Introducing Gas Light to Regency London

Georgian gas lamps still operate in parts of central London. This one is on Birdcage Walk.

I hesitate to mention Jane Austen at the start of an article about gas lighting. We imagine her world illuminated by the sun, the moon and the flickering glow of fires and candlelight. The steady glow of gas lamps is more evocative of the Victorian streets walked by characters from the novels of Charles Dickens.

Yet gas lighting was not unfamiliar to some of Austen’s contemporaries. In the opening years of the nineteenth century it was experimental and by 1813 Westminster Bridge, in London, was lit by gas.

One of the earliest newspaper references to gas light is from October 1806. The Morning Herald, London, reports:

We hear that a British mine of wealth is on the eve of being worked…We allude to Mr Winson’s great plan of a general introduction of gas lights from the waste of smoke, which is a nuisance.

German inventor Frederick Winsor set up the National Light and Heat Company with a gas works in London and from late 1806 invited potential investors to view his ‘Experiments and Illuminations’ at 97 Pall Mall.

Early the next year he announced in the newspapers:

The Experiment “how to light a street,” will be made, by gracious permission of his Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, on Carlton Garden Wall, in St. James’s Park, on the 4th and 7th of April.'

However, on the day before the first demonstration, he announced that unfavourable weather meant it would be delayed. At the end of April the public demonstration still hadn’t taken place, although Winsor assured actual and potential investors that ‘The Lamps on Carlton Garden Wall have already been lighted twice’.

The wall was part of Carlton House, the palace of the Prince of Wales.

The first public demonstration of gas light

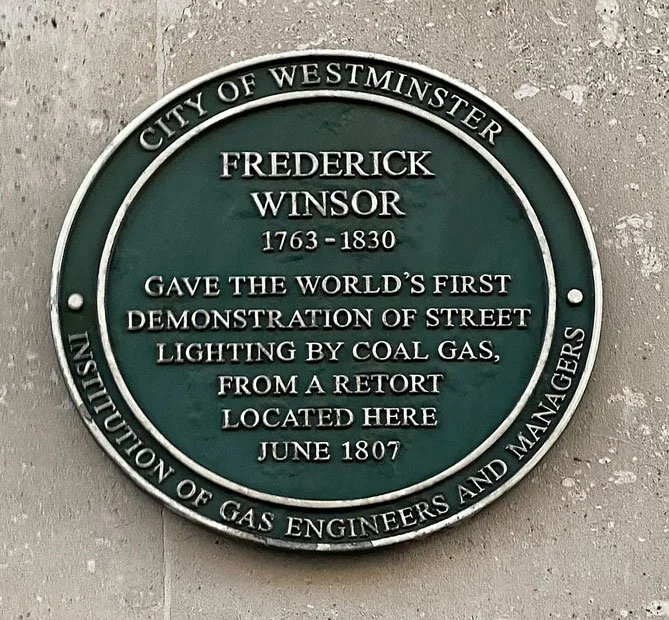

The delayed public display of the gas lamps finally took place on the king’s birthday, 4 June 1807. A plaque in Pall Mall commemorates the event.

The Morning Advertiser reported on it the following day.

The Proprietor of the Gas Lights fixed a variety of tubes along the wall of the Prince of Wales’s Gardens, in St James’s Park, which conveyed the gas to lamps placed at regular distances, and on the same being lighted, afforded the desired effect. The Park was thronged with spectators, anxious to witness this novelty.

On 8 June, Frederick Winsor placed his own announcement in the newspapers, celebrating the success of the display.

Thousands witnessed, on the 4th of June, the COMPLETE Success of my Experiments on a large Scale; for all the Lights, with and without glasses, dispersed within 2000 feet from my stove, burnt in equal brilliancy from Eight o’Clock in the Evening till Seven in the Morning.

Was gas good for your health? It seems that Winsor thought it might be. In the regular invitations for people to view his experiments, he now added a footnote:

Those afflicted with Coughs, &c. are welcome to inhale the Gas every Lecture-night - Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

Historic gas lamp outside St James’s Palace, London.

From novelty to everyday necessity

Winsor was keen to commercialise the process of lighting streets and buildings with gas. His attempts to achieve this, by setting up the Gas Light and Coke Company, were stalled for many months. The new company would allow him to raise the money needed to fund the project, but some people feared it was ‘a mere bubble to trick incautious people out of their money.’

An Act of Parliament had to be passed to allow the company to be set up. This was eventually passed on 9 June 1810, giving the the business the powers needed to make ‘Inflammable Air.’

In 1812, various newspapers reported on the illuminations to celebrate Wellington’s victory at Salamanca, and also the Prince Regent’s birthday (12 August). Reports included:

The space from White Chapel to Hyde Park exhibited one continuous train of light; the whole bright, but parts of it eminently splendid. Ackermann’s Repository was illuminated with Gas Lights, the effect of which was dazzling and novel.

Within a few years, gas lighting became much more commonplace. A few decades later, in the 1870s, it began to be replaced by electric lights.

I was prompted to look into Regency gas lights because of a campaign to save some of London’s oldest lamps. There are still about 1,300 functioning gas lamps in the city, with the oldest on Birdcage Walk. These carry the insignia of George IV.

There’s no record of Jane Austen seeing gas lighting on her visits to London, although it’s quite possible she did. However, the survival of the old lamps means we can still enjoy their glow when we visit the city.

Some of the oldest gas lamps in London, erected in the reign of George IV, are on Birdcage Walk.

Andrew Knowles researches and writes about the late Georgian and Regency period. He’s also a freelance writer and editor for business. He lives with his wife Rachel, co-author of this blog, in the Dorset seaside town of Weymouth.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Sources include:

The Public Ledger (1807)

The Morning Chronicle (1806)

Johnson’s Sunday Monitor (1807)

Regency History

by Andrew & Rachel Knowles

We research and write about the late Georgian and Regency period.

Rachel also writes faith-based Regency romance with rich historical detail.