Maria Edgeworth’s Ireland

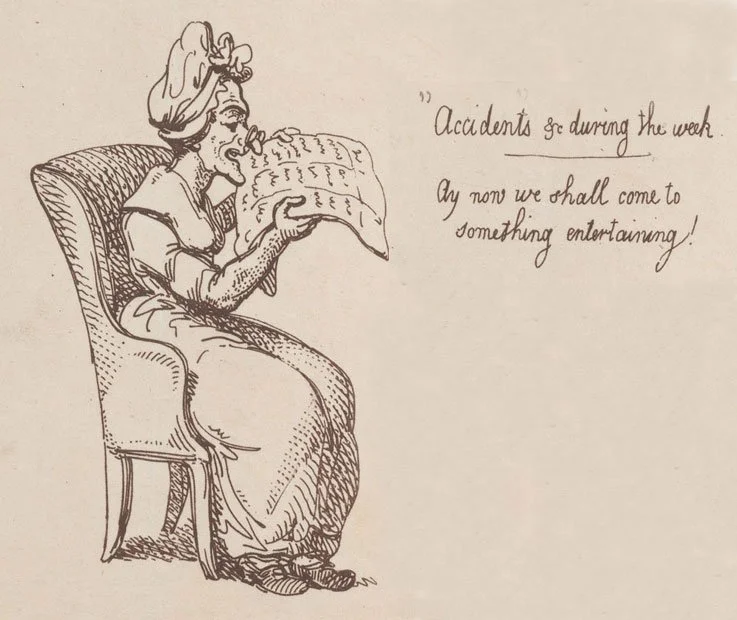

Maria Edgeworth - from an 1808 edition of her work.

Maria Edgeworth was the most financially successful author in early 1800s Britain.

Like Jane Austen, Maria (pronounced, we’re told, as Mar-eye-a), spent much of her life in a quiet rural home.

Unlike Austen, that home was in Ireland, and her early books were written during a time of dramatic unrest and a French invasion.

What was going on in Ireland during Maria Edgeworth’s life?

From the age of about 14, Maria lived much of her life in Edgeworthstown, County Longford. It’s in central Ireland, about 60 miles from Dublin.

The name is a clue that the Edgeworths had been in the area for a long time. They were part of the Protestant Ascendancy–that is, they were an English family that had taken over estates in Ireland, mostly in the 1500s.

Maria was born in England in 1768. A few years later, her father, Richard Edgeworth, took the family to their estate in Ireland.

She sometimes left Ireland, travelling in England and into mainland Europe. But Edgeworthstown remained her home and she died there in 1849.

Why the interest in Maria? She was one of the most well-known authors of her time and Jane Austen was a fan.

Edgeworth House, Edgeworthstown, in 1825

The Ireland that Edgeworth experienced

Maria and her family enjoyed an active social life with other Protestant aristocrats and gentry. This included the family of Kitty Pakenham, who married the Duke of Wellington. Kitty was a friend of Maria.

Anti-Catholic laws had given land and power to Protestants. The land was worked by the Catholic Irish, as tenants. Richard, Maria’s father, was no exception to this.

Maria described the Irish as excelling in ‘wit and humour’, with a ‘generous temper’. They were, however, often abused by landlords, and by the middlemen who collected rents. Many were desperately poor and lived in one-roomed hovels.

The Irish formed secret societies to protect themselves from abuse. The Irish Defenders were one such group. In a letter to her aunt in 1796, she wrote:

My father is gone to a Longford committee, where he will I suppose hear many dreadful Defender stories: he came home yesterday fully persuaded that a poor man in this neighbourhood, a Mr Houlton, had been murdered, but he found he was only kilt, and “as well as could be expected,” after being twice robbed and twice cut with a bayonet.

Irish tenant farming family pictured in the late 1700s.

Rumours of rebellion

Some of the Protestant Ascendancy were keen for Ireland to gain more independence from Great Britain. Enthusiasm for this was stoked by the Americans breaking free of British rule, and then by the spirit of revolution in France.

This led, in 1791, to the Society of United Irishmen. Founded by Protestants, it sought to work with Catholics to achieve a higher degree of Irish government. The United Irishmen allied themselves with the Defenders.

The rebels also enjoyed the support of the French, who attempted to land an army in December 1796. Weather prevented the invasion, but it didn’t deter those wanting to achieve change through violence.

In May 1798 Maria wrote:

When we set off from the church door for Edgeworthstown, the rebellion had broken out in many parts of Ireland.

Soon after we had passed the second stage from Dublin, one of the carriage wheels broke down. Mr Edgeworth went back to the inn…to get assistance. Very few people were to be found, and a woman who was alone in the kitchen came up to him and whispered, “The boys (the rebels) are hid in the potato furrows beyond.”

She goes on to say that they continued without being stopped ‘by any of the boys’. But they then passed a cart that had been turned into a gallows for a victim of the rebels.

Rebels destroying an house by George Cruikshank., drawn decades after the events of the 1790s.

French boots on Irish ground

In August 1798, the French successfully landed a small army on the west coast of Ireland. They fought, and defeated, a British force at Castlebar.

Maria wrote:

We have this moment learned from the sheriff of this county, Mr Wilder, who has been at Athlone, that the French have got to Castlebar. They changed clothes with some peasants, and so deceived our troops.

Her father, in command of a corps of yeomanry, wanted to help, but their weapons had not arrived from Dublin. There was considerable confusion.

We who are so near the scene of action cannot by any means discover what number of the French actually landed: some say 800, some 1,800, some 18,000, some 4,000. The troops march and countermarch, as they say themselves, without knowing where they are going, or for what.

Two weeks later, the French surrendered. On 1 January 1801, The Act of Union merged the Irish and British parliaments.

More trials and tribulations for Ireland

The 1820s saw active campaigning for the removal of the restrictions on Catholics, led by Daniel O’Connell. Maria lived to see this, and to witness the Irish Potato Famine of 1845 onwards. The condition of the Irish poor, which had deteriorated over Maria’s lifetime, led to around a million of them dying.

Even before the famine, Maria felt Ireland’s pain. She wrote, in 1834:

It is impossible to draw Ireland as she now is in a book of fiction–realities are too strong, party passions too violent to bear to see… We are in too perilous a case to laugh, humour would be out of season, worse than bad taste.

Sir Walter Scott once said to me, “Do explain to the public why Pat, who gets forward so well in other countries, is so miserable in his own.” A very difficult question: I fear above my power. But I shall think of it continually, and listen, and look.’

The Edgeworth family in 1787, when Maria was about 20 years old. By this time her father, Richard, was on wife number three. He had four in total, and 22 children.

Andrew Knowles researches and writes about the late Georgian and Regency period. He’s also a freelance writer and editor for business. He lives with his wife Rachel, co-author of this blog, in the Dorset seaside town of Weymouth.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Sources include:

The Life and Letters of Maria Edgeworth

Maria Edgeworth A Literary Biography by Marilyn Butler (1972)

Regency History

by Andrew & Rachel Knowles

We research and write about the late Georgian and Regency period.

Rachel also writes faith-based Regency romance with rich historical detail.