|

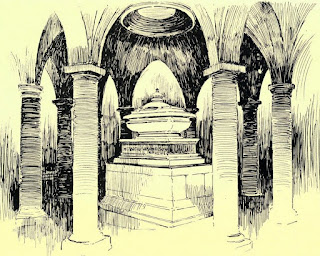

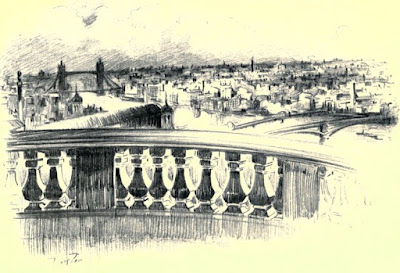

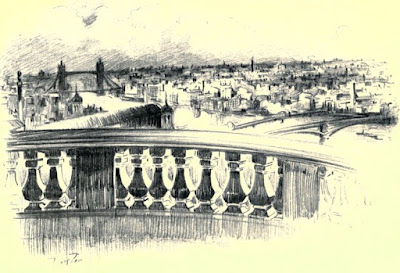

St Paul's Cathedral from The Monuments and Genii

of St Paul's Cathedral and of Westminster Abbey by GL Smyth (1826) |

Profile

St Paul’s Cathedral has been one of London’s iconic landmarks since Georgian times. Designed by Sir Christopher Wren, it served both as a place of worship and a tourist attraction in Regency London, as it continues to do today.

|

| St Paul's Cathedral (Feb 2008) © Andrew Knowles |

History

In 1666, the Great Fire of London destroyed the old medieval cathedral on the site of St Paul’s, along with thousands of other buildings in London. Sir Christopher Wren designed the new cathedral, but what is not widely known, is that it was not built to his original and preferred design.

He first formed a model in wood, according to the best style of Greece and Rome, which was highly approved by persons of superior taste and judgment; but the bishops thought proper to reject it, as not being sufficiently adapted to the usual form of Christian churches.1

Wren altered his design to an acceptable form and the first stone was laid on 21 June 1675, not by Wren himself as some Georgian guidebooks claimed, but by Thomas Strong, the chief mason, and John Longland, the master carpenter. The building was finished 35 years later, in 1710, and the last stone on the top of the lantern was placed by Christopher Wren’s son. The decorations were completed in 1723. The cost was largely financed by a coal tax levied on fuel entering the Port of London.

In 1769, the cathedral was artificially protected from lightning as recommended by the Royal Society.

|

| St Paul's Cathedral (Jun 2015) © Andrew Knowles |

Services at St Paul’s Cathedral

The Picture of London for 1810 said:

St Paul’s is open for divine service, three times every day in the year—at six o’clock in the morning in summer, and seven in the winter; a quarter before ten o’clock in the forenoon; and a quarter before three o’clock in the afternoon.2

The anniversary of the charity schools

On the first Thursday in June, there was a special service of thanksgiving held at St Paul’s attended by all the children from the charity schools of the metropolis. According to The Picture of London for 1810, about 6,000 children attended, though Old and New London suggested that as many as 8,000 were usually present. The Picture of London said the children formed ‘the grandest and most interesting sight which is to be seen in the whole world.’3

George III comes to St Paul’s

On 23 April 1789,

George III held a grand thanksgiving service at St Paul’s to celebrate his recovery from his first serious bout of mental instability.

|

Thanksgiving service at St Paul's Cathedral

for the recovery of George III from Lady's Magazine (1789) |

An annual concert of sacred music

In the middle of May:

The Anniversary of the Sons of the Clergy is held at St. Paul's, where is performed a fine concert of sacred music, and afterwards there is a dinner at Merchant Taylor's Hall. Tickets are to be had of various booksellers.4

Old and New London added that this occasion

… when the choirs of Westminster and the Chapel Royal sing selections from Handel and other great masters, is also a day not easily to be forgotten, for St Paul's is excellent for sound, and the fine music rises like incense to the dome.5

Robbery in 1810

Old and New London noted that only one robbery had occurred in modern times. In December 1810

… the plate repository of the cathedral was broken open by thieves, with the connivance of, as is supposed, some official, and 1,761 ounces of plate, valued at above £2,000, were stolen. The thieves broke open nine doors to get at the treasure, which was never afterwards heard of.6

Sydney Smith at St Paul’s

The English wit and writer Sydney Smith (1771-1845) was appointed canon residentiary of St Paul’s in 1831. This post required him to be in residence for three months a year.

