|

Staircase of the British Museum in Montagu House

Watercolour by George Scharf I (1845)

© Trustees of the British Museum |

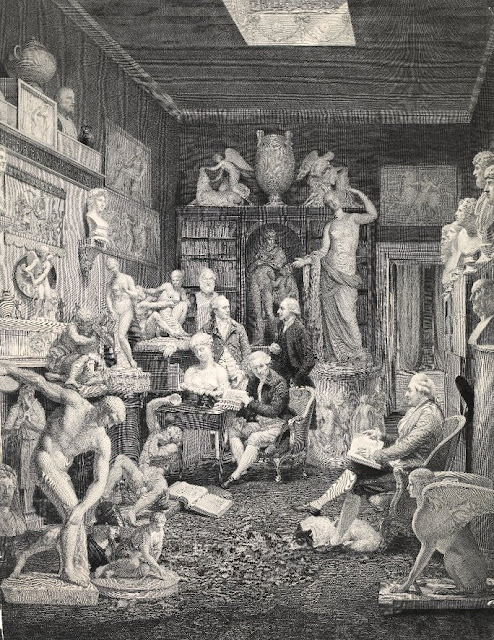

Sir Hans Sloane’s collection

The British Museum was founded on 7 June 1753 by an Act of Parliament, becoming the first national public museum in the world. It was established as a result of accepting the bequest of the physician and naturalist, Sir Hans Sloane, who left the entire contents of his collection to George II in return for a payment of £20,000 to the beneficiaries of his will.

Sloane’s collection consisted of over 71,000 objects including books, manuscripts, natural specimens and antiquities such as coins, medals, prints and drawings.

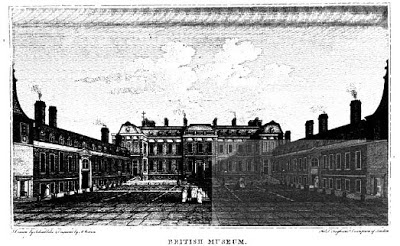

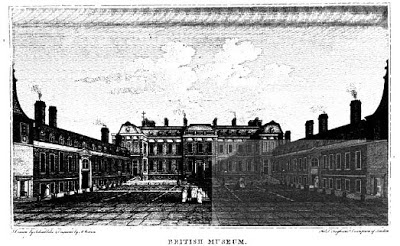

Montagu House

|

The North Front of Montagu House and Gardens

An engraving by James Simon (1714)

© Trustees of the British Museum |

In 1755, the Trustees of the British Museum bought Montagu House in Bloomsbury to house the museum’s collections. The gardens were opened to the public from 11 March 1757 and the museum was opened to the public for the first time on 15 January 1759.

In 1823, Sir Robert Smirke designed a new building to display the growing collections, consisting of a quadrangle with four wings and Greek style columns. The building was finished in 1852 and is still the centre of the museum complex today.

|

| The British Museum(2014) |

The reading room

According to a guidebook for 1800:

Such literary gentlemen as desire to study in it, are to give in their names and places of abode, signed by one of the officers, of the committee; and if no objection is made, they are permitted to peruse any books or manuscripts which are brought to them by the messenger, as soon as they come to the reading room, in the morning at nine o’clock; and this order lasts six months, after which they may have it renewed. There are some curious manuscripts, however, which they are not permitted to peruse, unless they make a particular application to the committee, and then they obtain them; but they are taken back to their places in the evening, and brought again in the morning.1

The curiosities

Entry was free and granted to “all studious and curious Persons.”

2

The 1800 guidebook describes the admission process:

Those who come to see the curiosities, are to give in their names to the porter, who enters them in a book, which is given to the principal librarian, who strikes them off, and orders the tickets to be given in the following manner: In May, June, July and August, forty-five are admitted on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, viz. fifteen at nine in the forenoon, fifteen at eleven, and fifteen at one in the afternoon. On Monday and Friday fifteen are admitted at four in the afternoon, and fifteen at six. The other eight months in the year, forty-five are admitted in three different companies, on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, at nine, eleven and one o’clock.1

|

An entrance ticket to the British Museum (1790)

© Trustees of the British Museum |

According to the British Museum’s website, visitors were taken round the exhibition by an under-librarian in groups of five, up the great staircase, through the upper rooms and down again to the ground floor.

A guidebook for 1803-4 says:

All fees are prohibited, and persons who wish to view the Museum must previously enter their names and address, and the time when they would wish to see it, in a book kept by the porter. On a future day they will be supplied with tickets free of expense. Children are not admitted.3

|

Entrance of the British Museum

from Russell Street; Garden front (1761)

© Trustees of the British Museum |

Various opening arrangements were adopted over the years, but by 1809, it seems that entry was no longer by ticket. The museum was open on Monday, Wednesday and Friday from 10am to 4pm and “all persons of decent appearance who apply between the hours of ten and two, are immediately admitted.”4

It was closed for Christmas, Easter and Whitsun weeks and during the months of August and September. People could stay until closing time if they wished, though children under ten were still excluded. According to Leigh's London guide, these arrangements were still in force in 1818.

|

The British Museum

from London; being an accurate history and description

of the British Metropolis and its neighbourhood Volume IV

by David Hughson (1807) |

The arrangement of the collections

Initially the collections were split into three sections: printed books and prints; manuscripts including medals; and natural and artificial productions - basically, anything else.

