|

The Newspaper by Thomas Rowlandson (1808)

|

In Regency England news was

passed by word of mouth, by private letter and in the newspapers. This meant

newspapers were highly prized as a source of printed information.

As today, a wide variety of

newspapers were published. Most were distributed locally, although some found

their way across the country and even abroad. Copies were passed from reader to

reader, each of whom would avidly devour the contents even if it was a few

months old.

Newspapers are an excellent

resource for historians and writers wanting to learn more about the late

Georgian and Regency era. They offer a wealth of detail about the period, from

stories of international events through to snippets of insight into everyday

life.

Not all newspapers have

survived, and it must be remembered that then, as now, they weren’t always

reliable. A number of well-known Regency personalities were amused to hear

their deaths being reported as facts.

Three Regency

newspapers compared

I thought it would be an

interesting exercise to compare three Regency newspapers, all published on the

same day. I decided to take one from London, one from a fashionable resort and

one from a more distant part of the country—in this case, Scotland.

The papers are:

●

London Courier and Evening Gazette

●

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette

●

Perthshire Courier

I selected the 7 February 1811,

the day after the Prince of Wales was sworn in as Prince Regent, following the

passing of the Regency Act.

|

George, Prince Regent, by Sir Thomas Lawrence

c1814 © National Portrait Gallery |

Differences

between Regency and modern newspapers

Regency newspapers look unfamiliar

to the modern eye. They lack bold headlines, have very few images, and news

stories often flow in quick succession with little separation.

Pictures didn’t regularly

appear in newspapers until the 1830s. There are three tiny illustrations in the

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, but none are representations of news

stories.

The front page of the newspaper

is mostly advertisements and notices. While each newspaper does have some

marked sections (such as ‘Naval Intelligence’), there’s a sense that much of

the content was added as it arrived.

Consistent

features between all three newspapers

Reading one Regency newspaper

is fascinating. Looking at three in close succession reveals some distinct

similarities between them.

All three newspapers relied

heavily on other publications and letters as the source of their material, and

they revealed these sources. There’s little of what we could consider to be

journalism.

Both the London and Perthshire

newspapers gave considerable space to the Regency, which came into effect on 5

February 1811, two days before publication. The Perthshire news only went up to

1 February. There’s no surprise it was behind the London papers, given that

it’s over 400 miles north of the capital city.

All three newspapers give space

to announce births, deaths and marriages. There are no announcements of

engagements or betrothals. I’m unsure when it became the fashion to announce

these, but I’ve never seen examples in Regency newspapers.

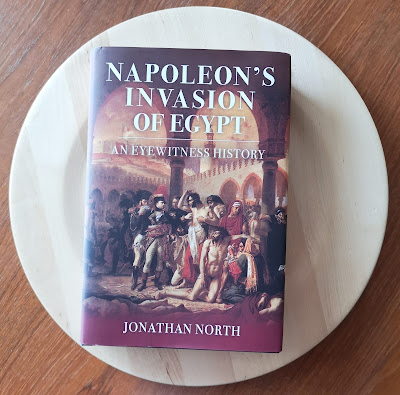

The state lottery features in

the Bath and Perthshire newspapers, with an identical announcement headlined

‘The Regent’s Procession’. The next line follows on from the heading:

...is at

this crisis interesting to the country; and this memento is at this time

interesting to ourselves: for if the New Administration adopt the expected new

measures, there will be No More LOTTERIES; therefore the ONLY opportunity we

may ever have to gain an independent Fortune by the risk of a small Sum of

Money, is the Present STATE LOTTERY.

The lottery is also advertised

in the London newspaper, but without the announcement.

|

Lottery Drawing, Coopers Hall

from The Microcosm of London Vol 2 (1808-10) |

Read another

Regency newspaper for free

All three newspapers I’ve

mentioned here are in The British Newspaper Archive, an online resource

containing hundreds of papers. Many are protected by copyright, meaning you

need a subscription to get access and you can’t publish screenshots.

All three papers I’ve chosen

are copyright protected (links in the notes below). However, you can read other papers from 7 February

1811 for free, because they are not subject to copyright.

You can open a free account at

The British Newspaper Archive and read papers such as The General

Evening Post.

Newspapers that can be read for

free are marked as being in the Public Domain. However, you still can’t publish

screenshots because the photos of the newspapers are also copyright protected.

Stories that caught my eye

From London Courier and Evening Gazette

An advertisement: NERVOUS

DISORDERS - Doctor FOTHERGILL’s NERVOUS CORDIAL DROPS have been the happy means

of restoring thousands from the following Disorders: Lowness and Nervous

Affections, Consumption, Hypochonoriaism, Hysterics, Spasms, Palsy, Apoplexy,

Loss of Appetite, Bilious Complaints, Convulsions and Fits attending Pregnancy

proceeding from a disordered state of the Stomach, and Indigestion accompanied

by Sick Head aches, Heartburns, &c &c.

From Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette

A curate of a parish in Sussex

was, on Friday, committed to the county gaol, under the charges of writing a

threatening incendiary letter to Mr R Jenner, of Maresfield, and of setting

fire to his house, with the view of defrauding the Union Fire-Office.

From the Perthshire Courier

Thursday, a young man, a

wright, having failed in an attempt to split a piece of hard wood, blew it up

with gun-powder; but unfortunately was struck with so much violence by the

splinters, on the head and breast, as to occasion his death the next morning.