The chief ornament of London

|

| St Paul's Cathedral (Aug 2013) © Andrew Knowles |

The Microcosm of London wrote:

The general form of St Paul’s Cathedral is a long cross; the walls are wrought in rustic, and strengthened, as well as ornamented, by two rows of coupled pilasters; the lower is Corinthian, and the upper composite.7

According to Crosby’s A View of London:

It is built of Portland-stone in the form of a cross; and over the space, where the lines of that figure intersect each other, is a stately dome; and, on the summit of the dome, is a beautiful lanthorn, adorned with Corinthian columns, and surrounded at its base by a balcony. On the lanthorn rests a gilded ball and cross, the latter of which crowns this part of the ornaments of the edifice.8

The Microcosm of London went on to say:

The west front is graced with a most superb portico, a noble pediment, and two stately turrets; and in the approach to the church through Ludgate-street, the elegant construction of this front, the fine turrets over each corner, and the vast dome behind, combine to form an object of the most impressive grandeur.9

|

| St Paul's Cathedral (Aug 2013) © Andrew Knowles |

The Picture of London for 1810 stated:

The length of this church, including the portico, is 500 feet; the breadth 250; the height, to the top of the cross, 340; the exterior diameter of the dome, 145; and the entire circumference of the building, 2,292 feet.10

Crosby’s A View of London wrote:

A dwarf stone wall, supporting an elegant ballustrade of cast iron, surrounds the church, and separates the church-yard or area from a spacious carriage-way on the south side, and a broad foot pavement on the north. In the west end of this area is a marble statue of Queen Anne, holding a sceptre in one hand and a globe in the other, surrounded with four emblematical figures representing Great Britain, France, Ireland and America.11

The marble statue of Queen Anne was by Francis Bird.

|

Statue of Queen Anne outside St Paul's

Cathedral (Aug 2017) © Andrew Knowles |

|

The cathedral was widely admired.

The Picture of London for 1810 claimed:

The chief ornament of London is the Cathedral Church of St Paul, which stands on the northern bank of the Thames, in the centre of the metropolis, on an eminence situated between Cheapside on the east and Ludgate-street on the west.12

Some early Victorian tourists wrote:

St Paul's Cathedral is the most prominent feature in all the views of London, its peculiar cupola or dome catches your eye, look at London from what point you may.13

|

| St Paul's Cathedral (Jul 2012) © Andrew Knowles |

The curiosities of the cathedral

Except when divine service was being held, the doors of the cathedral were kept shut and people had to pay to look around the church and see its curiosities.

The Picture of London for 1810 explained:

Strangers will find admittance by knocking at the northern portico. A person is ready within to pass the visitor to the stair-case leading to the curiosities, for which he demands four-pence … For each of the other curiosities there is a separate charge, and the visitor may see or pass by which of them he pleases.14

Inside the cathedral

|

Interior of St Paul's Cathedral from London; being an accurate history and

description of the British Metropolis and its neighbourhood by D Hughson (1808) |

The body of the church could be seen for two pence.

The Picture of London for 1810 wrote:

The inside of St Paul’s is so far from corresponding in beauty with its exterior, that it is almost entirely destitute of decoration.15

Not everyone agreed that this emptiness detracted from its magnificence. Louis Simond, who visited Great Britain in 1810-11 wrote:

We stopped at St Paul's. My admiration of this magnificent temple is not yet diminished. Its interior is thought naked and unfinished. I was nevertheless struck with its greatness, which loses little by the want of minute ornaments.16

|

Inside of St Paul's Cathedral

from Illustrations of the public buildings

of London by J Britton and A Pugin (1825) |

Sir Christopher Wren had wanted to decorate the inside of the cathedral with mosaic, but this was pronounced too costly. According to

The Microcosm of London,

Sir Joshua Reynolds and other British artists offered to brighten up the inside of the cathedral with a series of pictures, but their offer was declined on the grounds that the Bishop of London at the time did not think such decorations would be ‘consistent with the character of a Protestant church.’

