Fanny Burney’s Secret Work: Evelina

Fanny Burney from Diary and letters of Madame D'Arblay (1846)

In a fit of fear about what others might think of her writing, fifteen-year-old Fanny Burney burned the manuscript of the novel she’d written.

But a writer’s pen is soon picked up again. She began to write the sequel to her first, tragic, tale.

A little over ten years later, she was thrilled to see that novel being read by friends and family. But her fears remained and she arranged for the book to be published anonymously.

Evelina, or the History of a Young Lady’s Entrance into the World appeared in print in January 1778. The title page gave no clue as to the author. Unlike other anonymous novels by women, it did not even say ‘By a Lady’.

Even the publisher, Mr Lowndes, was unsure of the book’s author. He thought it to be a gentleman ‘from the other side of town’.

What Lowndes had spotted was the book’s potential. It became a bestseller of its day.

Writing and publishing in secret

Fanny wrote Evelina in her late teens and early twenties. Her writing time was in the secret spaces of the day, when her father, Charles Burney, would not notice.

Charles Burney was a highly respected music teacher and historian. He worked long days, giving lessons and researching for his grand project, A General History of Music.

Fanny was kept busy working as his assistant. Her job was to copy his manuscripts in preparation for publication. As she watched how her father turned his writing into printed pages, she must have learned the business of publishing.

Fortunately for us, Fanny kept a detailed journal for much of her life. In it she confides how difficult it was to find time to write.

Evelina is a novel of more than 100,000 words. Imagine writing that up in draft, then editing, and then writing it out neatly for the publisher. It’s many hours of work.

On top of that, she did not dare complete the final manuscript in her usual handwriting. She wanted to remain anonymous, but because of the work done for her father, London publishers were familiar with her writing, so she had to adopt a different hand.

We know so much about how Fanny wrote Evelina because for many years she kept a detailed journal. Here she confides to it how difficult it was to find time to work on her project.

The fear of discovery, or of suspicion in the house, made the copying extremely laborious to me; for in the day time, I could only take odd moments, so that I was obliged to sit up the greatest part of many nights, in order to get it ready.

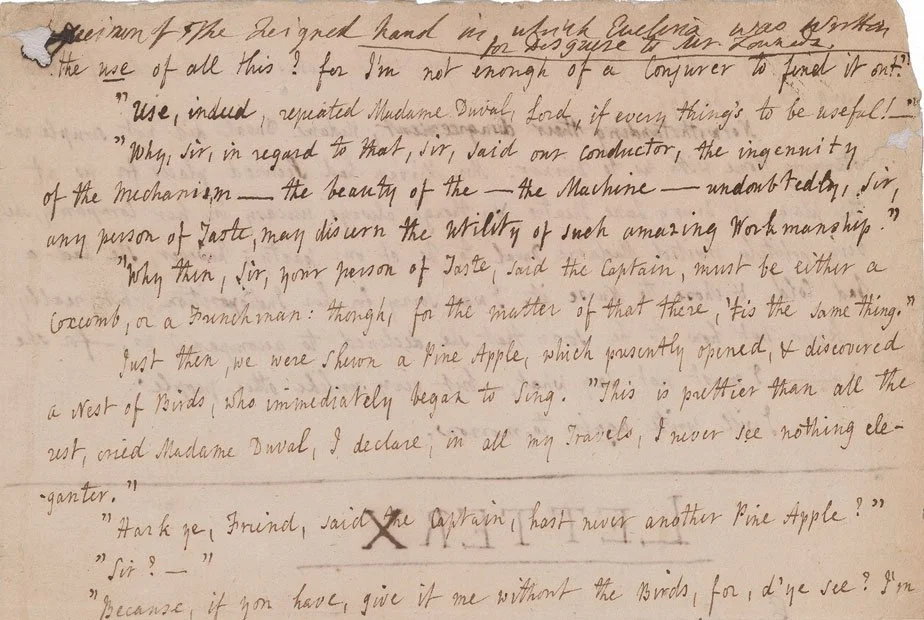

Possibly the only surviving page of Evelina manuscript in Fanny’s feigned handwriting.

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

A secret among siblings

Fanny’s writing wasn’t kept secret from everyone. She shared it with her closest sister, Susan. Her younger brother, Charles, was also in on it. He played a vital role in getting it into print.

While she was shy about sharing her writing with her father, Fanny was also uncomfortable keeping the secret from him. She let him know she was approaching publishers and he approved. But, being so focused on his own work, he enquired no further. Even when he read Evelina, he had no idea his daughter was the author.

The next challenge was to find a publisher, and to negotiate a deal without Fanny giving away her identity. Her younger brother, Charles, aged about 20, was selected as courier.

