From French Prison to English Pulpit

Alexander Stewart - sailor, prisoner and preacher

We recently came across the the inspiring story of a lad who, after ten years in a French military prison, become a well-respected preacher in London.

Alexander Stewart ran away to sea as a teenager. Born in Scotland in 1790, he left home in 1805. Without consulting his parents, he took a coach to England and joined the crew of a merchant ship.

Later in life he wrote an account of what happened. In it he records how, soon after becoming sailor, his ship was sailing off Brighton when:

‘The Mate exclaimed ‘a Lugger, a Lugger–she is coming up with us’. All eyes were immediately on her. The captain, he feared she was a French Privateer. In an instant the ship’s course was altered with a view to run her under the Brighton Battery; while some of us were ordered aloft to make more sail. But all was in vain.’

The lugger was indeed a privateer and it caught Stewart’s ship before they came under the safety of the guns at Brighton.

A few days later the crew, now prisoners, were landed at the port of Gravelines, in France.

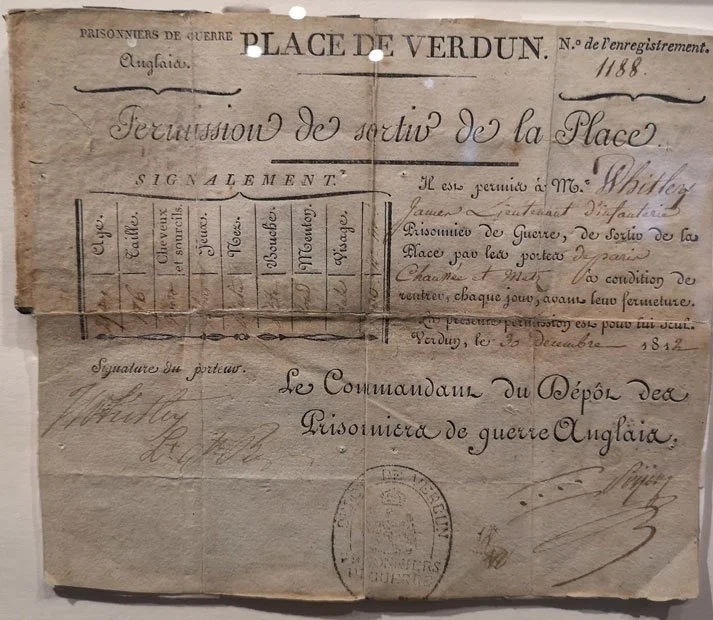

Here I first saw some of the French peculiarities—the notorious ceremony of taking our Depositions, viz, our names, ages, places of abode, occupations, station in the ship, etc., with our height, the colour of our hair, form of our face, with any peculiar marks by which we might be specially known.

A few days later the crew began their long march inland to prison.

We were tied to each other with a strong chord, much as you may see a number of horses at Smithfield, and escorted by a party of soldiers headed by two Drummers, beating what, I suppose, we should call the Rogue’s March, to give dignity to the scene.

Verdun, prison city in France. By James Forbes, also a prisoner in 1804.

A decade under lock and key

This first march took Stewart nearly 200 miles inland, to the fortress-turned-prison of Verdun in north-east France.

Prison life wasn’t too onerous at first.

We, as boys, with a number of old men who lived in the Barracks, were mustered every day, in front of the buildings, by the gensdarmes. With this exception we had the range of the town for the rest of the day.

He soon moved to another prison, where he described their food rations:

Here we had 1lb of brown bread per day, a little meat, nominally half a pound, but really not half that weight, for all the heads, legs, livers and other offal were counted as weight.

Stewart and three others eventually escaped but were recaptured after a few days.

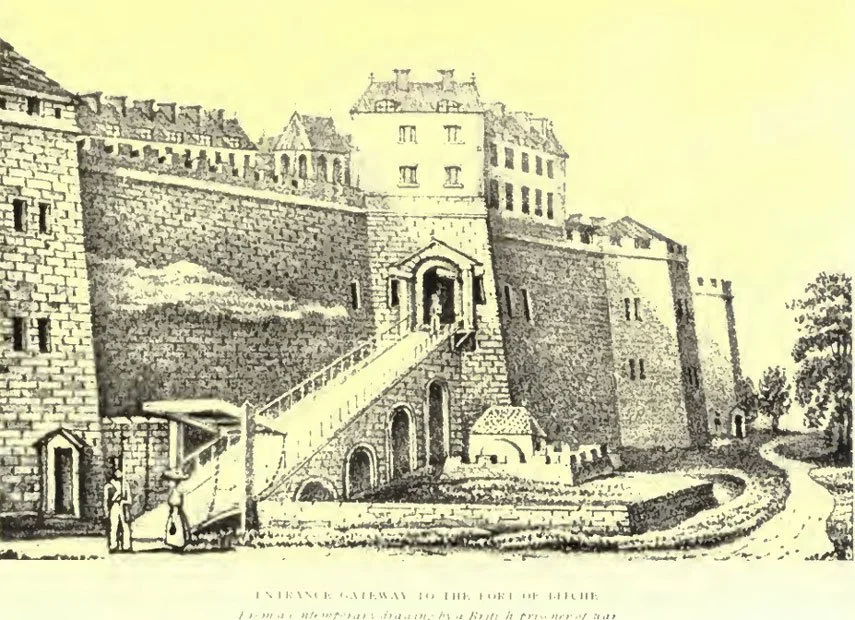

He was taken to Bitche (pronounced Beesh), a more secure prison.

In 1812 he moved on to a prison in Briançon, in the French Alps. A second escape attempt gave him just a few minutes of freedom before being captured once more.

A decade of learning and growth

In his account, Stewart recorded how he learned to speak French and improved his understanding of English grammar and pronunciation. He won respect as a teacher of inmates and as an interpreter.

Physically, Stewart matured into a robust figure who frequently took part in wrestling matches with other prisoners, and was often the winner. His physical prowess, along with his willingness to stand up to bullying from one prison governor, secured further respect from his peers.

Another prison governor was more appreciative of Stewart’s capabilities as an interpreter and writer, making him a trusted assistant in his office.

Parole card from Verdun, 1812. Officers were free to leave their rooms as long as they returned at night. National Army Museum.

Freedom and a revival of faith

Stewart acknowledges that in what he calls the ‘immoral’ atmosphere of prison, he initially gave little thought to God. He’d been raised to regularly attend church and had learned portions of scripture by heart.

By 1814 he was beginning to have conversations with devout believers. He was also on his way back to England, having parted company with his French overseers. As allied armies moved in on France, the authorities took less interest in English prisoners.

He went back to serving aboard ship, but as work dried up, became a teacher of French. He then trained to become a Congregational minister and in 1823 was appointed to lead a church in Barnet, north of London.

Stewart married and had fourteen children. He was a teacher and preacher for most of the rest of his long life. He died in 1874, aged 84.

According to his grandson, P Malcolm Stewart, his grandfather wrote the early portion his story when he was in his 40s. He wanted his children to know something of his ‘adventurous youth, when he ran away to sea, was captured by the French, and spent some ten years as a prisoner.’

Alexander Stewart’s account was published in 1946.

Entrance to the prison at Bitche

Andrew Knowles researches and writes about the late Georgian and Regency period. He’s also a freelance writer and editor for business. He lives with his wife Rachel, co-author of this blog, in the Dorset seaside town of Weymouth.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Source

The Life of Alexander Stewart - Prisoner of Napoleon and Preacher of the Gospel (1946).

Regency History

by Andrew & Rachel Knowles

We research and write about the late Georgian and Regency period.

Rachel also writes faith-based Regency romance with rich historical detail.