|

| Detail from Merton College, Oxford: a marriage ceremony in the chapel by J Bluck (1813) after AC Pugin Wellcome Collection used under Creative Commons Licence (CC BY 4.0) |

If a young lady or gentleman wanted to get married in Regency England while they were a minor, that is before they came ‘of age’, they needed the permission of their parent or guardian.

When did a Regency person come ‘of age’?

The age of majority during the Regency was 21 years old. It was only reduced to the age of 18 relatively recently, in 1970.

Was parental permission always necessary?

Parental permission for the marriage of minors was required for all weddings in England except where the underage party had been married before.

Marriage by licence

To obtain either a common marriage licence or a special licence for the marriage of underage persons, permission was required from a parent or guardian of each underage person. Either party to the wedding or a third party had to give a sworn statement that this permission had been given before the licence could be granted.

If they lied about having parental consent, the marriage could be set aside.

Marriage by banns

|

| The dance of death: the wedding by T Rowlandson (1816) Wellcome Collection Used under Creative Commons Licence (CC BY 4.0) |

It would appear, however, that some unscrupulous persons tried to ignore this if it was in their interests to do so.

Ackermann’s Repository (January 1815) reported the sad case of Elizabeth Chandler, the daughter of a respectable tradesman:

Four years since, I became acquainted with John P –; we walked out together, we sat next to each other at every holiday meeting, and, in short, I soon began to have a particular affection for him; and as he was constantly at our house, I always treated him as the man who would become one day my loving husband. This, sir, at length was realized, and this day month I uttered the vow, which he also pronounced at the same altar, to cherish each other till death should us part.For a whole fortnight did we live, at least if I may judge of his feelings by my own, as happy as sincere love could make us: at the end of this period, however, I began to endure what I have ever since felt, the torments of love unreturned, and a character blasted for ever.After the short moments of a fortnight’s joy, he left me, as he said, but for a day, nor could I have believed it to be in the nature of man to be so perjured, if he at that time mean ever to return again. For three days, agony, suspense, and dread racked my frame. I wrote, I followed to the place whither he intended to go: alas! He was denied to me, and though fainting at the door, from the opprobrious terms his friends lavished on me, he came not to comfort her, who had, for him, given up what she supposed the rites of the church had warranted.1

Elizabeth’s husband wrote her a letter, telling her:

I have left you then for ever, for my friends insist upon it, that I must see you no more. My uncle Palmer, on whom you know I depend, has declared, unless our match be set on one aside, he will never see me no more; and you know, you have no fortune, and, if you love me, you cannot wish I should starve. It appears, although I did not know it myself, that I am six months under age, and I find, by the law of the land, I cannot marry. If, however, you should have a child, we will maintain it. I am very sorry, but what can I do? They have sent me to a place which I must not tell you of. In hopes you will bear this with becoming fortitude, I take my leave of you forever. So no more at present from your once loving husband, John P –.2

Elizabeth was distraught and wrote:

His cruel parents are determined to part us, and my poor incensed and less powerful parents can only mingle their tears with mine. They say the bans thrice put up, the solemnization in every particular, will avail me nothing; my husband being a minor is yet no husband to me – wretched, wretched girl!3

The writer of the article, Scriblerus, was deeply moved.

I conjure, therefore, the legal correspondents of the Repository, to exert themselves in behalf of this, perhaps not the last instance of female credulity and male baseness; and through the medium of the next number, point out some remedy to restore an unfortunate female to her peace of mind and respectability of character.4

The following issue published a story of Mary F – r, a lady who had married an underage man after banns who wished to get out of her marriage because of her ‘husband’s cruelty, and infamous behaviour of every description.’5

This woman wrote:

I was told, and am still told, that his being a minor will avail me nothing, as the bans were regularly put up. If what the unfortunate Elizabeth states be the fact, in the broad meaning of the assertion, surely I could as well take advantage of my husband’s minority, as in her case the husband or his friends could. Surely a man ought not to be allowed to take advantage of his own wrong-doings, to leave an innocent and injured woman; when, if that woman wished to do so, from his cruelties or other bad behaviour, she should be shut out from the same remedy.6

In April, Scriblerus published a response:

Johannes Scriblerus feels happy in informing his readers, that the case represented in … January has been answered by several legal gentlemen, who have given as their opinions, that the regular publication of bans stamps a marriage with legality. Elizabeth P – is, consequently, to all intents and purposes, the wife of John P –, although the marriage took place while he was a minor. Of course, according to this decision, our fair correspondent, Mary F – r, cannot withdraw herself from those engagements from which she has such reason to desire a release.7

Runaway marriages

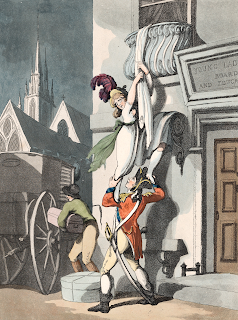

|

| Smuggling Out or Starting for Gretna Green by Rowlandson & Schutz Published by Ackermann (1789) DP872184 from Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. Ackermann, Rudolph, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics (January 1815)

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ackermann, Rudolph, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics (February 1815)

6. Ibid.

7. Ackermann, Rudolph, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics (April 1815)

Sources used include:

Ackermann, Rudolph, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics (Various)