Don’t read this book unless you are prepared to become emotionally involved with the lives of people who died 200 years ago.

God Save the King was re-released as Queen of Bedlam in 2014.

|

| Blue plaque about Mary Anning outside Lyme Regis museum (2013) |

A few days ago, immediately after the late high tide, was discovered, under the cliffs between Lyme Regis and Charmouth, the complete petrification of a crocodile, 17 feet in length, in a very perfect state. It was dug out of the cliff nearly on a level with the sea, about 100 feet below the surface of the earth.1The ichthyosaur was sold to Mr Henley, the lord of the manor, for £23. It was then acquired by William Bullock for his Museum of Natural History in London. When Bullock’s collection was sold in 1819, the British Museum bought it for £47 5s and it then passed to the Natural History Museum when this became a separate entity.

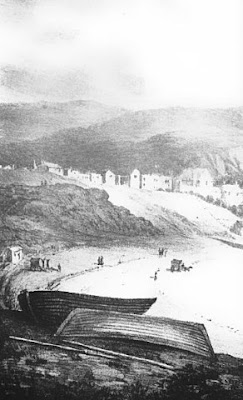

|

| Lyme Regis from The History of Lyme Regis by G Roberts (1823) |

...the persevering industry of a young female fossilist of the name of Hanning of Lyme in Dorsetshire and her dangerous employment.2A plesiosaurus for the Duke of Buckingham

|

| Duria Antiquior by Henry de la Beche (1830) © National Museum of Wales |

...prim, pedantic, vinegar-looking, thin female, shrewd, and rather satirical in conversation.3

Mary Anning’s knowledge of the subject is quite surprising – she is perfectly acquainted with the anatomy of her subjects, and her account of her disputes with Buckland, whose anatomical science she holds in great contempt, was quite amusing.4

|

| The entrance to the Dorset County Museum, Dorchester (2012) |

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

|

| Cheapside from Ackermann's Repository (Jun 1813) |

“I have an excessive regard for Jane Bennet, she is really a very sweet girl, and I wish with all my heart she were well settled. But with such a father and mother, and such low connections, I am afraid there is no chance of it.”

“I think I have heard you say that their uncle is an attorney in Meryton.”

“Yes;” and they have another, who lives somewhere near Cheapside.”

“That is capital,” added her sister, and they both laughed heartily.

“If they had uncles enough to fill all Cheapside,” cried Bingley, “it should not make them one jot less agreeable.”

“But it must very materially lessen their chance of marrying men of any consideration in the world,” replied Darcy.

To this speech Bingley made no answer; but his sisters gave it their hearty assent, and indulged their mirth for some time at the expense of their dear friend’s vulgar relations.1

|

| North side of Grosvenor Square from Ackermann's Repository (Nov 1813) |

She [Jane] then read the first sentence aloud, which comprised the information of their having just resolved to follow their brother to town directly, and of their meaning to dine that day in Grosvenor Street, where Mr Hurst had a house.2

“I hope,” added Mrs Gardiner, “that no consideration with regard to this young man will influence her. We live in so different a part of town, all our connections are so different, and, as you well know, we go out so little, that it is very improbable that they should meet at all, unless he really comes to see her.”3

“Mr Darcy may perhaps have heard of such a place as Gracechurch Street, but he would hardly think a month’s ablution enough to cleanse him from its impurities, were he once to enter it.”4

The ‘east’ and ‘west’ ends of London present a curious contrast with respect to the London season. In the city, trade and commerce flow on in their accustomed channels, unaffected by the vicissitudes of fashion. During the month of August, he who moves in fashionable circles may exclaim, “There is nobody in town!” – an expression which appears ridiculous and affected, amidst the never-ending throngs of Fleet Street or Cheapside. But at that period, in the fashionable streets and squares of the ‘west end’, the expression has force and meaning. There, house after house appears deserted; the windows are closed with funeral-looking shutters; the streets, always more or less stately and quiet, are now silent and lonely; one would think that the inhabitants had fled from the approach of the plague, or of a hostile army.5

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

Sources used include:

Ackermann, Rudolph, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics (1813)

Austen, Jane, Pride and Prejudice (1813, London)

The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, The Penny Magazine (29 April 1837)

|

| A ball at Almack's in 1815 (annotated) from Celebrities of London and Paris by Captain Gronow (1865) |

The personages delineated in the frontispiece are well worthy of notice, both from the position they held in the fashionable world, and from their being represented with great truth and accuracy. On the left, the man with the red face, laughing at Brummell, is Charles, Marquis of Queensberry; the great George himself, the admirable Crichton of the age, comes next, in a dégagé attitude, with his fingers in his waistcoat pocket. His neck-cloth is inimitable, and must have cost him much time and trouble to arrive at such perfection. He is talking earnestly to the charming Duchess of Rutland, who was a Howard, and mother to the present Duke.

The tall man, in a black coat, who is preparing to waltz with Princess Esterhazy, so long ambassadress of Austria in London, is the Comte de St Antonio, afterwards Duke of Canizzaro. He resided many years in England, was a very handsome man, and a great lady-killer, and married an English heiress, Miss Johnson. The stout gentleman waltzing with the Russian ambassadress, Countess, afterwards Princess Lieven, is Baron Neumann, at that time secretary to the Austrian embassy. He was afterwards minister at Florence, and married a daughter of the Duke of Beaufort’s.

We next behold, in a wonderful light green coat, black tights, and a crushed hat, the late Sir George Warrender, the famous epicure, whose name was pronounced by Sir Joseph Copley to be really Sir Gorge Provender. The worthy Baronet is talking to the handsome Comte de St Aldegonde, afterwards a general, and at this period aide-de-camp to Louis Philippe, then Duke of Orleans.

The original sketch was given to Brummell by the artist who executed it; and it was highly prized by the king of the dandies. It was purchased at the sale of his effects in Chapel Street by the person who gave it to me.

|

| Top left: Ball dress (Jun 1815) Top right: Evening dress (Feb 1815) from Ackermann's Repository Bottom left: Evening dress (Apr 1829) Bottom right: Ball dress (Apr 1829) from La Belle Assemblée |

|

| The first quadrille at Almack's c1815 from The Reminiscences and Recollections of Captain Gronow (1889) showing the correct dress for Almack's in 1815 |

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

| Ackermann, Rudolph, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics (various) |

| Bell, John, La Belle Assemblée (John Bell, 1806-1837, London) Chancellor, E. Beresford, Memorials of St. James’s Street and Chronicles of Almack’s (1922) |

| Gronow, Captain RH, Celebrities of London and Paris, being a third series of reminiscences and anecdotes (1865) |

|

| Andrew and Rachel Knowles as "Elizabeth Bennet and Mr Darcy" |

|

| "Not handsome enough to tempt me" by Hugh Thomson from Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen (1894 edition) |

|

| A replica of George III's bathing machine, Weymouth |

|

| Original drawing by Mirabelle Knowles (2012) |

|

| Lyme Park - Pemberley in 1995 BBC adaptation of Pride and Prejudice |

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.