A fun insight into how the newspapers collected some of

their news (or in this case, didn’t):

We are obliged to our “Reader,” in Dunkeld, for his desire

to acquaint us with the transactions of his neighbourhood. He should however,

have subscribed his letter, that we might thus have been more able to

conjecture, whether it was the wish of the parties to have their names, offices

and success in the “Curling Match,” communicated to the public. He should also

have paid the postage.

|

A Man of Fashion's Journal by Thomas Rowlandson (1802)

|

A summary of each newspaper

London Courier and

Evening Gazette

This is a 4-page newspaper. The

first page header reads ‘The Courier’, dated Thursday February 7, 1811. It’s

issue number 4,911 and the price is six pence halfpenny.

This was a daily newspaper.

The four pages are dense with

text, arranged into four columns of equal width.

Page 1

Articles about an intended

canal, an appeal to support British prisoners of war in France and a mix of

advertisements ranging from the state lottery to sale of cucumber seeds.

What we would consider to be

the headline item, top left of the page, is about a meeting to object to a

proposed canal in a town more than 80 miles from London. There is no headline

to inform the reader what the piece is about. The article reads as minutes of a

meeting.

Page 2

There’s much more news on this

page, opening with information about Spain and Portugal. These were areas of

interest because of the Peninsular War being fought against the French. Much of

the information is cited as coming from Spanish newspapers and private letters.

The second two columns of this

page deal with events in the British parliament. There’s a detailed report of

the ceremony of installation for the Prince Regent, which occurred the day

before.

Page 3

Information about the

installation continues, along with a bulletin headlined ‘The King’. It simply

reads: ‘Windsor Castle Feb 7, His Majesty seems to be making gradual progress

towards recovery.’

This is followed by a number of

short items relating to the war. Again, these are drawn from other sources,

such as letters and other newspapers. The page continues with political news

and opinion.

The final column is headed

‘Naval Intelligence’. It includes more information about the war, and ends with

the story of a man stealing from various hotels.

Page 4

Unlike modern newspapers, sport

does not occupy the back pages. The varied mix of content continues, with

political and legal news. These are followed by announcements of births,

marriages and deaths, and then more advertisements.

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette

This is also a 4-page

newspaper. The first page header reads ‘The Bath Chronicle’, dated Thursday

February 7, 1811. It’s issue number 2,554 in volume 54, and the price is six

pence halfpenny. There’s a detail that the price is broken into Stamp Duty of

three and a half pence, with paper and print being what looks like 8C.

The four pages comprise five

columns of text. There are a couple of small illustrations—effectively logos—at

the top of advertisements.

Page 1

The first column is headlined

as ‘Friday and Saturday’s Posts’, indicating that it’s news from London, from

about a week earlier. This news, in turn, opens with items from American

newspapers from late January.

The opening news items are

followed by a host of adverts and public notices, including the ‘Rates for

Carrying Soldiers’ Baggage’.

Page 2

This follows a similar pattern

to page 1, being headlined ‘Sunday and Tuesday’s Posts’. This is a mix of items

about the war, a summary of the short bulletins about the King’s health, and

about politics in the light of the new Regency.

There’s a note about ‘Ladies

fashions for February’ and notice of a marriage and a death. A section headed

‘Market Chronicle’ gives prices for grain, flour, hops and other goods.

The rest of the page is given

over to more advertisements and notices.

Page 3

Yet more news gleaned from

London newspapers, more marriages, births and deaths, notices of concerts and

plays in Bath, and—the most essential item for the fashionable—a list of the

recently arrived in the city. Yet more advertisements.

Curiously, a short section on

horse races opens: ‘Nothing can be more dull and unedifying than the accounts

of sports and pastimes of the present day.’

Page 4

This opens with political news,

then it’s back to military updates and sundry other news items. Yet more

births, marriages and deaths, and a list of bankruptcies. This back page

concludes with another couple of columns filled with advertisements.

Perthshire Courier

Again, this newspaper covers 4

pages. The first page header reads ‘Perth Courier’, dated Thursday February 7,

1811. It’s issue number 157, and the price is sixpence.

It seems to have been a weekly

newspaper, published on a Thursday.

The four pages comprise five

columns of text. Unlike the other two papers, the front page has a headline

that stands out: ‘The Regent’s Procession’, which I mentioned above.

Page 1

The government or state lottery

features heavily at the top of this page, with two advertisements from brokers

promoting the lottery. The rest of the page is given over to adverts and

notices.

Page 2

This page is packed with news.

It’s headed ‘Foreign Intelligence’ and comprises extracts from official

dispatches and private letters relating to the Peninsular War in Spain and

Portugal. There’s a short section about America and Mexico.

Under ‘Domestic Intelligence’

it shares information from the London Gazette, from late January. There’s a

section on the average prices of British corn, then a report from the ‘Imperial

Parliament’ about the Regency Bill, dated 28 January.

Page 3

The Regency Bill discussions in

Parliament take up half of this page, following its progress until 1 February.

There’s a section on the health of King George III and further discussion about

the Regency.

All this is followed by short

news items about deaths and a shoplifting incident in London. The page ends

with various news items from the Royal Navy.

Page 4

This page includes news from

Scotland and Perth—typically short reports about crimes or unfortunate deaths.

A reasonable number of births, marriages and deaths are listed.

The page concludes with more

notices, prices of grain and other commodities, and finally the ‘State of the barometer and thermometer

taken at nine o’clock morning’ each day. This tells us that for the last week,

it’s been cold with snow and rain.

Rachel Knowles writes faith-based Regency romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew, who wrote this blog.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Note:

All three newspapers are

available to read if you subscribe to The British Newspaper Archive.

You can find the copies I looked

at here:

London Courier and Evening Gazette

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette

Perthshire Courier

.jpg)