17

The Picture of London for 1810 described the church:

The entire pavement, up to the altar, is of marble chiefly consisting of square slabs, alternately black and white; and is very justly admired. The floor round the communion-table is of the same kind of marble mingled with porphyry. The communion table has no other beauty; for, though it is ornamented with four fluted pilasters, that are very noble in their form they are merely painted and veined with gold, in imitation of lapis lazuli. Eight Corinthian columns, of blue and white marble, of exquisite beauty, support the organ gallery. The screen that incloses the choir, is poor in itself, and forms an absurdity, by its Gothic architecture, in the midst of the Grecian style of the stone-work. The reader’s desk is a fine example of its kind; it is composed of an eagle with expanded wings, standing, surrounded with rails, which are of brass and gilt.18

The carvings in the choir were by Grinling Gibbons. The Gothic screen berated by

The Picture of London in the passage quoted above was removed in 1859.

|

Interior of the choir of St Paul's (1754)

from Old and New London by W Thornbury (1873) |

The crypt

The Picture of London for 1810 wrote:

The crypts or vaults of St Paul’s are silent dreary mansions, lighted at distant intervals, by grated prison-like windows, which afford partial gleams of light, long intervals of shade intervening. The vast piers and immense arches divide the vaults into three avenues.19

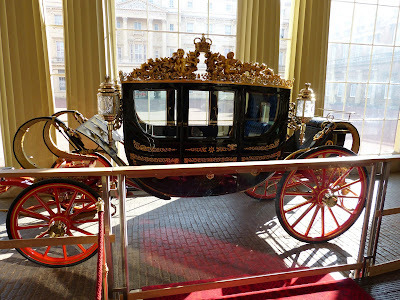

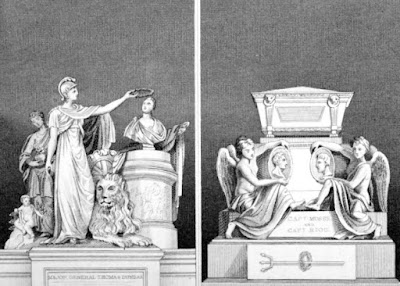

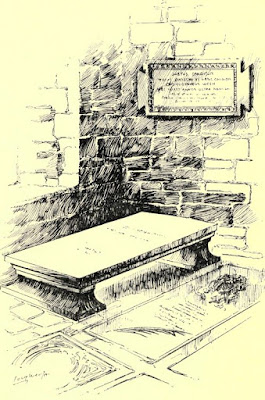

Sir Christopher Wren was laid to rest in the crypt of St Paul’s. The Microcosm of London wrote:

His remains were interred in the great vault of his own church: a common stone covers the grave.20

On the wall above the grave is an inscription that ends with the words:‘Lector, Si monumentum requiris, circumspice’.20 Translated this means: “Reader, if you seek a monument, look about you.”

Old and New London wrote:

He lies in the place of honour, the extreme east of the crypt. The black marble slab is railed in, and the light from a small window-grating falls upon the venerated name.21

|

Sir Christopher Wren's tomb from Memorials

of St Paul's Cathedral by WM Sinclair (1909) |

Many celebrated Regency era artists now lie in the crypt near Wren – Sir Joshua Reynolds, Benjamin West, John Opie,

Sir Thomas Lawrence and Joseph Mallord William Turner.

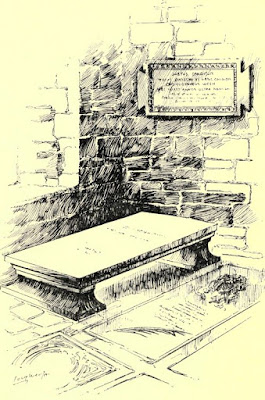

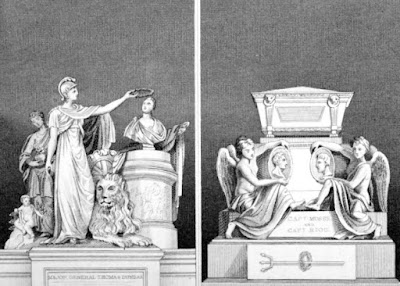

Statues and memorials

When St Paul’s was first built, it was completely devoid of statues and memorials. It was only when Westminster Abbey became too overcrowded that it was agreed to start erecting monuments in the cathedral. The first statue was of the philanthropist and prison reformer John Howard (1726-1790), followed by the lexicographer Dr Samuel Johnson (1709-1784). Both statues were carved by John Bacon.

