|

| Osterley Park House from across the lake |

Where is it?

Osterley Park is a Neoclassical mansion in Isleworth, Middlesex.

Early history

Sir Thomas Gresham, a merchant and financier, built a Tudor manor house at Osterley in the 1570s. In the late 17th century, the property was owned by Nicholas Barbon, an economist and financial speculator who was involved in the development of fire insurance. On Barbon’s death in 1698, there was an outstanding mortgage on the house owing to Child’s Bank.

|

| Front of the house, Osterley Park |

Sir Francis Child of Child’s Bank

Sir Francis Child the Elder (1642-1713) started out as an apprentice goldsmith and rose to become a partner in the firm, which by then was concentrating on its banking activities. He married his employer’s daughter and inherited the whole business in 1681.

In 1713, Osterley Park passed to Sir Francis Child the Elder in settlement of Barbon's debt to the bank. It was an early case of bank repossession!

|

Detail from View of Temple Bar attributed to John Collett

The premises of Child & Co are immediately to the left

of Temple Bar |

Neoclassical redevelopment

In 1761, Sir Francis Child the Elder’s grandson, also called Francis (1735-63), commissioned Robert Adam to redevelop the house at Osterley in the

Neoclassical style. Francis died suddenly two years later and his brother Robert Child (1739-82) further commissioned Adam to design Neoclassical interiors for the house.

|

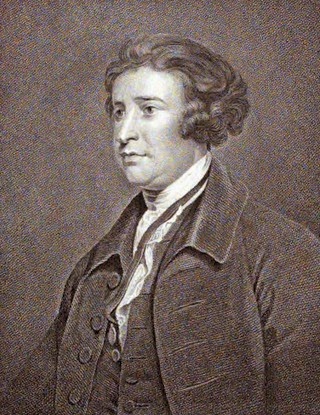

| Francis Child (1735-1763) by Allan Ramsay |

Adam was responsible for the total design of Osterley – from the magnificent portico to the patterns on the ceilings and the designs for the furniture. He also designed garden buildings such as the Garden House, the Orangery (no longer standing) and the Temple of Pan. Adam’s work at Osterley spanned from 1761 to 1779 and many of his designs have been preserved at the Sir John Soane’s Museum in London.

|

| Inside the Temple of Pan in the garden, Osterley Park |

The runaway bride

Robert Child and his wife Sarah Jodrell were extremely wealthy. As well as Osterley, they had a house in Berkeley Square in London and a hunting lodge in Warwickshire. They lived in their Neoclassical show home at Osterley Park from May to November. They had one child, a daughter Sarah Anne (1764-1793).

John Fane, 10th Earl of Westmorland, asked to marry Sarah Anne, but Robert refused. Robert wanted his heir to take the Child name and also feared that his fortune would be squandered by the Earl who was known as ‘Rapid Westmorland’ because of his gambling habit. The Earl of Westmorland took matters into his own hands and eloped with Sarah Anne. They were married on 20 May 1782 at Gretna Green.

Robert Child was so angry that he cut his daughter out of his will, leaving Osterley Park and his entire fortune to Sarah Anne’s second son or eldest daughter provided that they took the name Child.

|

Robert and Sarah Child and their daughter Sarah

Anne by Margaret Battine after Daniel Gardner

Portrait originally created in 1781 |

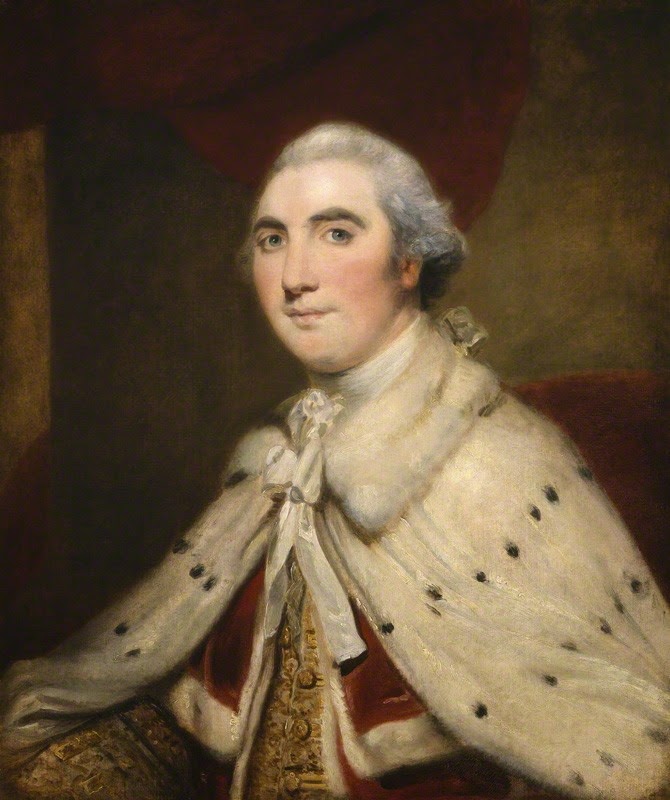

Lady Jersey

Sarah Anne had only one surviving son and so Robert Child’s fortune passed to her eldest daughter, Sarah Sophia Fane, who married George Villiers, later 5th Earl of Jersey.

