day.

Christmas before Father Christmas

In the 20th century lots of British children grew up expecting an annual visit from Father Christmas. We didn’t know him as Santa Claus. We’ll talk about this alternative name a little later on.

Christmas, as a festival of holiday feasting, has been celebrated in England for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. It falls at an agriculturally barren time of year, when nothing grows and there’s little to do except wait for the sun to start warming the ground again.

Before Christianity it wasn’t Christmas, but there’s evidence it was still a festival of some kind. Archaeology suggests that major feasting took place in midwinter near Stonehenge in 2,500 BC.

The Roman feast of Saturnalia started around 17 December. It included elements we associate with later Christmas traditions, such as role-reversal between masters and slaves.

The Saxon Egbert of York, who died in 766, wrote that ‘the English people have been accustomed to practise fasts, vigils, prayers, and the giving of alms both to monasteries and to the common people, for the full twelve days before Christmas.’

From what we’ve researched, there’s no character who personifies these festivals.

Some have suggested the Norse god Odin is an early version of Santa Claus, as he flew through the sky, bringing gifts made by his magical elves. It’s probable that myths like this played a part in the evolution of today’s jolly character with a long white beard.

What we do know is that by the medieval period the festive entertainments included someone with the name Christmas.

Early references to the man Christmas

Father Christmas may have started making an appearance in mummers’ plays of the medieval period. These were informal performances put on by local people, as part of the celebration of festivals such as Christmas.

A character called ‘Sir Christmas’ appears in songs that date from the 15th century. Other titles from around that time are ‘The Christmas Lord’, ‘Captain Christmas’ and ‘Prince Christmas’.

In 1610 Ben Jonson published Christmas, His Masque, a play that features Christmas as a character with ten children. This is a step towards him becoming Father Christmas.

Father Christmas cancelled

England’s Christmas traditions were sharply interrupted by the ordinance, in 1647, that religious festivals be abolished. Three years earlier, in 1644, the government had insisted that Christmas Day be a fast, not a feast.

It’s as the Puritans tried to freeze the feasting out of the festival that Father Christmas makes his first appearance in print. He first pops up in a pamphlet titled The Arraignment Conviction and Imprisonment of Christmas, published 1645. It opens with the line: Honest Crier, I know thou knewest old Father Christmas.

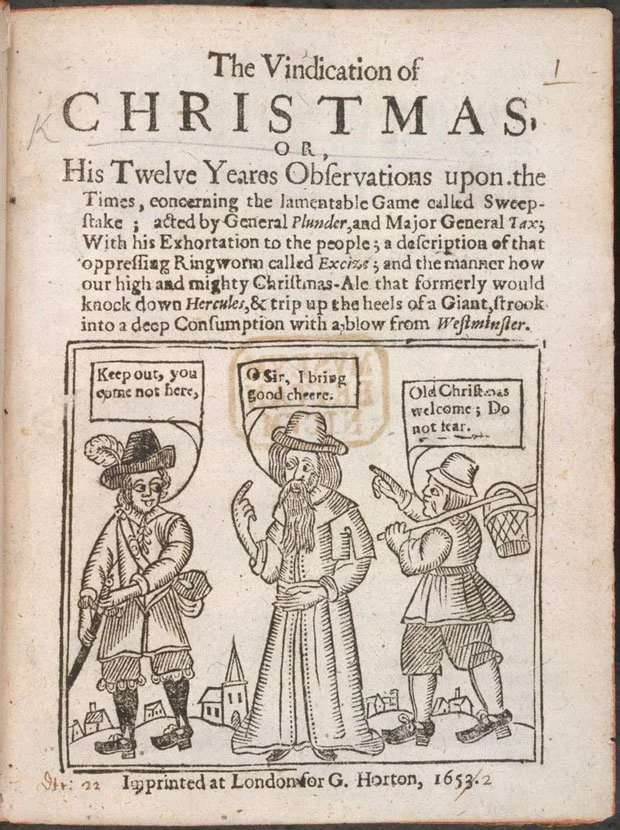

The character of Christmas is seen in another pamphlet, ‘The Vindication of Christmas’, published 1652, by John Taylor. It’s written from the point of view of Christmas, visiting England, described as a ‘lamentable, pitiful, dejected, and headlesse countrey’ after more than a decade under Puritan rule.

