Regency History Guide to Ranks in the Royal Navy

Midshipman Robert Deans in the early 1800s. Displayed at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich (2022).

Everyone knew their place on a Royal Navy ship. From the youngest boy to the most seasoned Able Seamen, from sailors’ wives and occasional passengers to captains and admirals - everyone knew their status and their duties.

The main classes of rank and role aboard ship were:

Sea officers

Warrant officers

Petty officers

Seamen and Landsmen

Marines

The Navy’s system of ranks, roles and promotions was relatively complex, having evolved over time. There were rules and conventions, and then there were exceptions to these.

Social status made it even more complicated. A junior officer, such as a Midshipman, might be the son of an aristocrat or, in the case of William Henry, the son of the king. He joined the Royal Navy in 1778, aged 13. As the third son of King George III, his social status was about as high as you could get, yet his formal rank put him below every other officer aboard.

Sea Officers

Midshipman - the entry-level to becoming an officer. Boys or young men typically began their Navy career with this rank, aged 12-14.

Lieutenant - promotion to this rank was achieved through passing exams.

Commander - previously known as ‘master and commander’, this rank was given to officers put in charge of smaller ships.

Captain - the officer in command of a warship. Sometimes referred to as a post-captain, to show that the officer wasn’t a more junior officer who’d been appointed to ‘captain’ a small vessel.

Commodore - a temporary appointment, putting a captain in command of a squadron of ships.

Rear Admiral of the blue, white or red squadron.

An officer would begin as a Rear Admiral of the Blue, then be promoted to Rear Admiral of the White, and finally the Red.

Any captain who remained in service long enough could expect promotion to Rear Admiral, but many were not given an active role.

Progression through the admiral ranks was by seniority.

Vice Admiral of the blue, white or red.

When he died at Trafalgar, Nelson had reached the rank of Vice Admiral of the White. He’d also earned the right to be addressed as Lord Nelson, on being granted a barony following the Battle of the Nile. He’d also been made Duke of Bronte by the King of Sicily.

Admiral of the blue, white or red.

Admiral of the Fleet - a position held by between one and three people at a time. Jane Austen’s brother Francis achieved this rank in 1863.

Lord Nelson KB after a painting by AW Devis from Horatio Nelson and the Naval Supremacy of England by W Clark (1890).

Warrant Officers

A Royal Navy ship had to be largely self-sufficient for weeks, perhaps months, at a time. This meant having a crew with a wide range of skills beyond seamanship and naval warfare.

Warrant officers provided many of these skills. They included:

Master - senior warrant officer, responsible for navigation, log keeping and the ship’s anchors.

Surgeon - the senior medical officer on the ship.

Purser - responsible for managing the ship’s stores.

Chaplain - provided religious services.

Boatswain - responsible for sails, rigging and the ship’s boats.

Gunner - kept the ship’s guns in good order.

Schoolmaster - teacher to the boys aboard ship.

Carpenter

Cook

Sailmaker

A warrant officer might bring aboard knowledge and skills he’d learned before joining the Navy, such as carpentry or medicine. Others were drawn from Able Seamen who demonstrated the aptitude needed to do the job well.

Many warrant officers had assistants, drawn from the seamen and landsmen aboard.

The term ‘warrant officer’ comes from their role being established by a warrant from the Navy Board. This was a document that confirmed someone’s status in a particular role on a ship.

Petty Officers

While an Able Seaman was unlikely to become a commissioned or warrant officer, he could aspire to the status of petty officer.

Petty officers were seamen with extensive knowledge of how a ship operated, along with a wealth of experience and some degree of leadership ability.

Petty officer roles included:

Boatswain’s Mate - assistant to the Boatswain.

Quartermaster and Mates - responsible for stowing ballast and stores.

Gunner’s Mate and Quartergunners - assistants to the gunners.

Captains of the Tops - seamen in charge of different sections of the ship.

Yeoman of the Store Rooms - their duty was to protect valuable stores, including gunpowder.

Earthenware model of a seaman, about 1800. Displayed at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

Seamen and Landsmen

Most of a ship's crew were seamen or landsmen. They set and furled the sails, scrubbed the decks, loaded and unloaded stores, and carried out almost all the menial tasks needed to keep the vessel in good order and ready for action.

They also loaded and fired the cannons in battle and, if necessary, were armed to get involved in close-quarters combat.

