|

| Fanny Boscawen by Allan Ramsay (1749) © Croome Park NT/Lionel Matthews |

Early years

Frances Evelyn Glanville was born on 23 July 1719 at St Clere, near Wrotham, Kent. Frances, known as Fanny, was the only daughter of William Evelyn and his wife Frances Glanville, a great niece of the diarist John Evelyn. Her father took her mother’s name on their marriage by Act of Parliament, at the same time as inheriting her fortune.

Fanny’s mother died in childbirth and her father remarried a few years later. Fanny spent much of her childhood staying with relatives - an aunt, Mrs Gore, who lived at Boxley near Maidstone; at Wotton in Surrey with Sir John Evelyn, the grandson of the diarist, and his wife Anne Boscawen; and with Sir John’s son John and his wife Mary Boscawen, his first cousin, a daughter of Hugh Boscawen, 1st Viscount Falmouth.

Marriage

|

| Admiral Edward Boscawen from the painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds from An Historical Journal of the Campaigns in North America by Captain John Knox (1914) |

When Edward returned after three years active service in the war against Spain, he became MP for Truro and was made captain of the Dreadnought. He resumed his courtship of Fanny and they were married on 11 December 1742. They lived in George Street, Hanover Square, London.

Edward and Fanny were very happy together and had five children: Edward Hugh (1744), Frances (1746), Elizabeth (1747), William Glanville (1749) and George (1758).

Hatchlands Park

|

| Hatchlands Park © A Knowles (2014) |

In 1749, Edward and Fanny bought Hatchlands Park, near Guildford, in Surrey. It was an estate that Fanny had set her heart on some time before. Fanny wrote in her journal on 10th August 1748 that she had ‘made no enquiries, my heart still fixed at Hatchlands.’2

Again, on 23rd November 1748 Fanny wrote:

I shall wait for the charming summons at Englefield Green, where I propose to reside again this summer, Hatchland (which I still think of) being neither sold nor saleable.3

Edward and Fanny spent four happy years at Hatchlands together before Edward was once more called away on active service.

In 1757, they commissioned a new house at Hatchlands with interiors designed by Robert Adam.

|

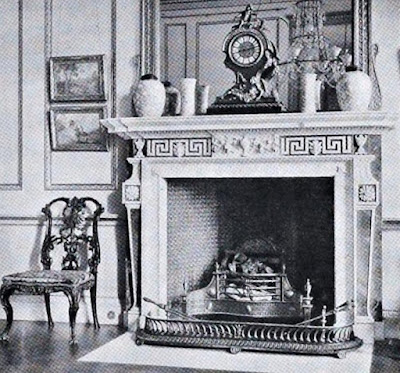

| Adam fireplace in the Drawing Room, Hatchlands from The architecture of Robert and James Adam by AT Bolton (1922) |

Edward’s naval career meant that both during their courtship and after their marriage, Edward and Fanny spent many months apart. Fanny kept a journal to keep Edward in touch with what was happening at home.

Edward proved himself to be a very able naval commander. He was promoted to Rear-Admiral of the Blue in 1747 and appointed Lord Commissioner of the Admiralty in 1751. (Admiral’s wife p146) He rose to Vice Admiral in 1755 and Admiral in 1758. Edward is particularly remembered for his successes in the Siege of Louisburg (1758) and the Battle of Lagos (1759).

Widowhood

Edward died at Hatchlands on 10 January 1761 after an acute attack of typhoid fever. Fanny was distraught. Edward was buried at St Michael Penkevil in Cornwall, in a tomb designed by Robert Adam, and with an inscription written by Fanny herself and ending with the words:

His once happy wife inscribes this marble – an unequal testimony of his worth and of her affection.4

Hre friend Elizabeth Montagu wrote to her husband a week after Edward’s death:

I thank God her mind is very calm and settled; she endeavours all she can to bring herself to submit to this dire misfortune. I know time must be her best comforter, so that I oppose her lamentations rarely and gently, but when they continue long, I set before her the merit of her five children, the want they will have of her, and the comfort she may derive from them.5

Blue-stocking hostess

Edward left his entire fortune to Fanny. She sold Hatchlands and moved back to London, to 14 South Audley Street, where she gained a reputation as an excellent letter writer and conversationalist and became famous for her bluestocking assemblies. Her guests included Elizabeth Montagu, Dr Johnson, Joshua Reynolds, Elizabeth Carter and Hannah More.

