|

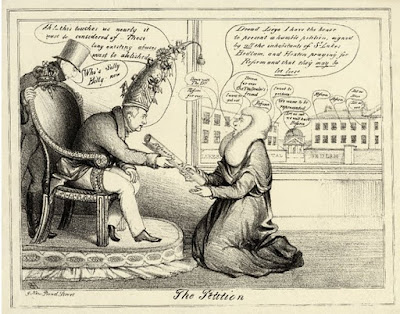

Princess Charlotte

from La Belle Assemblée (1807) |

Princess Charlotte goes to the seaside

Princess Charlotte first visited Weymouth in 1799 whilst her grandparents, George III and Queen Charlotte, were staying there. The king had visited the town during the summer of 1789 whilst recuperating from his first serious bout of mental instability and liked Weymouth so much that he returned there almost every year until 1805.

Princess Charlotte arrived in Weymouth on 28 August, accompanied by her governess, the Countess Dowager of Elgin. She stayed in the house taken for her on Charlotte Row. A few days later, on 1 September, she bathed in the sea for the first time. As a lively three-year-old, Charlotte loved to collect shells on the beach. During her stay, she visited the village of Upwey and her aunts bought her toys from Mr Ryall’s toyshop.

At midnight on 16 September, Princess Charlotte’s father,

George, Prince of Wales, arrived in Weymouth to visit his daughter. Unlike his father, the Prince of Wales did not like Weymouth. This is not surprising given that the King and his eldest son disagreed on virtually everything. The Prince of Wales preferred the freedom he found away from the royal court at the more fashionable resort of Brighton. However, on this occasion, he managed to overcome his dislike of the town sufficiently to visit his daughter.

The King’s party left Weymouth on 14 October, followed by Princess Charlotte and Lady Elgin on 23 October.

|

| Weymouth beach (2012) |

Recuperating in Weymouth 1814

In 1814, Charlotte visited Weymouth again, to try a sea water cure for the severe pains she was suffering in her knee. She was also emotionally worn down at this time, as her father’s reaction to her behaviour after breaking off her engagement to Prince William of Orange had been severe. Her party included Countess Rosslyn, Countess Ilchester, Mrs Campbell, the Misses Coates, General Garth and the Reverend Dr Short.

A royal welcome

|

| Gloucester Lodge, Weymouth (2012) |

Princess Charlotte arrived at Gloucester Lodge on 10 September 1814, where she was warmly welcomed by the inhabitants of Weymouth who had gathered on the Esplanade to applaud her arrival. Two days later, Henry Hayes Tozard, the Mayor of Weymouth, organised a formal celebration of her visit, with a display of standards at the custom house, Harvey’s Library and the Esplanade and on ships in the harbour, and a general illumination in the evening.

On 14 September, the mayor, aldermen and principal burgesses waited on Princess Charlotte and formally addressed her with a welcoming and dutiful speech:

We regard the auspicious appearance of your Royal Highness amongst us, not only as a happy omen of the future prosperity of the town, but as a revival of the joyful sensations we formerly experienced on the visits of your august grandfather, the paternal sovereign of a grateful people.1

Sea bathing

Charlotte went sea bathing every other day in an effort to cure the pains in her knee. According to a letter from her friend,

Margaret Mercer Elphinstone, to Lord Grey, Charlotte’s health was becoming worse and the pains in her knee were preventing her from sleeping. Mr Keate came down from London to attend her.

Miss Elphinstone’s letter also claimed that 'the Prince has positively refused to allow her to drive her ponies there, as he says it would collect a mob at the door every time she went out.' However, Huish’s biography suggests that she did go for morning rides and was able to enjoy the beautiful countryside, and in particular, her favourite drive to the charming village of Upwey.

During her stay, Princess Charlotte attended services at the Melcombe church, which she found was far too small for the number of the people wishing to attend and was therefore rather hot and overcrowded.