|

Monuments to John Howard (left) and Dr Samuel Johnson (right)

in St Paul's Cathedral from The Monuments and Genii

of St Paul's Cathedral and of Westminster Abbey by GL Smyth (1826) |

The Picture of London for 1810 mentioned a third statue, to the memory of

… Sir William Jones, a man whose study it was to make the British name honoured and revered among the natives of the East Indies.22

A statue was later erected to the memory of

Sir Joshua Reynolds, sculpted by John Flaxman.

|

Monument to Sir Joshua Reynolds in

St Paul's Cathedral from The Monuments

and Genii of St Paul's Cathedral and of

Westminster Abbey by GL Smyth (1826) |

Military heroes were also commemorated in St Paul’s. The Picture of London for 1810 noted that:

… monuments have been erected to the memory of Captains Burgess, Faulkner, Westcott, Riou, and Moss, and General Dundas, who fell in the last war, gloriously fighting in their country’s cause.22

|

Monuments to Major General Dundas (left) and Captains Moss and

Riou (right) in St Paul's Cathedral from The Monuments and Genii

of St Paul's Cathedral and of Westminster Abbey by GL Smyth (1826) |

The Picture of London for 1810 also recorded that:

In this part of the cathedral the spectator will be struck with the appearance of a number of tattered flags, the trophies of British valor.22

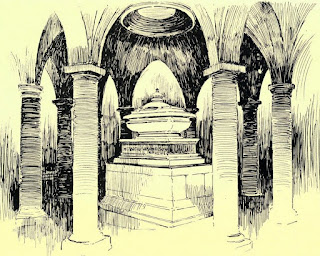

Vice Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson

|

Horatio Nelson's tomb from Memorials

of St Paul's Cathedral by WM Sinclair (1909) |

The hero of the Battle of Trafalgar,

Vice Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson, was interred at St Paul’s Cathedral on 9 January 1806 after a four-hour funeral service. According to

Old and New London:

Nelson's coffin was formed out of a mast of the L'Orient—a vessel blown up at the battle of the Nile … The sarcophagus, singularly enough, had been designed by Michael Angelo's contemporary, Torreguiano, for Wolsey … Nelson's flag was to have been placed over the coffin, but as it was about to be lowered, the sailors who had borne it, as if by an irresistible impulse, stepped forward and tore it in pieces, for relics.23

|

Horatio Nelson's tomb from Memorials

of St Paul's Cathedral by WM Sinclair (1909) |

Simond recorded his observations of Nelson’s final resting place:

Through an iron grate in the pavement under the dome, we observed a light. It is a sepulchral vault, where the remains of the naval hero of England have been deposited.24

The Picture of London for 1810 noted that it is intended to erect a superb monument to his memory.25 The Picture of London for 1818 recorded that ‘this monument is just finished.’26

|

Monument erected in St Paul's Cathedral to

the memory of Nelson from the European

Magazine and London Review (1818) |

The Duke of Wellington

The hero of the Battle of Waterloo,

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, was also interred at St Paul’s with great pomp and ceremony. His funeral was held on 18 November 1852 and the enormous monument erected to his memory took decades to complete.

|

Wellington memorial in St Paul's

Cathedral from A history of

England by HO Arnold-Forster (1913) |

The cathedral library

For two pence, visitors could choose to see the library:

It is a handsome room, about fifty feet by forty, having shelves of books to the top, with a gallery running along the sides. The floor is of oak, consisting of 2,376 in small square pieces, and is not only curious for its being inlaid, without a nail or peg to fasten the parts, but is extremely neat in the workmanship, and very beautiful in its appearance. The collection of books is neither large nor very valuable.27

According to Old and New London:

The room contains some loosely hung flowers, exquisitely carved in wood by Grinling Gibbons.28

|

The library of St Paul's Cathedral

from Old and New London by W Thornbury (1873) |

The geometrical staircase

At the end of the gallery is a geometrical staircase of 110 steps, which was constructed by Wren to furnish a private access to the library.28

The Picture of London for 1802 stated:

The geometrical stair-case is a very noble flight of steps of stone; and, although the principle on which it is erected is generally known, this stair-case well deserves to be seen. The charge for this is two-pence.29

The model

For another two pence, visitors could see the model of Sir Christopher Wren’s original design for the cathedral which had cost £600 to make.

