A Short Explanation of the Long S

The long s is one of the frustrations of reading printed documents from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

That said, the long s is also a delightful reminder that what I’m reading was written, and printed, over 200 years ago. However, it does cause me to occasionally stumble over unusual words.

What is a long s?

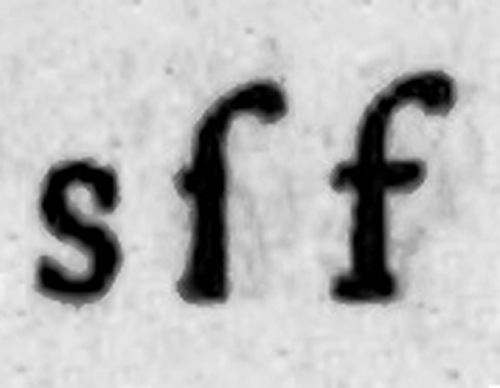

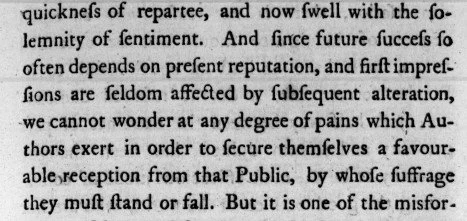

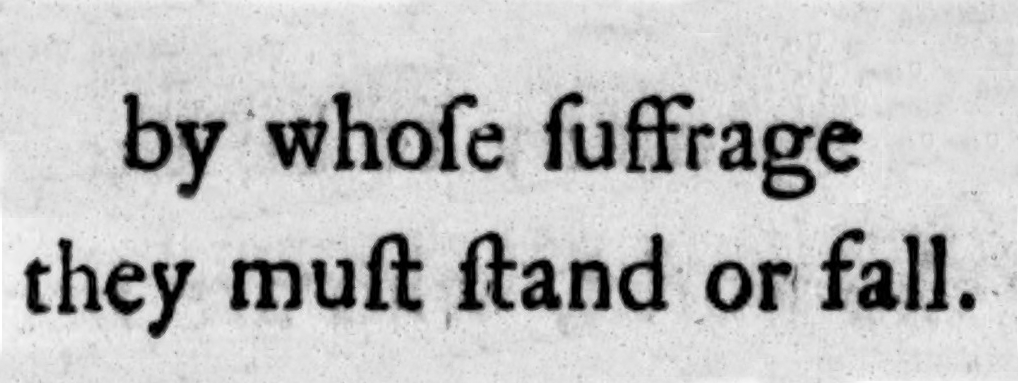

The long s is a form of the letter s, printed to look similar to a lower-case f. Here’s an example from The Loiterer, a publication by two of Jane Austen’s brothers, James and Henry.

As you can see, the long s makes an appearance in almost every line.

The origins of the long s goes back to ‘Roman cursive medials’, which probably means something to students of written language or linguistics. That’s not something I particularly want to get into.

Whatever its origins, the long s was commonly used in material printed in English until the early 1800s.

Look closely and you’ll see the long s isn’t quite the same as a lower-case f. While f has a bar crossing the upright, the long s only has one half of that bar, a stub, on the left side of the upright.

Spot the difference between a long s and a round s

The letter s we used today is referred to as the round s.

How the long s was used

How did a writer or printer decide when to use the long s or a round s? It probably came down to their preference, which was in turn influenced by books such as The Printer’s Grammar (1755) by John Smith. This went into considerable detail about the use of the long s.

In general, you’ll find the long s being used:

In words starting with a lower-case s.

Where s is repeated, it’s the first s.

Not at the end of a word.

The long s was also used in handwriting.

The end of the long s

By the early nineteenth century the long s was falling out of use. The 1808 edition of The Printer’s Grammar refers to the round s as being generally adopted, with makers of type no longer including the long s in their fonts.

The life of the long s was extended, by some, in their handwriting. It seems that Victorian authors Charlotte Bronte and Wilkie Collins both continued to employ the long s in their letters and manuscripts.

How I was caught out by the long s

As I indicated at the start of this short article, the long s retains the capacity to confuse the reader who’s not prepared for it.

This happened to me just recently, as I was reading a list of business owners in the town of Alton, Hampshire, in the early 1800s. One was a manufacturer of something called fergedenin.

What is (or was) fergedenin? Google gave me no answers, so I asked the question in our Regency History newsletter. One reader came back suggesting that I replace the long s with a round one.

Of course! The word wasn’t fergedenin, it was sergedenin. Serge is a fabric, and denin suggests something akin to denim. This made sense, as other items made by the business were textiles.

If, like me, you read documents from the late eighteenth century, don’t get frustrated by the frequent use of the long s. Yes, it makes you work a little harder as you read, but at least most of the words are recognisable.

It makes me glad I chose to study this era and not, say, the early medieval period, which was where I began at university.

Andrew Knowles researches and writes about the late Georgian and Regency period. He’s also a freelance writer and editor for business. He lives with his wife Rachel, co-author of this blog, in the Dorset seaside town of Weymouth.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Regency History

by Andrew & Rachel Knowles

We research and write about the late Georgian and Regency period.

Rachel also writes faith-based Regency romance with rich historical detail.