Josiah Wedgwood: Pioneering Potter and Philanthropist

Josiah Wedgwood, painted by George Stubbs

No grand Georgian house is complete without a display of Wedgwood ceramics on at least one mantelpiece. How is it that the work of one man has become the style associated with the elegant lifestyle of the wealthy in late Georgian and Regency Britain?

Early life of Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood was born in the summer of 1730 in Burslem, part of the region in the heart of England known as ‘The Potteries’. Today Burslem forms part of Stoke-on-Trent, which calls itself the ‘World Capital of Ceramics’.

Josiah was born into a family of potters, who owned the Churchyard Works in Burslem. He was educated at a private school until aged about 9, when he began learning how to be a thrower in the pottery. In 1744, aged 14, he began a formal five-year apprenticeship to his older brother, Thomas, who was now owner of the Works.

Thomas was unwilling to entertain Josiah’s desire to improve the family business, so the younger brother went to work for other pottery firms. His interest in experimentation seems to have been a problem for business owners reluctant to change, but his talent was recognised by Thomas Whieldon.

Whieldon ran the most successful pottery business in the area, and perhaps the country. He employed some of the most well-known craftsmen in the trade, including Josiah Spode. Despite his prominence in the industry, Whieldon’s business was losing ground to competitors. In 1754, he went into partnership with Josiah Wedgwood.

Josiah was meticulous in keeping records of his experiments

This arrangement allowed Josiah to continue experimenting. He was meticulous in recording how his experiments went, and has left us a wealth of detailed information. He was also a keen student of business and recorded the state of the trade.

In 1759, as his five-year partnership was coming to a close, he began a new series of experiments, with a view to introducing innovations through his own business.

This suite of experiments was begun at Fenton Hall, in the parish of Stoke-upon-Trent, about the beginning of the year 1759, in my partnership with Mr Whieldon, for the improvement of our manufacture of earthenware, which at that time stood in great need of it—the demand for our goods decreasing daily, and the trade being universally complained of as being bad and in a declining condition.

Wedgwood becomes Potter to the Queen

In 1760, free of his partnership, Josiah pressed on with his own business, which he established in the Ivy House Works, in Burslem. This was the first site that produced wares that can specifically be referred to as Wedgwood. They included pineapple ware and other items with fruit or vegetable decoration.

By now, Josiah was both a master potter and an astute businessman. In the early 1760s he was asked to supply a creamware tea set for Queen Charlotte and, aware of the marketing potential, he included samples of other wares. The tactic paid off, leading to more orders and his naming a range of his products as Queen’s Ware. The words ‘Potter to Her Majesty’ began to appear on his stationery.

Examples of Queen’s ware from the 1760s and 1770s.

Achieving a consistent colour for creamware was a major ambition for potters of the day. Wedgwood conducted nearly 5,000 trials to achieve the colour and finish he was happy with.

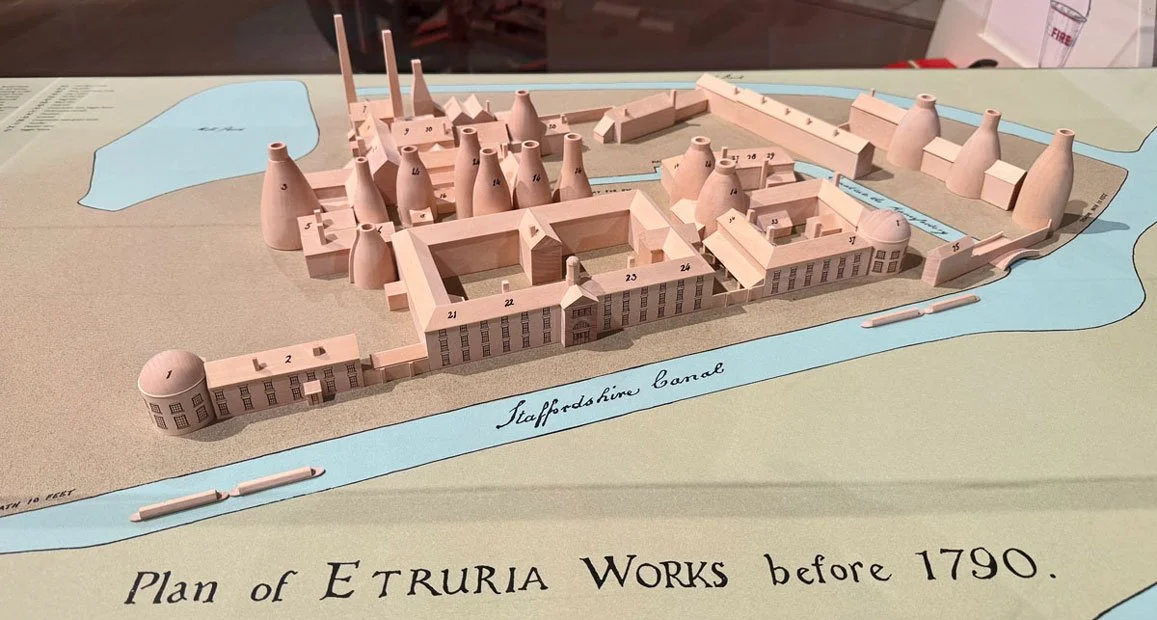

The popularity of Josiah’s products led to him opening premises in London in the mid-1760s. His ambition was to be ‘Vase Maker General to the Universe’ and, to help him achieve this, he opened a new factory, Etruria, in 1769. He also built a grand home, Etruria Hall, for himself, his wife Sarah (they married in 1764) and his growing family.