The beautiful model, formed under the direction of Sir Christopher Wren, from his first design of this cathedral, must be gratifying to every man of taste, who will naturally regret, that it was not preferred to the model on which the church is built.30

The clock-work and Great Bell

|

The clockwork of St Paul's Cathedral from Memorials

of St Paul's Cathedral by WM Sinclair (1909) |

The Picture of London for 1810 stated:

The Clock-work and Great Bell, are to be seen for two-pence. The former is curious, both for the magnitude of its wheels and other parts, and the very great accuracy and fineness of its workmanship. The length of the pendulum is fourteen feet, and the weight at the extremity 1 cwt. [We recommend strangers, if possible, to visit this part of the cathedral between the hours of twelve and one, as at that time the man who superintends the clock, to wind it up, will be on the spot to afford any assistance, and give the proper explanations. The spectator will do well to take a survey of the streets from this place before he ascends to the upper galleries.]

|

The Great Paul bell from Memorials

of St Paul's Cathedral by WM Sinclair (1909) |

The Great Bell, in the southern tower, weighs 11,470 lbs. The hammer of the clock strikes the hours on this bell, which may be heard at a great distance, and is uncommonly fine in its tone. The great bell is never tolled but on the death of the king, queen, or some of the royal family; or for the bishop of London; or for the dean of St Paul’s; and, when tolled, the clapper is moved and not the bell.31

The Whispering Gallery

|

St Paul's Cathedral from

The Microcosm of London (1808-10) |

For another two pence, visitors could visit the Whispering Gallery:

The Whispering gallery is a very great curiosity. It is 140 yards in circumference. A stone seat runs round the gallery, along the foot of the wall. On the side directly opposite the door by which the visitor enters, several yards of the seat are covered with matting, on which the visitor being seated, the man who shews the gallery, whispers, with his mouth close to the wall, near the door, at the distance of 140 feet from the visitor, who hears his words in a loud voice, seemingly at his ear. The meer shutting of the door produces a sound, to the visitor on the opposite seat, like violent claps of thunder. The effect is not so perfect if the visitor sits down half way between the door and the matted seat [and still less so if he stands near the man who speaks, but on the other side of the door].32

The paintings on the inside of the dome depicted eight scenes from the life of St Paul and were painted by Sir James Thornhill. An early Victorian tourist wrote:

The best place inside to view the paintings and the interior of the dome is from the Whispering Gallery; here if the door is shut it resembles thunder, and a low whisper breathed against the wall can be most distinctly heard on the opposite side of this immense circle by placing your ear against the wall.33

The Picture of London for 1810 noted:

These paintings are now running to decay; but, as they may be replaced by something infinitely more valuable, that is not to be lamented.34

The viewing galleries and the ball or lantern

|

The Stone Gallery from Memorials

of St Paul's Cathedral by WM Sinclair (1909) |

The cost of visiting the two outside viewing galleries of St Paul’s – the lower stone gallery and the upper golden gallery – was included in the four pence entrance fee to the curiosities, but there was an additional cost for those adventurous enough to ascend to the ball or lantern.

For this first cost, the visitor passes to the two galleries on the outside of the church, the first being on the top of the collonade, and the highest at the foot of the lanthorn. Many persons pay no more than this first charge, (four-pence) and amuse themselves by the prospect from either, or both of the galleries.35

The metropolis, when viewed from the gallery at the foot of the lanthorn, presents a most curious scene, in which the streets, the pavement, the carriages, and foot-passengers, appear, as it were, in miniature. Indeed, the form of the metropolis and the circumjacent country, is most perfectly seen from this gallery, on a fine summer’s day.36

|

| St Paul's Cathedral (Jun 2015) © Andrew Knowles |

The Ball is to be seen for one shilling and six pence for each person; and one shilling over and above is paid to the guide; so that, if only one person ascends to the ball, it is at the expenses of two shillings and sixpence; if more than one, the guide having no more than one shilling, the expense to each is lessened in proportion to the number. The ascent to the ball is attended with some difficulty, and is encountered by few; yet, both the ball and passage to it well deserve the labour. The diameter of the interior of the ball, is six feet two inches; and it will contain twelve persons.37

Anyone who wishes may climb up from there [the Whispering Gallery] to the so-called lantern, the glass sphere situated just above the dome. A superb panorama of the whole of London, its suburbs and environs can be enjoyed from there. However, a mild day and a time when the city is least obscured by smoke should be chosen.38

From the bottom of the whispering gallery are 280 steps, including those to the golden gallery are 534 and to the ball, in all, are 616 steps.39

|

| View from St Paul's Cathedral (Jun 2015) © Andrew Knowles |

Mr Horner’s panorama

In 1822 Mr Horner passed the summer in the lantern, sketching the metropolis; he afterwards erected an observatory several feet higher than the cross, and made sketches for a panorama on a surface of 1,680 feet of drawing paper. From these sheets was painted a panorama of London and the environs, first exhibited at the Colosseum, in Regent's Park, in 1829. The view from St Paul's extends for twenty miles round.40

What can you see today?