An unfinished version of the manuscript was conveyed to publishers. The first that Charles took it to refused to handle anonymous work. The sisters and brother then decided to send it to Thomas Lowndes.

Again, Charles was the courier. Lowndes expressed interest, but would only take it as a finished work. Fanny set to work completing the manuscript.

To add to the air of mystery around the author, Lowndes could only communicate with Fanny by sending messages addressed to a Mr Grafton at the Orange Coffee House.

Evelina interrupts Mr Macartney

from Evelina Vol 2 (1808 edition)

Surprises for Fanny

In late January 1778 Fanny’s stepmother read out an advertisement from the newspaper, for a newly published book that had caught her eye. It was titled: Evelina.

That was Fanny’s first surprise. She didn’t know the book had gone to press.

Her second surprise was that the publisher agreed to pay £20 for her manuscript.

An offer which was accepted with alacrity, and boundless surprise at its magnificence!

Fanny’s delight at being offered such a sum for her book probably did not last very long. For a young woman with no independent means it may have sounded like a fortune.

But her father, when he found out she was the author, thought differently. In a letter from her sister to Fanny, he’s reported as saying:

It really appears to me that Lowndes has had a devilish good bargain of it—for the book will sell—it has real merit.’

For her next book, Cecilia, published four years later, she was paid £250. The next one after that, Camilla, earned her a fee of £1,000.

Fanny’s final surprise was the ‘exceeding odd sensation’ that came from knowing:

that a work which was so lately lodged, in all privacy in my bureau, may now be seen by every butcher and baker, cobbler and tinker, throughout the three kingdoms, for the small tribute of three pence.

The secret gets out

For some months Fanny enjoyed seeing family and acquaintances read and enjoy Evelina, and then speculate on who the author might be.

Charles Burney, and many others, held up Evelina as some of the finest literature of the day. Six months after it was published, he discovered the author to be his daughter.

We don’t know how the secret was revealed. But he seemed keen to tell his friend Hester Thrale, at whose grand house he was a regular visitor. Charles was employed to teach music to the Thrales’ eldest child, and was often invited to stay for dinner.

Speculation as to the author was increasing. Sir Joshua Reynolds, the artist, stayed up all night to read the book and, according to Fanny’s journal: ‘vows he would give fifty pounds to know the author!’

She was curious as to how the publisher, Thomas Lowndes, handled enquiries about the book’s authorship. She went to see him, but nervous she might give away her secret, she took her mother along to ask the question.

She asked if he could tell her who wrote it.

"No," he answered; "I don't know myself."

"Pho, pho," said she, "you mayn't choose to tell, but you must know."

"I don't indeed, ma'am," answered he; "I have no honour in keeping the secret, for I have never been trusted. All I know of the matter is, that it is a gentleman of the other end of the town."

Once Hester Thrale knew Fanny to be the author, she was invited to dine at their house in Streatham. Fanny became a regular visitor and met well-known figures of the age, such as Samuel Johnson, Sir Joshua Reynolds and Elizabeth Montagu.

By late 1778 Fanny’s family, friends and acquaintances knew she was the author of Evelina. But she wasn’t prepared for it to become fully public knowledge. Hence her strong reaction when, that autumn, the secret was revealed in an essay by George Huddesford.

I cannot tell you, and if I could you would perhaps not believe me, how greatly I was shocked, mortified, grieved, and confounded at this intelligence: I had always dreaded as a real evil my name's getting into print - but to be lugged into a pamphlet!

It was only a passing mention in a satirical publication addressed to Sir Joshua Reynolds. The reveal only occurred in a footnote.

Or gain approbation from dear little Burney*?

* The Authoress of Evelina.

For a while Fanny was upset that a close friend had given away the secret. The phrase ‘little Burney’ was used at the Thrales, particularly by Samuel Johnson.

However it occurred, Fanny’s name was now associated with one of the most popular novels of the time.

If you want to know more about the story of Evelina, but haven't got time to read a novel of 100,000 words, Rachel has written a summary here.

Andrew Knowles researches and writes about the late Georgian and Regency period. He’s also a freelance writer and editor for business. He lives with his wife Rachel, co-author of this blog, in the Dorset seaside town of Weymouth.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Sources used include:

Diary and Letters of Madame D'Arblay. Vol 1 edited by Charlotte Barrett, 1842

The Early Diary of Frances Burney Vol 2

Warley: a satire, Part 2, by George Huddesford, 1778

Regency History

by Andrew & Rachel Knowles

We research and write about the late Georgian and Regency period.

Rachel also writes faith-based Regency romance with rich historical detail.