I look upon it as a fortunate omen to begin my New Year in Mrs Boscawen’s company. She is in her conversation everything that can make the hours pass agreeably. I must be happier, and I should be better for her friendship.6

|

| Elizabeth Montagu from a print on display in Dr Johnson's House Museum |

In Admiral’s Wife, Cecil Aspinall-Oglander wrote:

Though even Fanny’s dearest friends can never have called her beautiful, her vivacious little face and attractive figure, her level brow and restful wide-apart eyes, her ready wit and subtle understanding, her captivating manner and complete lack of self-consciousness were utterly irresistible.7

Fellow bluestocking Mrs Montagu described Fanny in a letter dated 1757:

She is in very good spirits, and sensible of her many felicities, which I pray God to preserve to her; but her cup is so full of good, I am always afraid it will spill. She is one of the few whom an unbounded prosperity could not spoil. I think there is not a grain of evil in her composition. She is humble, charitable, pious, of gentle temper, with the firmest principles and with a great deal of discretion, void of any degree of art, warm and constant in her affections, mild towards offenders, but rigorous towards offence.8

Hannah More referred to Fanny in this excerpt from her poem, The Bas Bleu; or, Conversation:

Long was society o’er-runBy whist, that desolating Hun;Long did quadrille despotic sit,That Vandal of colloquial wit;And conversation’s setting lightLay half-obscured in Gothic night.At length the mental shades decline,Colloquial wit begins to shine;Genius prevails, and conversationEmerges into reformation.The vanquish'd triple crown to you,Boscawen sage, bright Montagu,Divided, fell; - your cares in hasteRescued the ravag'd realms of Taste.9

|

| Hannah More from Memoirs of the life and correspondence of Mrs Hannah More by William Roberts (1835) |

Losing her beloved husband was not the only loss that Fanny had to bear. Three of her five children died before her: William was drowned in 1769, Edward died in 1774, and Frances Leveson-Gower, to whom she was particularly close, died in 1801. In 1803, her daughter Elizabeth’s husband, Henry Somerset, 5th Duke of Beaufort, also died.

Fanny had a close friendship with her cousin Julia Sayer (née Evelyn) with whom she corresponded regularly until Julia’s death in 1777. Fanny continued to correspond with Julia’s daughter, her god-daughter Frances Sayer, who became her closest companion in the latter years of her life. It was Frances Sayer who collected and saved Fanny’s letters.

Death

Fanny died on 26 February 1805 at her home in South Audley Street, London. She was buried in her husband’s tomb in Cornwall.

The inscription on her grave reads:

Here lie the remains of the Honourable Frances Boscawen, daughter of William Evelyn Glanville Esq of St Clere in the County of Kent and relict of the right Hon Admiral Boscawen to whom she was a faithful and affectionate wife for eighteen years and by whom she had five children, whom she most carefully and tenderly educated: Viz Edward Hugh Boscawen, member of parliament for Truro who died at the spa in Germany July 17th 1774 aged 29 years. Frances, the wife of Rear Admiral the Hon John Leveson Gower who died July 14th 1801 aged 55 years, Elizabeth, married to Henry, 5th Duke of Beaufort who survived her. William Glanville Boscawen who was unhappily drowned at Jamaica 21st April 1769 aged 17 years: A Lieutenant in the Navy and George Evelyn Boscawen third Viscount Falmouth who survived her. Her long and well spent life in the observance of the purest and most exemplary piety and in the practice of every Christian virtue was terminated on the 26th day of February 1805 in London in the 86th year of her age. She was endowed with an uncommon and remarkable strength of understanding and in society, she is thus most truly described by a contemporary author: ‘Her manners are the most agreeable and her conversation the best of any Lady with whom I ever had the happiness to be acquainted.’10

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. Aspinall-Oglander, Cecil, Admiral's Wife, Being the life and letters of The Hon Mrs Edward Boscawen from 1719-1761 (1940)

2. Ibid

3. Ibid

4. Ibid

5. Ibid

6. Ibid

7. Ibid

8. Climenson, Emily J, Elizabeth Montagu, The Queen of the Blue-Stockings Volume 2 (1906)

9. More, Hannah, The Works of Hannah More Volume 5 (1835)

10. Findagrave website - entry for Frances Evelyn Glanville Boscawen

Sources used include:

Aspinall-Oglander, Cecil, Admiral's Wife, Being the life and letters of The Hon Mrs Edward Boscawen from 1719-1761 (1940)

Climenson, Emily J, Elizabeth Montagu, The Queen of the Blue-Stockings Volume 2 (1906)

Eger, Elizabeth, Boscawen (née Glanville), Frances Evelyn (Fanny) (1719-1805), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, online edn 23 Sept 2004)

Eger, Elizabeth, Boscawen (née Glanville), Frances Evelyn (Fanny) (1719-1805), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, online edn 23 Sept 2004)

Knox, Captain John, An Historical Journal of the Campaigns in North America Volume 1 (1914)

All photographs © RegencyHistory.net