|

| HRH Ernest, Duke of Cumberland from A Biographical Memoir of Frederick, Duke of York and Albany by John Watkins (1827) |

The scandalous story caused a lot of gossip. In A Reason for Romance, the heroine Georgiana reads the account of the attack in The Times, excerpts from which are included below, and is desperate to talk about it. Popular opinion at the time was so against the Duke that it was generally believed that he had murdered his valet. But was Sellis responsible for the attack on the Duke? And did he commit suicide or was he murdered?

In the early hours of 31 May 1810, Ernest, Duke of Cumberland, asleep in bed, was woken by being hit over the head. Initially he thought a bat had got into his bedroom.

The Times, 1 June 1810, reported:

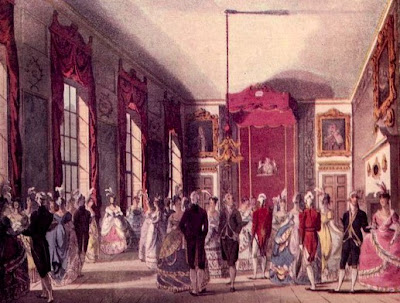

On Wednesday, the Duke of Cumberland dined at Greenwich. His Royal Highness returned to town, about eight o’clock, in an open carriage and four. The Duke then went to the Concert for the benefit of the Royal Society of Musicians. His Royal Highness returned to his apartments in St James’s Palace about half-past twelve o’clock, and went to bed about one. About two o’clock, he was awoke by the assassin, when he was sound asleep.1

Who, being upon his oath, saith, that, before three o’clock this morning, being in bed and asleep, he received two blows upon his head, which awoke him, and, upon starting up, he received two other blows upon his head, which, being accompanied with a hissing noise, it occurred to him that some bat had flown against him, being between sleeping and waking, and immediately received two other blows; there was a lamp burning in the room, but he did not see any body; that there was a night table standing near the bed side, where a letter lay which was covered with blood.

His Royal Highness says, he then got up and made for the door, which opens at the head of the bed; he then received a wound upon his right thigh with a sabre; he then called out to Neale, his page, and, upon returning to the bedroom with Neale, he perceived that the door leading to the yellow room, was wide open, which is always locked the last thing when he gets into bed; a naked sword had been dropped, which he supposes must have given the wound in this thigh.2

The Times report continued:

On his Royal Highness extricating himself from the attack of the villain, and getting out of his bedroom, he exclaimed aloud to his valet in waiting, repeatedly, ‘Neale, Neale, I am murdered! I am murdered!’ Neale, who was sleeping in an adjoining room, got up instantly; and the Duke informed him of the particulars, and said, the murderers were in his bedroom. Neale armed himself with a poker, and he and his Royal Highness proceeded along the passage; when Neale stepped upon the sword with which the Duke had been attacked, which was one of the Duke’s, and had been sharpened within these few days.3

Joseph Sellis had taken out his Royal Highness’s uniform and the sword, and brought them into his bedroom for a regiment inspection which did not take place, and Sellis afterwards returned the regimentals to the wardrobe, but left the sword in the bedroom, where informant believes he saw the sword some time yesterday.4

|

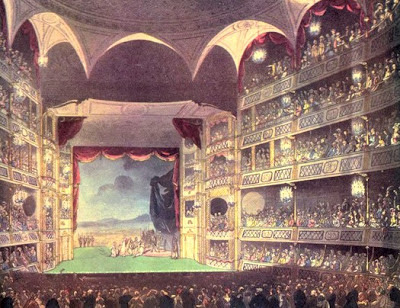

| St James's Palace from The Beauties of England and Wales Vol X by EW Brayley, J Nightingale and J Brewer (1814) |

When the servants went to arouse Joseph Sellis, they found that the door to his apartment was locked. They hurried round to his room by the other available route through the state apartments, the doors to which were, surprisingly, unlocked. By the time they entered the room, Sellis was dead; his throat had been cut with a razor.

The Times reported:

Upon the alarm being given in the Palace, Lieut Buller, with a Serjeant and several men, who were on duty in the Palace, entered his Royal Highness’s apartments, and found the villain on his bed with his head nearly severed from his body; the blood that issued from him had nearly covered the bed-clothes and furniture.5But why would Sellis attack the Duke?

The Times stated:

No reason has been assigned sufficient to account in the smallest degree for this accumulation of crime and ingratitude.6

His Royal Highness further saith, that the said Joseph Sellis had not incurred his displeasure, and that he had not any reason to think ill of him.7

Another possible motive is that the vehemently anti-Catholic Duke, who had a malicious streak, was inclined to poke jibes at Sellis who was a Sardinian and supposedly Roman Catholic and that Sellis could not take any more of it. However, Sellis had his children baptised according to the rites of the Church of England, so this argument loses much of its force.

Another theory is that he was seized by a fit of insanity.

Probably the best suggestion of a motive is jealousy and theft. Sellis was jealous of the other valet Neale who appeared to be given preferential treatment over him. His plan may have been to attack the Duke and rob him and leave Neale to take the blame. As Neale was the valet on duty that night, suspicion would most naturally have fallen on him.

Once a thief…

Sellis had once been valet to a Mr Church in America and had been accused of thievery before New York magistrates but there was insufficient evidence to convict him. Sellis left America for England and after first working for Lord Mount Edgecumbe, he moved into service for the Duke.

What went wrong?

Sellis used the Duke’s sword as his weapon, but he miscalculated his attack and hit the Duke with the flat of the blade rather than the edge, which only succeeded in rousing the Duke rather than killing him.

When help was called, Sellis escaped to his room, but he was unable to eradicate the evidence of his crime before the servants came knocking on his door. Rather than face the consequences of his actions, he committed suicide.

The jury’s verdict: Sellis committed suicide

The murderous Duke?

Did the Duke murder his valet? Probably not. I do not think that the Duke can have killed Sellis because of his own injuries and it seems unlikely that the dozen or so witnesses could have corroborated each other’s testimonies if they were not speaking the truth.

Also, Sellis’s door was locked. It is impossible to believe that the Duke, who had been viciously injured in the attack, could have killed Sellis and then set it up to look like suicide.

Another interpretation?

But what if there is another interpretation of what happened? What if the attack was set up by someone who wanted to get rid of Sellis? The obvious culprit would be Sellis’s rival valet, Neale.

The reason that I still feel uncertain as to whether this was truly what happened is that the attempted murder was such a botched affair. How difficult is it to kill someone with a sword? And why use the sword anyway when Sellis proved how effective a razor was at killing someone when he committed suicide, if, indeed, he killed himself.

Or what if Sellis used the sword against the Duke in anger or self-defence, in the heat of the moment, during an argument over his wife or money or his recent dispute with Neale, and then committed suicide when he realised what he had done?

A libel action

In 1832, the matter raised its ugly head again when the Duke brought a libel action against Josiah Phillips, author of a book called The Authentic Records of the Court of England for the last Seventy Years in which the writer accused the Duke of murdering Sellis to prevent him from exposing the Duke’s alleged homosexual acts with his other valet, Neale.

At the trial, it was proved that the book’s information was not sound, and Phillips was found guilty of libel.

Updated 15 May 2020

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

6. Ibid

7. Stockdale op cit.

The Times digital archive