|

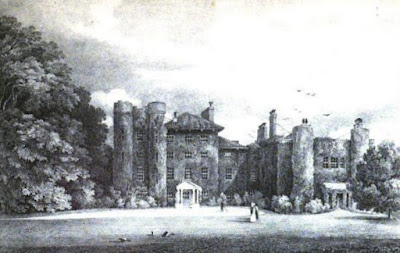

| The Oaks from Select Illustrations of the County of Surrey by GF Prosser (1828) |

When I was a girl, I lived on Woodmansterne Road in Carshalton, Surrey (though my husband argues that it is really in London as it is part of the London Borough of Sutton). I often visited nearby Oaks Park with my brothers.

Deep in the depths of the park lie the ruins of The Oaks – the villa of Edward Smith-Stanley, 12th Earl of Derby. The Earl had a passion for horse racing, and it was here that two of the British Classic horse races were conceived: the Epsom Oaks and the Epsom Derby.

Lambert’s Oaks

According to Prosser's Select Illustrations of the County of Surrey (1828), The Oaks

… is pleasantly situated on Banstead Downs, in the parish of Woodmanston; the healthiness and convenience of the situation for the enjoyment of field sports, attracted the notice of a society of gentlemen called the Hunter’s Club, to whom the land was leased by Mr Lambert, whence it was long known as ‘Lambert's Oaks’. They built a small house, designed for the festive meetings and general convenience of the society to partake of the diversions of the chase.1

General Burgoyne

| |

| The Oaks by John Collet c1762 © British Museum 1875,0814.961 under a Creative Commons licence CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 |

Hughson’s London (1808) described The Oaks:

General Burgoyne purchased the lease, and built a dining room forty-two feet by twenty-one, with an arched roof, elegantly finished; twenty-eight small cased pillars of fine workmanship, and a concave mirror at each end. The dining table is of plain deal boards, in conformity to the style of a hunting seat. The red hall entrance is small, but elegant: it contains two landscapes, and a few other pictures. The drawing room, on the first floor, is an octagon, ornamented with a variety of small pictures. It commands a prospect of Norwood, Shooter's Hill, many churches in London and its environs, Hampstead, Highgate, &c.2

Prosser also described The Oaks:

On the ground floor is a good dining-room, built by general Burgoyne, forty-two feet in length by twenty-one in breadth, including an arched recess at each end; and eighteen feet in height. It is ornamented with twenty-six small cased Corinthian columns, bearing a cornice; various medallions also adorn the walls. Adjoining the west end is a drawing-room thirty-three feet by thirty-eight. The other apartments though not spacious are numerous, and replete with convenience; those on the north front command a distant view of London and its neighbouring eminences. The exterior of the building, from its ancient style of architecture, and being entirely clothed with ivy, presents a pleasing and venerable appearance.3

General Burgoyne extended and improved the estate before selling it to his nephew, Edward Smith-Stanley, 12th Earl of Derby. He

… planted the grounds, and created here a pleasant summer retreat, admirably adapted for the pursuit of his favorite amusements, hunting and shooting. He also purchased some adjoining land; and the whole tenement, in its improved state, he sold to the present earl of Derby.4

The Earl made his own improvements to the house:

The earl … added, at the west end, a large brick building, with four towers at each corner; and there is a similar erection at the east end, which renders the structure uniform, and gives an elegant Gothic appearance.5

Despite being only a hunting box, the house must have been of a considerable size as, according to Hughson:

His lordship can accommodate his guests with upwards of fifty bed chambers.6

The Earl also extended the grounds:

The pleasure grounds his lordship has much enlarged, by enclosing a part of the common, which has since been planted, and the whole, nearly three miles in circumference, has been arranged with much good taste. A short distance south-east of the house is a remarkable old beech tree, the boughs of which are curiously interwoven and grown into each other.7

The Fête Champêtre of 1774

To celebrate his imminent marriage to Lady Elizabeth ‘Betty’ Hamilton, sister to Douglas Hamilton, 8th Duke of Hamilton, the Earl of Derby held a Fête Champêtre at The Oaks on 9 June 1774. For this elaborate alfresco entertainment, a magnificent temporary pavilion, designed by Robert Adam, was built in the grounds.

Mrs Delany described the Fête Champêtre in a letter to Mrs Port of Ilam:

I think it a fairy scene that may equal any in Madame Danois; nothing at least in modern days has been exhibited so perfectly magnificent – everybody in good humour, and agreed that it exceeded their expectation. The master of the entertainment (Lord Stanley), was dressed like Reubens, and Lady Betty Hamilton (for whom the feast was made), like Reubens’ wife. The company arriving, and partys of people of all ranks that came to admire, made the scene quite enchanting, which was greatly enlivened with a most beautiful setting sun breaking from a black cloud in its greatest glory.