The factory and house were close to what is now the Trent and Mersey Canal. In July 1766, Josiah cut the first sod in a ceremony to mark commencement of construction.

Model of the Etruria Works, displayed at the World of Wedgwood

Despite all the success, Josiah faced personal challenges. In particular, in the late 1760s he lost a leg—amputated because of ongoing issues related to having smallpox as a child.

By 1770, Josiah had achieved his ambition of providing pottery to the world. Or at least to senior representatives of major nations. One such customer was the Empress of Russia, who ordered a dinner service. In a letter about the decoration, featuring unique views of English landscapes, Josiah wrote:

I have no idea of this service being got up in less than two or three years if the Landskips & buildings are to be tolerably done, so as to do any credit to us, & to be copied from pictures of real buildings & situations—nor of it being afforded for less than £1,000 or £1,500—Why all the Gardens in England will scarcely furnish subjects sufficient for this sett, every piece having a different subject.

It was about five years between the set of 952 items being commissioned and delivered, and it cost the Empress £3,500.

Jasperware and Wedgwood blue

Prosperity and fame did nothing to blunt Josiah’s drive to experiment and innovate. During the 1770s he refined and began to sell what we now consider to be classic Wedgwood ceramics, with white decoration on a pale blue background—known as Jasperware.

Keen to stay ahead of his competitors, Josiah ensured that the formula for creating Jasperware remained a secret. Such was his success in keeping that secret, and in marketing his products, that Wedgwood blue is now instantly recognisable almost everywhere.

Many of the designs used by Josiah were inspired by Greek and Roman classical art. One of his most outstanding creations was his replica of the Portland Vase, a rare survivor of Roman cameo glass that’s now in the British Museum. He put his first copies on exhibition in his London showroom, and it was so popular that tickets were issued to control the number of viewers.

Josiah wrote that the vase was:

The finest & most perfect I have ever made, and which I have since presented to the British Museum.

Wedgwood the philanthropist

While ambitious for his business, Josiah was also mindful of those less fortunate than himself.

He’s well known as a promoter of the abolition of slavery, creating an anti-slavery medallion in 1787. He built cottages for his workers, with nearly 100 erected by the time he died in 1795.

Josiah was deeply interested in the ideas of self-improvement, education and liberty. He supported schools and other educational institutions.

He spent a lot of time with leading thinkers of his day, particularly as part of the Lunar Society of Birmingham. This included:

Matthew Boulton (engineer)

Erasmus Darwin (physician, philosopher and grandfather of Charles Darwin)

Richard Lovell Edgeworth (inventor and educationalist)

James Watt (engineer)

Death and successors

Josiah died in January 1795, aged 64, and is buried in Stoke Minster. He and Sarah had eight children, six of whom survived him.

His eldest child, Susannah, married Robert Darwin and became the mother of naturalist Charles Darwin. His second surviving son, also Josiah, became the father of Emma Wedgwood, who later married her cousin, Charles Darwin.

The Wedgwood business was run as a partnership between Josiah’s sons, Josiah II and John, and a nephew, Thomas Byerley. In the early 1800s, Josiah II became the sole owner.

Business suffered because the wars with France disrupted trade until 1815.

In 1811, Wedgwood closed its shop in Dublin. An advertisement in Saunder’s News-Letter in Dublin reads:

Josiah Wedgwood respectfully informs the Public, that the sale of stock of Earthenware, at reduced prices, for the purpose of closing the Concern, continues this, and every day, at No. 36, Upper Sackville-street.

The business will be carried on as usual at Etruria, Staffordshire, and in York-street, St James's, London, where the utmost attention will be paid to the orders with which he may be honoured. Dublin, Jan.3, 1811.

Wedgwood continued to operate its York Street showroom in London until 1829. Decline in trade led to a sale of stock ‘at extremely reduced prices’, as well as models and moulds.

Andrew Knowles researches and writes about the late Georgian and Regency period. He’s also a freelance writer and editor for business. He lives with his wife Rachel, co-author of this blog, in the Dorset seaside town of Weymouth.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Sources include:

World of Wedgwood V&A Collection, Staffordshire

Wedgwood by Wolf Mankowitz (1953)

Wedgwood an Introduction V&A website

The Borough of Stock on Trent by John Ward (1843)

Saunder’s News-Letter, January 1811

The Morning Herald, June 1829.

Regency History

by Andrew & Rachel Knowles

We research and write about the late Georgian and Regency period.

Rachel also writes faith-based Regency romance with rich historical detail.