‘I was in good hope that so long a misery would have made them glad to bid a merry Christmas welcome.’ He’s not given the title of ‘Father Christmas’, although at one point a blacksmith addresses him as ‘father Christmas’.

Cover of The Vindication of Christmas, with the figure of Father Christmas in the middle, British Library

The Georgian and Regency Father Christmas

By the 18th century Father Christmas had become a formal title for the personification of the festival. A Christmas Tale, published in the Oxford Magazine, 1773, features a character called Father Christmas.

He’s also mentioned in The Vocal Library, a large collection of songs published in 1800, and in other works.

Here are some descriptions of the Georgian Father Christmas.

From The Newcastle Courant, Saturday 18 December 1742.

He enjoys a variety of luxuries, rolling in plenty, partaking of ‘all the Dainties that Art produced, or Nature bestowed,’ with a figure assuming a ‘bulk of importance’.

In The Gloucester Journal of 9 January 1753 he’s described as having a ‘broad rosy face’.

This is from The Theatrical Bouquet, a collection published in 1780. One of the characters addresses the audience:

Behold a personage well known to fame;

Once lov’d and honour’d—Christmas is my name!

He goes on:

Holly, and ivy, round me honours spread,

And my retinue shew, I’m not ill-fed:

Minc’d pies by way of belt, my breast divide,

And a large carving knife, adorns my side;

‘Tis no Fop's weapon, ‘twill be often drawn;

This turban for my head is collar’d brawn!

Tho’ old, and white my locks, my cheeks are cherry,

Warm’d by good fires, good cheer, I’m always merry:

With carrol, fiddle, dance, and pleasant tale,

Jest, gibe, prank, gambol, mummery, and ale,

I, English hearts rejoic’d in days of yore;

For new strange modes, imported by the score,

You will not sure turn Christmas out of door!

In The Morning Herald, Friday 25 December 1829

Hail, Father Christmas! Welcome thou

Tho’ sere and wrinkled is thy brow,

Tho’ wrapt in mist, and frost, and snow,

And piercing winds around thee blow

Yet, Father Christmas, welcome thou!

Red-berried holly round thy head

Is with perennial laurel spread;

A yew staff in thy aged hand,

Like pilgrim from the Holy Land

Christmas, thou’rt welcome in our shed!

Old Father Christmas, as he’s often called, consistently presented as the bringer of merriment and good cheer, associated with feasting and drinking. There’s also a sense that he’s less welcome now than he was in times past.

From what we’ve read, it seems likely that many people in late Georgian and Regency England would be familiar with the idea of Father Christmas. However, he was probably more associated with Christmases of the past than the present.

Charles Dickens and Father Christmas

It’s said that much of our modern Christmas is rooted in the works of Charles Dickens and Washington Irving. We’ll get to Irving below, when we talk about St Nicholas and Santa.

Charles Dicken’s A Christmas Carol must be the second most popular story told at Christmas. The first is, of course, the Nativity, without which there would be no Christmas.

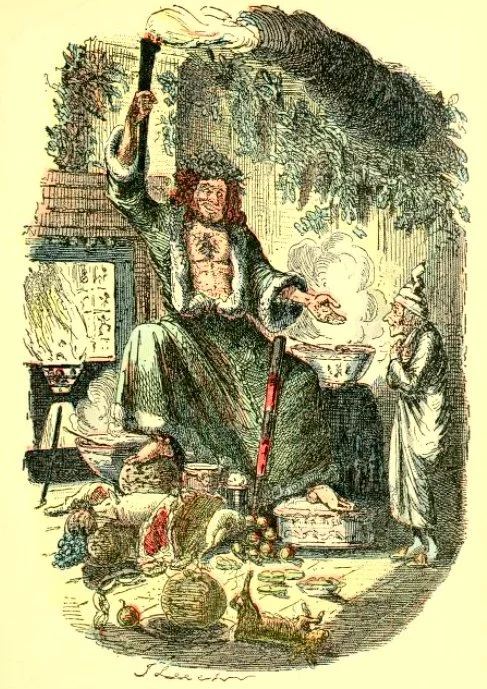

A Christmas Carol was first published in 1843, making it Victorian and not Georgian. But I can’t resist including it here because of its representation of a traditional Father Christmas.