By 1809, this had been separated into four: printed books; manuscripts; natural history and modern artificial curiosities; antiquities, coins, drawings and engravings.3

They were arranged over the rooms of Montagu House in these sections:

Lower floor: Library of printed books

Upper floor: modern works of art; manuscripts; minerals; shells, fossils & herbals; insects, worms, corals & vegetables; birds & quadrupeds, stuffed; quadrupeds, snakes, lizards, and fishes, in spirits.

Gallery: terra cottas; Greek & Roman sculptures; Roman sepulchral antiquities; Egyptian antiquities; coins & medals; Sir William Hamilton’s collection; drawings & engravings.

The growth of the museum

During the 1850s and beyond, the museum expanded its collections to include British and medieval antiquities, oriental art, prehistoric finds and archaeological material from Europe.

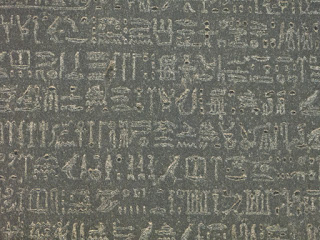

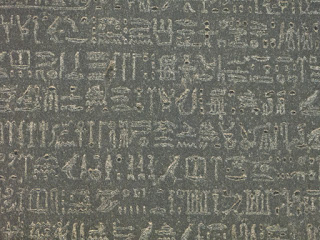

The museum was involved in excavation abroad – its Assyrian collections helped the understanding of an ancient Middle Eastern script called cuneiform and the Rosetta Stone unlocked the meaning of Egyptian hieroglyphic script.

In the 1880s, the natural history collections were moved to a new building in South Kensington. This became the Natural History Museum.

|

Close-up of the Rosetta Stone

in the British Museum (2014)

|

The exhibits

The museum’s collections included:

• The Cottonian library of books and manuscripts (early 1750s)

• The Harleian collection of manuscripts (early 1750s) – purchased by parliament for £10,000

• The first ancient Egyptian mummy (1756)

• Various ethnographic artefacts from Captain Cook’s Pacific voyages, including a Tahitian mourner’s dress (1756)

• The “Old Royal Library” of the sovereigns of England – donated by George II (1757)

• The trunk of a tree gnawed by a beaver (1760)

• A stone resembling a petrified loaf (1760)

• Italian antiquities (1762) – £8410

• A live tortoise from North America (1765)

• Gustavus Brander’s fossils (1765)

• Birch’s library (1766)

• Greenwood's collection of stuffed birds – from Holland (1769) - £460

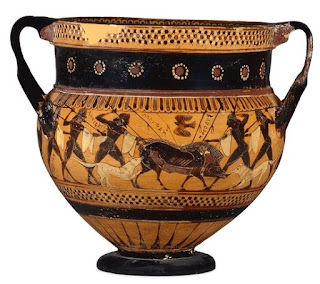

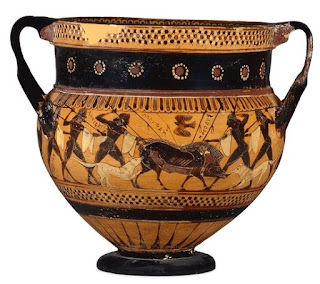

• Sir William Hamilton’s collection of Greek vases (1772) – Etruscan, Grecian and Roman antiquities - £8400

|

The 'Hunt krater' (575-550BC)

from Sir William Hamilton's collection

© Trustees of the British Museum |

• Halhed’s oriental manuscripts (1796)

• Hatchett’s minerals (1798) - £700

• Tysson’s Saxon coins (1802)

• The Rosetta Stone (1802)

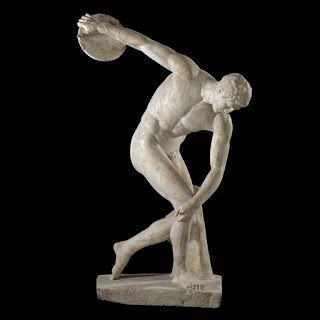

• The Townley collection of classical sculpture including the “Discobolus” statue and the bust of a young woman “Clytie” (1805).

You can read more about Charles Townley here.

• Lansdown manuscripts (1807) - £4,925

• Bentley’s classical library (1807)

• Roberts’ coins (1810)

• Greville minerals (1810) - £13,727

• Hargrave library (1813) - £8,000

• Sculptures from the Temple of Apollo at Bassae (1815)

• The Parthenon sculptures (1816)

|

Some of the Parthenon sculptures in the British Museum (2014)

|

• George III’s library (1823) – donated by George IV; the quadrangular building was erected to house it.

• Western Asiatic collection began – manuscripts, medals and antiquities (1825)

• The Nereid monument (1842)

• First stone sculptures from excavations at Nimrud site in the Middle East including the great winged bull (1850s)

• The remains of the Mausoleum of Halikarnassos (1856-7)

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) From Scatcherd's Ambulator (1800)

(2) The British Museum website

(3) From Crosby's A View of London (1803-4)

(4) From Hughson's London Volume VI (1809)

Sources used include:

Cox, Son and Baylis (publishers), Synopsis of the contents of the British Museum (1809)

Crosby, B , A View of London; or the Stranger's Guide through the British Metropolis (Printed for B Crosby, London, 1803-4)

Hughson, David, London; being an accurate history and description of the British Metropolis and its neighbourhood Volume IV (1807, London)

Hughson, David, London; being an accurate history and description of the British Metropolis and its neighbourhood Volume VI (1809, London)

Leigh, Samuel, Leigh's New Picture of London (London, 1818)

Scatcherd, J, Ambulator or A Pocket Companion in a tour round London (Printed for J Scatcherd, London, 1800)

The British Museum website

All photographs © RegencyHistory.net