After half an hour’s sauntering the company were called to the other side, to a more confined spot, where benches were placed in a semicircle, and a fortunate clump of trees in the centre of the small lawn hid a band of musick; a stage was (supposed to be formed) by a part being divided from the other part of the garden, with sticks entwined with natural flowers in wreaths and festoons joining each. A little dialogue between a Sheperd and Sheperdess, with a welcome to the company, was sung and said, and dancing by 16 men and 16 women figuranti’s from the Opera lasted about half an hour; after which this party was employed in swinging, jumping, shooting with bows and arrows, and various country sports.

The gentlemen and ladies danced on the green till it was dark, and then preceded the musick to the other side of the garden, the company following, where a magnificent saloon had been built, illuminated and decorated with the utmost elegance and proportion: here they danced till supper, when curtains were drawn up, which shewed the supper in a most convenient and elegant apartment, which was built quite round the saloon of a sufficient breadth and height to correspond with the saloon; after the supper, (which was exceeding good, and everybody glad of it as the evening had begun so very early, all the company being assembled in the saloon,) an interlude, in which a Druid entered as an inhabitant of the Oaks, welcomed Lady Betty Hamilton, and described the happiness of Lord Stanley in having been so fortunate, and in a prophetic strain foretold the happiness that must follow so happy an union, which, with chorus’s and singing and dancing by the Dryads, Cupid and Hymen attending and dancing also, it concluded with the happiness of the Oak making so considerable a part in the arms of Hamilton; a piece of transparent painting was brought in, with the crest of Hamilton and Stanley, surrounded with all the emblems of Cupid and Hymen, who crowned it with wreaths of flowers. From the great room in the house a large portico was built, which was supported by transparent columns and a transparent architecture on which was written, ‘To Propitious Venus.’ The pediment illuminated, and obelisks between the house and saloon. People in general very elegantly dressed: the very young as peasants; the next as Polonise; the matrons dominos; the men principally dominos and many gardiners, as in the Opera dances.8

|

| Plan of pavilion for Fête Champêtre at The Oaks from The Works in Architecture of Robert and James Adam by R&A Adam (1773) |

The interest of the piece was greatly increased by the excellent performance of Mrs Abingdon; it was afterwards represented in 1782 at Drury Lane Theatre with much success.9

The birth of two horse races

Sadly, all that is left of The Oaks today is the stable block and a few signboards, but the name of the house and its owner are commemorated in a sport that the Earl of Derby was passionate about – horse racing.

A plaque on one of the walls of the stables that still stand reads:

|

| Stables at The Oaks © A Knowles (2016) |

In 1779, whilst at dinner with the Duke of Richmond and Sir Charles Bunbury, Lord Stanley, 12th Earl of Derby, named a new horse race – The Oaks – after the house that once stood here. In 1780 another race – The Derby – was conceived. The Oaks was demolished in 1950 after war damage.10

|

| Plaque on wall of stables, The Oaks © A Knowles (2016) |

Notes

1. Prosser, George Frederick, Select Illustrations of the County of Surrey (1828).

2. Hughson, David, London; being an accurate history and description of the British Metropolis and its neighbourhood Volume V (1808).

3. Prosser op cit.

4. Ibid.

5. Hughson op cit.

6. Ibid.

7. Prosser op cit.

8. Delany, Mrs, The autobiography and correspondence of Mary Granville, Mrs Delany (1861).

9. Prosser op cit.

10. Plaque on wall of The Oaks, photographed 2016.

Sources used include:

Adam, Robert and Adam, The Works in Architecture of Robert and James Adam (1773)

Burgoyne, John, The Maid of the Oaks: A new dramatic entertainment. As it is performed at the Theatre-Royal, in Drury-Lane (1775)

Burgoyne, John, The Maid of the Oaks: A new dramatic entertainment. As it is performed at the Theatre-Royal, in Drury-Lane (1775)

Crosby, Alan G, Stanley, Edward Smith, 12th Earl of Derby (1752-1834), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Sept 2004, accessed 29 May 2018)

Debrett, John, The Peerage of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1820)

Delany, Mrs, The autobiography and correspondence of Mary Granville, Mrs Delany (1861)

Draper, P, The House of Stanley (1864)

Hughson, David, London; being an accurate history and description of the British Metropolis and its neighbourhood Volume V (1808)

Prosser, George Frederick, Select Illustrations of the County of Surrey (1828)