You probably know the story, and if you do, you’ll also know there’s no mention of Father Christmas. But he’s there, right at the heart, as the Ghost of Christmas Present.

Dicken’s describes the Ghost as wearing a ‘green robe, or mantle, bordered with white fur’. He has a holly wreath on his head. He sprinkles incense on dinners, which fosters goodwill. His appearance transforms Scrooge’s room, decorating it with holly, mistletoe and ivy, initiating a roaring fire and heaping up all kinds of food.

The Ghost wears an antique scabbard, rusty with age, and without a sword. I’ve seen it suggested that this indicates his role as a peace-maker. Is there another interpretation?

In the dialogue from A Theatrical Bouquet, quoted above, Christmas wears a carving knife that he says is kept busy, presumably carving meat at the feast. Does the rusty scabbard suggest that Christmas Present hasn’t used his knife for a long time, because he’s been forgotten?

Whatever the meaning of the sword, it’s clear that the Ghost is based on the traditions of Father Christmas, bringer of Christmas cheer for generations. Of course, Dickens adds his own creative genius by transforming him into a ghost, and having him live for just one night.

Ghost of Christmas Present by John Leech from A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens (1920 reprint of original 1843 edition)

Santa Claus arrives in 19th century England

Santa Claus was unknown in Regency England. The earliest reference we can find to him is in Howitt’s Journal of Literature, published 1848. He features in an article about how different nations celebrate New Year’s Eve.

Santa, we’re told, is a Dutch custom that found its way to America. He arrives on New Year’s Eve with gifts for children.

The article goes on:

Santa Claus is no other than the Pelz Nickel of Germany and the North; he is in fact , the good Saint Nicholas of Russia, the patron-saint of children; he arrives in Germany about a fortnight before Christmas.

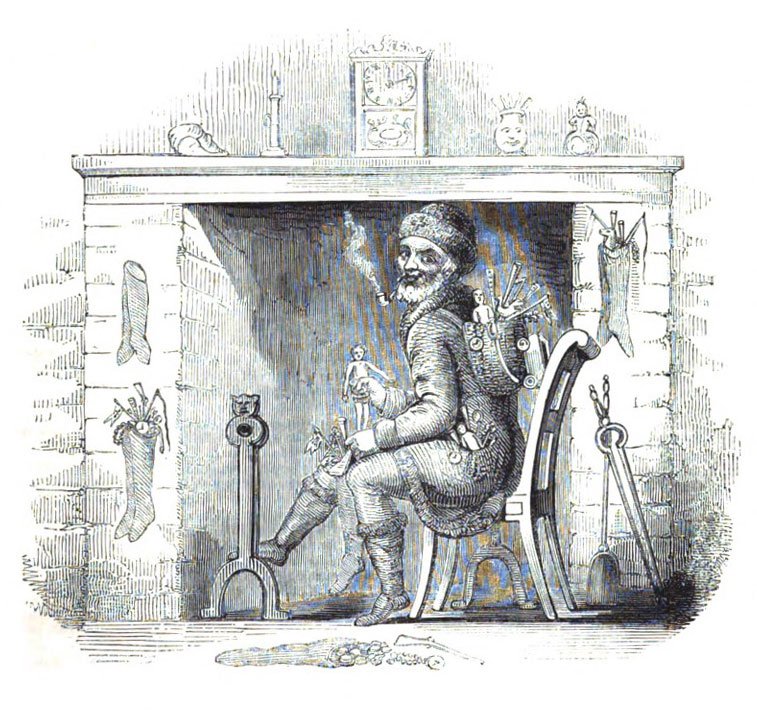

The article in Howitt’s journal credits an American source for informing them about Santa, which includes the picture below. It shows Santa ‘sitting before the empty fire-place of an American house, with his foot on the old fashioned dog, a little after midnight, the family having retired to bed to be out of his way, and having hung up the stockings that he may fill them with gifts.’

