Cowering in the Cockpit: The Bombardment of Algiers in 1816

Bombardment of Algiers by George Chambers

We love reading and sharing first-hand accounts of life in the Regency. Sometimes that life is relatively quiet and safe, while on other occasions it’s lively and dangerous.

This post is an example of the latter. It’s from an account written by Araham Salamé, from Egypt. He was aboard HMS Queen Charlotte, serving as interpreter to Admiral Lord Exmouth. He was present during the bombardment of Algiers on 27 August 1816.

Why the Royal Navy bombarded Algiers

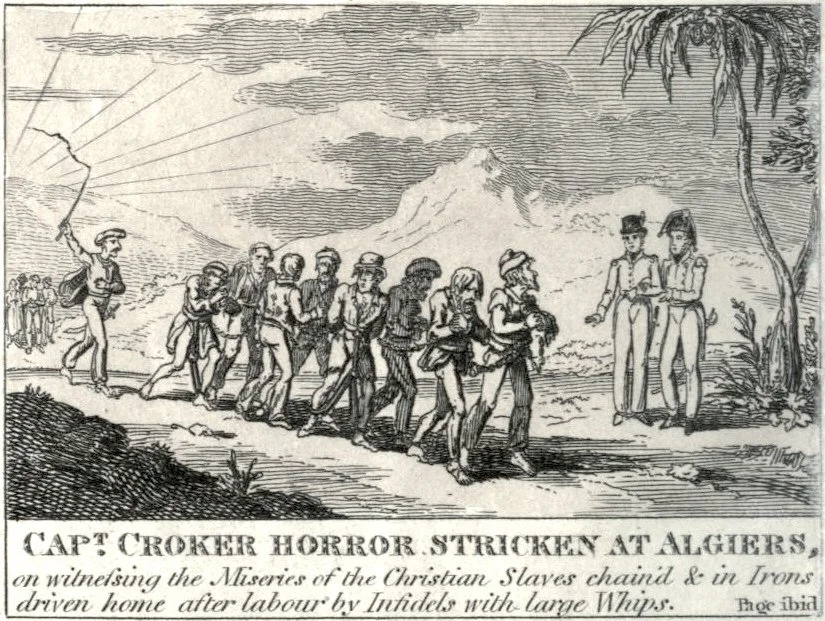

Thousands of Christians, many of whom were European, were in slavery in Algeria. Now that France was defeated, Britain was turning its attention to other threats. This included piracy along the North African coast, where many sailors had been captured.

In 1816 Admiral Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth, lead a small fleet with the intent of attack the city of Algiers.

Christian slavery at Algiers, 1816, by Cruikshank

Firing of the first shot

Algiers was an unusual battle, being fought between a Navy fleet and troops on the shore. In previous negotiations, both sides agreed not to fire the first shot but, Salamé reports: ‘At a few minutes before three, the Algerines, from the Eastern battery, fired the first shot.’ A ferocious exchange of cannon fire began.

“My ears being deafened by the roar of the guns, and finding myself in the dreadful danger of such a terrible engagement, in which I had never been before, I was quite at a loss.”

Lord Exmouth told Salamé to go below and he headed for the cockpit.

The cockpit in a sailing ship was the area used by the surgeon and his team during battle.

On his way down, Salamé ‘had the leisure to observe the management of those heavy guns of the lower deck.’

“I saw the companies of the two guns nearest the hatchway, they wanted some wadding, and began to call “wadding, wadding!” but not having it immediately, two of them swearing, took out their knives and cut off the breasts of their jackets where the buttons are, and rammed them into the guns instead of wadding.”

Wadding was material stuffed into a cannon along with the ball, to make it more efficient.

“At last I reached the cockpit; when Mr Dewar, the surgeon, Mr Frowd, the chaplain, and Mr Somerville, the purser, with some other friends, met me, and began to congratulate me on my safe return, for they never expected that I should escape.

