Regency History Guide to the History of Ireland

Dublin in the early 1800s

The history of Ireland before 1780

Ireland has always been on the fringe of British history. The Romans didn’t pay it too much attention, and the first recorded invaders were Viking raiders in the 8th century. They came up against the kings of Ireland, over whom there was a High King.

In 1169 the Normans invaded and took over much of the island. Their influence waned over the centuries and by the 1400s, British control was limited to The Pale, an area around Dublin. It was protected by a ditch and rampart.

A parliament was set up in 1297, but its influence was limited to British-controlled Ireland.

It was Henry VIII who decided to take full control of Ireland and was proclaimed king of Ireland in 1542. However, it wasn’t until 1603, early in the reign of James I, that all of Ireland was brought under British control.

During the wars to capture Ireland the British confiscated land and gave it to settlers from England and Scotland. The settlers were Protestants, while the displaced Irish were Catholics.

In the 1600s the Irish rebelled and in the middle of the century Oliver Cromwell launched a brutal assault to stamp the Commonwealth’s authority across the island. More land was confiscated from the Irish and given to settlers from Britain.

War, famine and emigration, sometimes forced, had decimated the Irish population by the early 1700s. Those who remained were Catholic peasants and Protestant landowners, known as the Protestant ascendancy.

The Protestant ascendancy seeks more freedom from Britain

In the late 1770s the Protestants in Ireland began to form militia units, in order to guard against invasion. The British Army was being kept busy in the war against America, and there was a genuine concern of a French invasion. The militia were known as Irish Volunteers.

Throughout the 18th century, the Irish Protestants had developed their own culture. Their grand houses mirrored those being built on great estates in England, but their frustration at having limited control over their own government was not dissimilar to that of the American colonists.

Unlike the Americans, the Irish had their own parliament. In 1782, following a campaign by Irish Protestants led by Henry Grattan, this was given much more independence.

Maria Edgeworth, writing in 1819, describes what happened:

In 1781, the celebrated convention of delegates, from one hundred and forty-three corps of volunteers, assembled at Dungannon. Their resolutions were adopted also by the volunteers of the South; and at length Mr Grattan moved an address to the throne, asserting the legislative independence of Ireland. The address passed; the repeal of a certain act, empowering England to legislate for Ireland, followed; and the legislative independence of this country was acknowledged. This kingdom was then in a transport of joy, and the patriots and volunteers were at the height of their popularity.

Despite having won ‘legislative independence’, the Irish parliament was still effectively under the control of the government in London.

Many of the Protestant ascendancy seeking more independence for Ireland also wanted the often harsh restrictions on Catholics to be lifted.

Avondale House, Co. Wicklow, built 1777, a typical house of the Protestant ascendancy. Later the home of leading Irish nationalist Charles Stewart Parnell (photographed in 1984).

The United Irishmen aim for full independence

The American revolution had prompted a nervous British government to grant the Irish parliament a little more freedom. But the French revolution of 1789 sparked a further wave of agitation for complete independence.

In 1791 a group of Protestants met in Belfast to form the Society of United Irishmen. Their aim was, in partnership with Irish Catholics, for Ireland to become entirely self-governing.

Two years later, in 1793, Britain was at war with revolutionary France. For some, this was an opportunity for alliance. Theobald Wolfe Tone, a lawyer who helped found the United Irishmen, travelled to Paris, where he found the French enthusiastic to invade.

A French fleet with thousands of soldiers, and Wolfe Tone, arrived at Bantry Bay in December 1796. The army could have landed unopposed, except that the weather prevented it. The invasion didn’t happen.

Insurgency and secret societies

To add numbers to their cause, the United Irishmen sought the help of a Catholic secretive society known as the Defenders.

The Defenders emerged in rural Ireland during the 1780s, with the aim of protecting Catholics against the more aggressive tendencies of some Protestant groups. They were particularly active in the 1790s, attacking Protestant homes to steal weapons and committing acts of violence.

In some of her letters, written from Edgeworthstown in rural Ireland, Maria Edgeworth writes about the Defenders.

Edgeworthstown August 1794

There have been lately several flying reports of Defenders, but we never thought the danger near till to-day. Last night a party of forty attacked the house of one Hoxey, about half a mile from us, and took, as usual, the arms.

Edgeworthstown April 1795

The raising the militia has occasioned disturbances in this county. Lord Granard’s carriage was pelted at Athlone. The poor people here are robbed every night.