The only qualifications to be a seaman were to be able-bodied and capable of following orders - and even these were waived from time to time.

Some landsmen were recruited for their particular skills, such as baking or coopering (making barrels).

Many others joined simply because they needed a job. Some took on tasks they were familiar with on land, such as looking after livestock. Others were general labourers. In time, some landsmen acquired the skills to be rated as seamen.

Every new recruit (whether willingly or via the press gang) was given a rating. These included:

Boys Third Class (under 15 years of age)

Boys Second Class (between 15 and 18 years of age)

Ordinary Seaman (had limited experience of working on a ship)

Able Seaman (experienced seaman)

Landsman (had no experience of working on a ship)

This rating wasn’t the same as a rank. It could go up and down, depending on the opinion of the officers in command.

Boys First Class were those who joined with the intention of becoming officers. Many Midshipmen began their career as a captain’s boy servant.

Very few seamen became sea officers. They had a better chance of becoming petty officers.

This is one sailor’s recollection on joining HMS Macedonian at Gravesend, in 1810, when aged 13:

“The crew of a man of war is divided into little communities of about eight, called messes. These eat and drink together, and are, as it were, so many families. The mess to which I was introduced, was composed of your genuine, weather-beaten, old tars.”

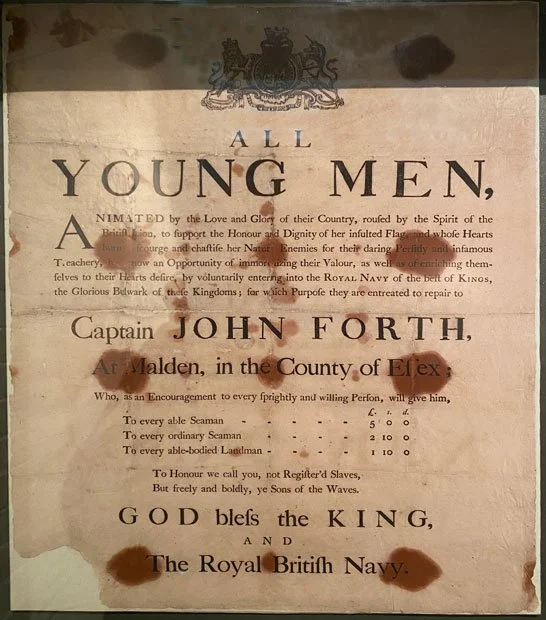

Royal Navy recruiting poster from late 18th century, displayed at National Maritime Museum, Greenwich (2022).

Marines

The Royal Marines were, and still are, soldiers based on Navy ships. Their duties included acting as guards when necessary and to lead landing parties. Marines might be called on to restore order when sailors became unruly or even mutinous.

They had their own system of ranks.

Colonel

Lieutenant Colonel

Major

Captain

Lieutenant

Sergeant

Corporal

Private

The distinction between marines and seamen is captured in this description from retired naval officer Captain Basil Hall:

No two races of men, I had well nigh said no two animals, differ from one another more completely than the ‘Jollies’ and the ‘Johnnies’.

The marines, as I have before mentioned, are enlisted for life, or for long periods, as in the regular army, and when not employed afloat, are kept in barracks, in such constant training, under the direction of their officers, that they are never released for one moment of their lives from the influence of strict discipline and habitual obedience.

The sailors, on the contrary, when their ship is paid off, are turned adrift, and so completely scattered abroad, that they generally lose, in the riotous dissipation of a few weeks, or it may be days, all they have learned of good order during the previous three or four years.

Even when both parties are placed on board ship, and the general discipline maintained in its fullest operation, the influence of regular order and exact subordination is at least twice as great over the marines, as it ever can be over the sailors.

Andrew Knowles researches and writes about the late Georgian and Regency period. He’s also a freelance writer and editor for business. He lives with his wife Rachel, co-author of this blog, in the Dorset seaside town of Weymouth.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Regency History

by Andrew & Rachel Knowles

We research and write about the late Georgian and Regency period.

Rachel also writes faith-based Regency romance with rich historical detail.

More military posts

Popular posts

Notes

Sources used include:

Fragments of Voyages and Travels by Captain Basil Hall RN (1840)

Thirty Years From Home, or A Voice from the Main Deck by Samuel Leech (1843)