They told me that we were pretty safe, because the cockpit was about two or three feet below the watermark, and that I had nothing to fear.”

Interpreter becomes a medical assistant

Salamé remained fearful, but writes that he came to accept that ‘every living being is uncertain of his existence.’

“And thus, I commenced assisting those poor wounded people after they were dressed; for, humanity and natural sensibility, at such a dreadful time, call upon every body to have pity, and to help the unfortunate.

It was indeed a most pitiable sight - but I think the most shocking in the world, is that of taking off arms and legs.”

Medicine was pretty basic in 1816. A ship’s surgeon might do what he could for the injured, but his resources were limited and, in battle, the numbers needing help were overwhelming.

“From curiosity, I wished to observe the Doctor’s operations. But while I was attending to the first one, which was that of taking off an arm, I could not bear it.”

Surgeons saw. This one was used at Waterloo.

The sight and sound of the bone saw was too much.

“At this time, I saw Lieutenant John Frederick Johnstone come down to the cockpit, wounded in his cheek. After he had been dressed, and remained for a short time, laughing with me, he asked me to help him put on his coat, and went to the hatchway, wishing to go on deck again; I then held him from behind by the shoulders to make him stop and said, “Where are you going? You are wounded.” In reply he said, “I am very well now, I must go.” And so he went directly.”

Two hours later the lieutenant was brought down to the cockpit again, this time ‘with his left arm taken off quite from his shoulder.’

In a footnote, Salamé tells the sorry story of the lieutenant gradually recovering on the voyage back to England, only to die shortly before landfall. He was buried at sea, just off Plymouth.

Passing the powder to feed the guns

Back in the cockpit, during the battle:

“About this time, I was sorry to see my friend Mr Grimes (his Lordship’s secretary) conducted below; he had received several wounds from splinters, and was obliged to quit the deck from loss of blood.”

As they smashed into the wooden structure of the ship, cannonballs sent sharp splinters, some of them huge, flying in all directions. They were a common cause of injury in battle.

“I began to have more courage, and jump up, now and then, to the lower deck to see what was going on; and so, for the rest of the action, I employed myself in passing the empty powder boxes to the magazine; because I found it more agreeable than attending the doctor.”

There were no passengers on a Royal Navy ship during battle. That is, everyone on board was expected to make themselves useful.

Like Salamé, most were sent to the cockpit to help the surgeon and his mates, because it was likely they were overwhelmed with the injured. In another footnote, he records that some seamen's wives helped their husbands by passing them powder and shot.

“I observed, with great astonishment, that during all the time of the battle, not one seaman appeared tired, not one lamented the dreadful continuation of the fight; but on the contrary, the longer it lasted, the more cheerfulness and pleasure were amongst them. ”

When the fighting finished the seaman in charge of gunnery, Mr Stair, told Salamé he was about 70 years old and had been in more than twenty actions, but that never heard of one that ‘consumed so great a quantity of powder as this.’

Lord Exmouth himself had remained on deck throughout the entire fight.

“It was indeed astonishing to see the coat of his Lordship, how it was all cut up by musket balls, and by grape; it was behind, as if a person had taken a pair of scissars[sic] and cut it all to pieces.”

The aftermath of Algiers

The long hours of cannon fire between ship and shore led to the death of hundreds on both sides. It also resulted in a treaty between the Dey of Algiers and the British, and the release of hundreds of slaves.

However, the Barbary slave trade continued until around 1830.

Andrew Knowles researches and writes about the late Georgian and Regency period. He’s also a freelance writer and editor for business. He lives with his wife Rachel, co-author of this blog, in the Dorset seaside town of Weymouth.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Source

A Narrative of the Expedition to Algiers in the Year 1816 by Abraham Salamé (1819).

Regency History

by Andrew & Rachel Knowles

We research and write about the late Georgian and Regency period.

Rachel also writes faith-based Regency romance with rich historical detail.