Edgeworthstown January 1796

My father is gone to a Longford committee, where he will I suppose hear many dreadful Defender stories: he came home yesterday fully persuaded that a poor man in this neighbourhood, a Mr Houlton, had been murdered, but he found he was only kilt [Irish slang for injured], and “as well as could be expected” after being twice robbed and twice cut with a bayonet.

Maria’s letters give us an insight into how uncomfortable it was to be a Protestant landlord in rural Ireland in the 1790s, surrounded by thousands of peasant farmers who nursed grievances that went back generations.

The attempts by the Protestant United Irishmen to ally with the Catholic Defenders highlights the complexity of Irish history. While they were separated by religion, they had a common enemy in the British establishment.

However, the Defenders did not prove to be reliable as allies because they lacked central leadership. They were just one of several secret societies in Ireland at that time.

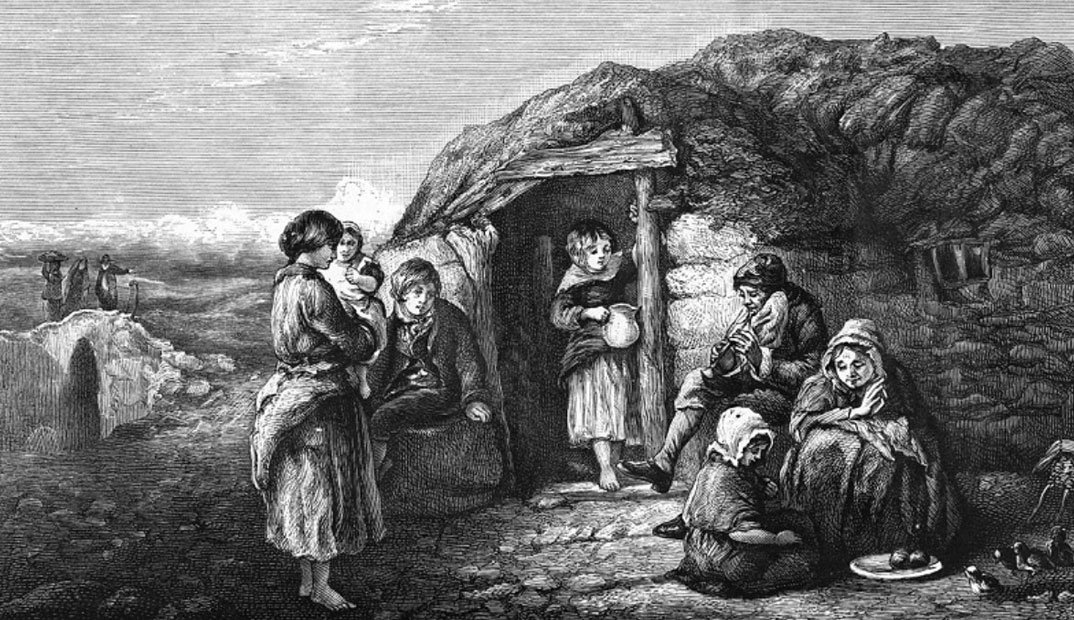

Irish peasant cabin in the early 1800s

The Rebellion of 1798

Some of the founders of the United Irishmen did not want their movement to lead to an armed rebellion. This didn’t stop those who did, and in early 1798 they were ready to take action.

The authorities knew that trouble was coming and in a bid to extract information about local ringleaders, the authorities treated people harshly.

The date chosen by the United Irishmen was 23 May. Their army of volunteers would seize Dublin, which would signal their followers across the country to rise up.

The Dublin rising failed because the authorities were forewarned and occupied the sites where the rebels were to gather. A rising in south-east Ireland, around Wexford, enjoyed initial success but the rebels were then defeated in a battle at New Ross.

Unable to march towards Dublin the rebels camped at Vinegar Hill near Enniscorthy. About 16,000 people enjoyed several days of mild June weather, waiting for someone to lead them to victory.

Unfortunately, on 21 June they were attacked and routed by a military force.