Lady Jersey was a leading figure in Regency society and was a patroness of

Almack's Assembly Rooms. The Earl of Jersey added the name Child to his own in 1819.

|

| Sarah Sophia Fane - Countess of Jersey |

Given to the National Trust

Osterley Park proved expensive to maintain, but it stayed in the family until 1949 when the 9th Earl of Jersey gave the house and grounds to the

National Trust.

|

| Front of the house, Osterley Park |

Adam's magnificent portico

|

| Front entrance of the house, Osterley Park |

|

| The ceiling of Adam's pillared portico, Osterley |

The Entrance Hall

The panels in the alcoves look three-dimensional, but they are in fact just paintings – a convincing example of trompe-l’œil. The fireplaces are made of Portland stone and display the Child family crest of an eagle with an adder in its mouth.

|

| The Entrance Hall, Osterley |

|

| The Entrance Hall, Osterley |

The Eating Room

Gate-leg tables were kept in the adjacent corridors and brought in as required for mealtimes. The pedestals on either side of the sideboard open and could be used to hide away a chamber pot.

|

| The Eating Room, Osterley |

|

| The Eating Room, Osterley |

|

| One of the pedestals in the Eating Room, Osterley |

|

Detail of one of the pedestals

in the Eating Room, Osterley |

The Long Gallery

|

| The Long Gallery, Osterley |

|

| The Long Gallery, Osterley |

The Drawing Room

|

| The ceiling in the Drawing Room, Osterley |

The ceiling design is cleverly reflected in the carpet.

|

| The Drawing Room, Osterley |

The Tapestry Room

The chairs were upholstered to match the tapestries.

|

| The Tapestry Room, Osterley |

The State Bedchamber

This bed was designed to impress rather than to be slept in. It is an eight-poster bed; there are two posts at each corner. The domed roof of the bed is beautifully decorated, both inside and out.

|

| The State Bedchamber, Osterley |

|

View inside the canopy above the state bed

in the State Bedchamber, Osterley |

The Etruscan Dressing Room

Adam’s inspiration for this room came from Sir William Hamilton’s collection of Etruscan vases.

|

| The Etruscan Dressing Room, Osterley |

|

| The ceiling of the Etruscan Dressing Room, Osterley |

The Library

The books in the library are representative rather than belonging to the family. Francis Child’s book collection had to be sold in the late 19th century in order to pay for repairs to the house.

|

| The Library, Osterley |

|

| The Library, Osterley |

The Great Stair

|

| The Great Stair, Osterley |

|

| Detail from one of the pillars of the Great Stair, Osterley |

Mr Child's Bedchamber

The room used by Robert and Sarah Child when they lived at Osterley.

|

| Mr Child's Bechamber, Osterley |

Mr Child's Dressing Room

|

| Mr Child's Dressing Room, Osterley |

Mrs Child's Dressing Room

|

| Mrs Child's Dressing Room, Osterley |

The Yellow Taffeta Bedchamber

|

| The Yellow Taffeta Bedchamber, Osterley |

The Steward’s Room

|

The Steward's Room

As left by the Earl of Jersey in the 1970s |

Mrs Bunce’s Room

Mr Bunce was the steward at Osterley in the late 18th century and he was assisted by his wife, Mrs Bunce. The photograph shows the safe which was installed in the 19th century.

|

| Mrs Bunce's Room, Osterley |

The Sun Room

I have called this little room the sun room, but it is not listed in my guidebook. It is decorated in the Etruscan style and could be accessed through the house downstairs when I visited in August 2014.

|

| The Sun Room, Osterley |

The rear view of the house

|

| The rear view of the house, Osterley |

|

| The rear view of the house, Osterley |

|

| The back door of the house, Osterley |

The Garden Room

|

| The Garden Room in the gardens at Osterley |

The Temple of Pan

|

| The Temple of Pan in the gardens at Osterley |

Last visited June 2022.

Rachel Knowles writes faith-based Regency romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Sources used include:

Evans, Sian,

Osterley Park and House (National Trust 2009)

All photos © Andrew Knowles & RegencyHistory.net