|

| Brighton Pavilion - the Steyne front |

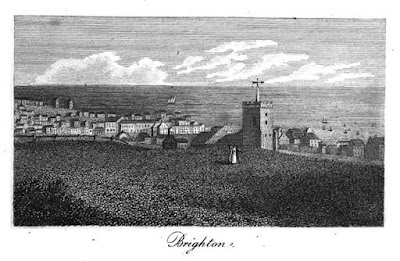

George IV's Royal Pavilion, Brighton

George IV delighted in redesigning and developing his royal residences. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the Royal Pavilion, Brighton. During the first phase of royal occupancy, the original farmhouse was converted into the Marine Pavilion by Henry Holland, but George soon tired of its Neo-classical perfections and commissioned the orientalising of the interiors.

The new stable block

In 1803, George engaged William Porden to build a new stable block. His Indian-influenced design incorporated a huge glazed iron roof based on the domed trading floor of Bélanger’s Halle au Blé and cost £49,871 to build. A contemporary guidebook described it as a “truly magnificent building”.

The Indian influence

However, the new stables and riding school dwarfed the main building, and George was soon seeking new designs for the pavilion itself which would be compatible with their magnificence. Although temporarily halted by lack of funds, in 1815 George was finally able to commission John Nash, his new favourite, to redevelop the pavilion using the picturesque qualities of Indian architecture.

The skyline of the new pavilion

Nash added two square blocks, one at each end of Holland’s Marine Pavilion, crowning each of them with a tent-like roof. In the centre, above Holland’s rotunda, Nash placed a huge onion-shaped dome, and he echoed this feature by adorning the roofs of the adjacent wings with smaller versions of this dome. The concave nature of the tent-like roofs balanced the convex shape of the onion-shaped domes, and, together with the tall Islamic minarets and chimney stacks, cleverly gave height to the long, low profile of the pavilion.

|

| The miniature onion-shaped domes and tall chimney stacks on the eastern front of the Brighton Pavilion |

Nash is recorded as borrowing Thomas and William Daniell’s “Oriental Scenery” from the prince’s library and he used inspiration from these pictures of genuine Indian buildings for some of the details of his designs.

One such element was the perforated stone screen based on the Indian “jali”, designed to provide shade and ventilation in the heat of the Indian summer. This was made from Bath stone and was situated between the tall Indian pillars which masked the saloon, music room and banqueting room. The rest of the walls were covered in stucco.

|

| The pierced stone "jali", Brighton Pavilion |

The music room

Nash’s pavilion boasted two exceptional new rooms. The first of these was the music room, which was situated in the new square block to the north with an additional extension for the largest English-made organ of the time. The room was decorated in a the Chinese style with a dramatic colour scheme of “Carmine, Lake, Crome Yellow and other expensive colours”, and a huge marble and ormolu chimney piece, made by Westmacott and Vulliamy which alone cost £1,684.

|

| The music room with its tent-like roof, Brighton Pavilion |

The banqueting room

The banqueting room, to the south, was equally magnificent, with its decorative scheme by Robert Jones. The forty-five foot high dome was painted as if it was open to a tropical sky and was almost completely filled by the representation of a huge plantain tree. From its centre, an enormous dragon was suspended, which held a thirty foot high chandelier in its claws. The chandelier alone cost over £5,600.

Four lotus-leaf bowls also hung from the ceiling, suspended by “Fum” or “F’eng” – Chinese mythological birds. The furniture included two “very large and superbly decorated Sideboards”.

Even the Princess Lieven was overwhelmed, declaring: “I do not believe that, since the days of Heliogabalus, there has been such magnificence and such luxury.”

Sources used include:

Editor of the Picture of London, A Guide to all the Watering and Sea-Bathing Places (1815)

Huish, Robert, Memoirs of George IV (1830)

Morley, John, The Royal Pavilion, Brighton

Nash, John, Views of the Royal Pavilion with commentary by Gervase Jackson-Stops (1991)

Parissien, Steven, George IV, The Grand Entertainment (2001)

Photographs © Andrew Knowles - www.flickr.com/photos/dragontomato