While this 1848 article is one of the first (if not the first) mentions of Santa Claus in Britain, he was already quite well known in America by his older name, St Nicholas.

Santa Claus in an American home, as pictured in Howitt’s Journal of Literature (1848)

St Nicholas and Santa Claus

While Santa Claus was unknown in Regency England, he was, as we’ve seen from Howitt’s Journal, not unfamiliar to Americans. Although they may have known him better as St Nicholas.

The original St Nicholas was a bishop of the early church. Very little is known about him, with the earliest accounts of his life written centuries after his death. Tradition has it that he died on 6 December 343.

He’s known for his generosity, and for often leaving gifts in secret. Over time he became patron saint of various communities including sailors, merchants, toy-makers, children and brewers.

Over time St Nicholas became the Dutch Sinterklass. Dressed in a red cape, he brings gifts and carries a book where children are recorded as being good or naughty.

It’s beyond the scope of our research to look into how St Nicholas became Sinterklass, or Santa Claus as we now know him. However, it’s clear that Dutch settlers took St Nicholas traditions with them to America.

It seems that the earliest use of the name Santa Claus (spelled Sancte Claus) is in a poem published in the New York Spectator in 1810.

However, his association with Christmas was strengthened by the writings of Washington Irving and the poem ‘The Night Before Christmas’.

Washington Irving’s comic Knickerbocker’s History of New York, published in 1809, draws on the Dutch traditions of Christmas. In it one of the characters has a dream in which ‘the good St. Nicholas came riding over the tops of the trees, in that self-same wagon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children.’

He also describes hanging up a stocking beside the chimney on St Nicholas Eve (presumably 5 December).

The character of St Nicholas as a sleigh-riding gift giver at Christmas was reinforced by the American poem ‘A Visit from St Nicholas’, more commonly known as ‘The Night Before Christmas’. It’s attributed to Clement Clarke Moore. It was first published, anonymously, in the New York Sentinel on 23 December 1823.

Interestingly, in the three versions of St Nicholas we’ve looked at, he delivered gifts on different days: New Year’s Eve, St Nicholas Eve and Christmas Eve.

As we’ve already noted above, the American tradition of St Nicholas/Santa Claus seems to have crossed the Atlantic in the 1840s.

Victorian image of Santa Claus, 1884

Father Christmas and Santa Claus

Father Christmas was a traditional English personification of Christmas. He’s a folk figure who appears in Christmas plays and poetry for decades before the Regency period.

Perhaps his popularity was in decline in the early 19th century, because for many, Christmas celebrations had become more muted. There are plenty of nostalgic references to ‘old Christmas’ as being something that was lost. But as Dickens shows in A Christmas Carol, he was not entirely forgotten.

Santa Claus springs from the Dutch traditions around Christmas and New Year. They exported their celebration of St Nicholas to North America, where he became more familiar to the English-speaking population. From there he made his way back across the Atlantic.

Later in the 19th century the two characters merged in the Santa Claus/Father Christmas figure of today.

From my research I’m confident that many people in Regency England knew about Father Christmas, and that his role was to bring good cheer and merriment at one of the darkest times of the year. I suspect quite a few invited him into their homes.

Andrew Knowles researches and writes about the late Georgian and Regency period. He’s also a freelance writer and editor for business. He lives with his wife Rachel, co-author of this blog, in the Dorset seaside town of Weymouth.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

Sources used include:

Knickerbocker’s History of New York by Washington Irving (1809)

A Right Merrie Christmass - The Story of Christ-tide (1894)

The Oxford Magaize or Universal Museum, Vol. 10 (1773)

The Vocal Library - Being the Largest Collection of English, Scottish, and Irish Songs, Ever Printed in a Single Volume (1800)

Regency History

by Andrew & Rachel Knowles

We research and write about the late Georgian and Regency period.

Rachel also writes faith-based Regency romance with rich historical detail.