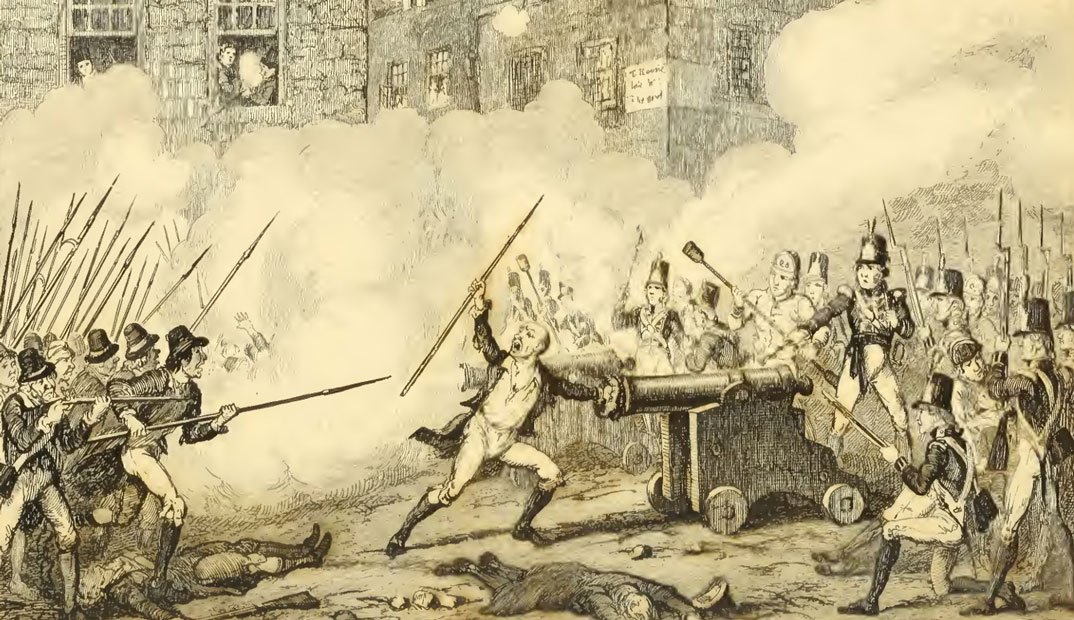

The rebellion of 1798, George Cruikshank

While local risings had been put down, this didn’t stop the French from having another go. In August 1798 they landed about 1,000 men on the coast of County Mayo. Thousands of Irish flocked to join the army, but they lacked equipment and training. Despite this, the French defeated a British force in the brief Battle of Castlebar.

This success was short-lived. Within a couple of weeks the French surrendered to a larger British army, after defeat at Ballinamuck.

A month later, in October 1798, yet another French army tried to land in Ireland. It was accompanied by Wolfe Tone. The Royal Navy engaged the French, and Tone’s ship was captured. He was recognised, tried and sentenced to death. On 19 November 1798 he took his own life, shortly before his date with the executioner.

Maria Edgeworth records something of what it was like to live through these events:

Towards the autumn of the year 1798, this country became in such a state, that the necessity for resorting to the sword seemed imminent. Even in the county of Longford, which had so long remained quiet, alarming symptoms appeared, not immediately in our neighbourhood, but within six or seven miles of us, near Granard. The people were leagued in secret rebellion, and waited only for the expected arrival of the French army, to break out.

Union of Ireland and Great Britain in 1800

On 31 December 1800 the Parliament of Ireland was merged with that of the United Kingdom.

This ensured that Irish Members of Parliament now had a voice in Westminster. It was an attempt to improve relations between Britain and Ireland, with security and economic benefits for all.

Part of the deal that led to the Union was that remaining discrimination against Roman Catholics would cease. However, George III vetoed this. It wasn’t until 1829, under Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, that the final restrictions on Catholics were lifted.

Wellesley was himself part of the Protestant ascendancy in Ireland. Born in Dublin, the family home was Dangan Castle in County Meath.

Not all the Protestant ascendancy was in favour. Richard Edgeworth, Maria’s father, was a relatively new Member of Parliament and he voted against it. She writes:

After stating many arguments in favour of what appeared to him to be the advantages of the union; he gave his vote against it, because he said he had been convinced by what he had heard in that house that night, that the union was at this time decidedly against the wishes of the great majority of men of sense and property in the nation.

A final flourish for the United Irishmen

In July 1803 Robert Emmet, of the United Irishmen, led another rebellion against the Irish authorities.

It was a short-lived affair which suffered from the problems of previous attempts—the authorities knew in advance and people did not turn up in the numbers he had hoped for.

He attempted to storm Dublin Castle with about 80 men. The attack quickly fizzled out and he went into hiding. Soon captured, his final words before execution include the phrase:

Let no man write my epitaph…When my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then and not till then let my epitaph be written.

Andrew Knowles researches and writes about the late Georgian and Regency period. He’s also a freelance writer and editor for business. He lives with his wife Rachel, co-author of this blog, in the Dorset seaside town of Weymouth.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Sources include:

Ireland A History, Robert Kee

The Life and Letters of Maria Edgeworth

Memoir of Richard Lovell Edgeworth

Regency History

by Andrew & Rachel Knowles

We research and write about the late Georgian and Regency period.

Rachel also writes faith-based Regency romance with rich historical detail.