Isle of Portland

|

| Portland Bill (2012) |

During her stay in Weymouth, Princess Charlotte was able to satisfy her desire to visit the Isle of Portland. Although the short voyage was tedious because of lack of wind, she was fascinated by the huge expanse of barren rock. Huish recorded:

She was going too near the verge of the rocks, which presented a high perpendicular face to the ocean, when one of her ladies, alarmed at her boldness, implored her to go no further; she replied, in the most significant manner: ‘I wish every one standing on the brink of destruction could retrace their steps as easily as I can.’2

Princess Charlotte eagerly sought the details of the East India company ships, the

Halswell and the

Abergavenny, which had been wrecked off the island.

Abbotsbury, Lulworth and Corfe

Charlotte was cordially received by the Countess of Ilchester at Abbotsbury Castle. Abbotsbury village was once home to a monastery of Benedictine monks and the princess was pleased to visit the famous decoy there.

|

| The decoy, Abbotsbury Swannery (2012) |

|

|

She also visited

Lulworth Castle, the seat of Thomas Weld, and

Corfe Castle, the property of Henry Bankes, where she marvelled at the ancient castle ruins.

|

| Corfe Castle (2012) |

An anniversary celebration

According to Huish, 'On the anniversary of the jubilee, the day was observed by her Royal Highness with every testimony of regard.'3 I believe that the anniversary referred to is that of George III’s accession to the throne, which was on 25 October. Princess Charlotte gave out gifts of money and bibles to the poor, and the nobility were invited to the King’s Lodge where they were entertained by the famous Italian minstrel, Signor Rivolta, who performed a concert on eight instruments at one time. There was also a magnificent firework display with an emblematical device of the king.

Charlotte had one final marine excursion, on board his Majesty’s ship, Zephyr, before leaving Weymouth on 15 November, breaking her journey at Salisbury where she was able to admire the cathedral before returning to Cranbourne Lodge.

Another seaside holiday 1815

Princess Charlotte visited Weymouth again the following year when the pains in her knee began to reoccur. Arriving in Weymouth at the end of July, the princess was, once again, enthusiastically received, and a general illumination was given in her honour. She stayed until the end of the year, leaving Weymouth on 1 January 1816.

|

| Weymouth beach (2012) |

On board the Leviathan

On one occasion during this visit, Charlotte was on board the royal yacht when the Leviathan fired a salute and Captain Nixon came on board to pay his respects. At her request, the princess was rowed across to the man-of-war, despite the disapproval of the Bishop of Salisbury, who was of the party. She insisted on ascending the side of the boat rather than have a chair of state let down for her and then proceeded to inspect the whole ship before descending over the side of the boat in the same manner. Though her behaviour was applauded by many, it was chastised by others as unladylike.

Weymouth remembers

The marriage of Princess Charlotte to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg was celebrated with enthusiasm in Weymouth in 1816; her death the following year was most solemnly mourned.

A letter of commiseration dated 20 November 1817 said:

Yesterday being the day appointed for the funeral of the ever-to-be-regretted Princess Charlotte of Wales, it was observed here with the most mournful solemnities.4

We had witnessed, during two successive seasons, which she passed among us, those charitable dispositions, those affable and endearing manners, those elegant attainments, which formed her bright character.5

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) From Huish, Robert, Memoirs of her late royal highness Charlotte Augusta, Princess of Wales (Thomas Kelly, 1818, London)(p151)

(2) From Huish, Robert, Memoirs of her late royal highness Charlotte Augusta, Princess of Wales (Thomas Kelly, 1818, London)(p158)

(3) From Huish, Robert, Memoirs of her late royal highness Charlotte Augusta, Princess of Wales (Thomas Kelly, 1818, London)(p165)

(4) From Huish, Robert, Memoirs of her late royal highness Charlotte Augusta, Princess of Wales (Thomas Kelly, 1818, London)(p638)

(5) From Huish, Robert, Memoirs of her late royal highness Charlotte Augusta, Princess of Wales (Thomas Kelly, 1818, London)(p639)

Sources used include:

Chedzoy, Alan, Seaside Sovereign - King George III at Weymouth, (2003)

Hibbert, Christopher, George IV (1972, 1973)

Huish, Robert, Memoirs of her late royal highness Charlotte Augusta (1818)

Parissien, Steven, George IV, The Grand Entertainment (2001)

Times Digital Archive

All photographs © RegencyHistory.net