St Paul’s Cathedral is still a popular tourist attraction today. Much of the cathedral is unchanged, but there are some notable differences.

• A whiter cathedral - the façade would have been much blacker in the Regency period, having been darkened by 100 years of smoke pollution. The outside was cleaned as part of a 15-year restoration project that was completed in 2011.

• Lots more statues and monuments, such as the huge memorial to the Duke of Wellington mentioned above.

• Lots of Victorian embellishments, such as the altar and mosaic decorations above the choir area.

• Holman Hunt’s painting The Light of the World, presented to the cathedral in 1908.

Last visited outside August 2017 and inside June 2015.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) From Ackermann, Rudolph and Combe, William, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 3 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904).

(2) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(3) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810)

(4) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810)

(5) From Thornbury, Walter, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 1.

(6) From Thornbury, Walter, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 1.

(7) From Ackermann, Rudolph and Combe, William, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 3 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904).

(8) From Crosby, B, A View of London; or the Stranger's Guide through the British Metropolis (Printed for B Crosby, London, 1803-4).

(9) From Ackermann, Rudolph and Combe, William, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 3 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904).

(10) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(11) From Crosby, B, A View of London; or the Stranger's Guide through the British Metropolis (Printed for B Crosby, London, 1803-4).

(12) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(13) From Nowrojee, Jehangeer, Jahangir, Nauroji and Merwanjee, Hirjeebhoy, Journal of a Residence of Two Years and a Half in Great Britain (1841).

(14) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(15) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(16) From Simond, Louis, Journal of a Tour and Residence in Great Britain, during the years 1810 and 1811 vol 1 (1815).

(17) From Ackermann, Rudolph and Combe, William, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 3 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904).

(18) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(19) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(20) From Ackermann, Rudolph and Combe, William, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 3 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904).

(21) From Thornbury, Walter, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 1.

(22) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(23) From Thornbury, Walter, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 1.

(24) From Simond, Louis, Journal of a Tour and Residence in Great Britain, during the years 1810 and 1811 vol 1 (1815).

(25) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(26) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1818 (1818).

(27) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(28) From Thornbury, Walter, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 1.

(29) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1802 (1802).

(30) From Crosby, B, A View of London; or the Stranger's Guide through the British Metropolis (Printed for B Crosby, London, 1803-4).

(31) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(32) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1807 (1807).

(33) From Nowrojee, Jehangeer, Jahangir, Nauroji and Merwanjee, Hirjeebhoy, Journal of a Residence of Two Years and a Half in Great Britain (1841).

(34) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(35) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(36) From Crosby, B, A View of London; or the Stranger's Guide through the British Metropolis (Printed for B Crosby, London, 1803-4).

(37) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(38) From Lach-Szyrma, Krystyn, London Observed, A Polish Philosopher at Large, 1820-24 (2009).

(39) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1813 (1813).

(40) From Thornbury, Walter, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 1.

Sources used include:

Ackermann, Rudolph and Combe, William, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 3 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904)

Bell, Alan, Sydney Smith, a biography (1982)

Crosby, B, A View of London; or the Stranger's Guide through the British Metropolis (Printed for B Crosby, London, 1803-4)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1802 (1802)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1807 (1807)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1809 (1809)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1813 (1813)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1818 (1818)

Hughson, David, London; being an accurate history and description of the British Metropolis and its neighbourhood Volume III (1806)

Lach-Szyrma, Krystyn, London Observed, A Polish Philosopher at Large, 1820-24 (2009)

Nowrojee, Jehangeer, Jahangir, Nauroji and Merwanjee, Hirjeebhoy, Journal of a Residence of Two Years and a Half in Great Britain (1841)

Saunders, Ann, St Paul's Cathedral - 1400 years at the heart of London (2012)

Simond, Louis, Journal of a Tour and Residence in Great Britain, during the years 1810 and 1811 vol 1 (1815)

Thornbury, Walter, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 1

All photographs © RegencyHistory.net