The Gordon Riots of 1780

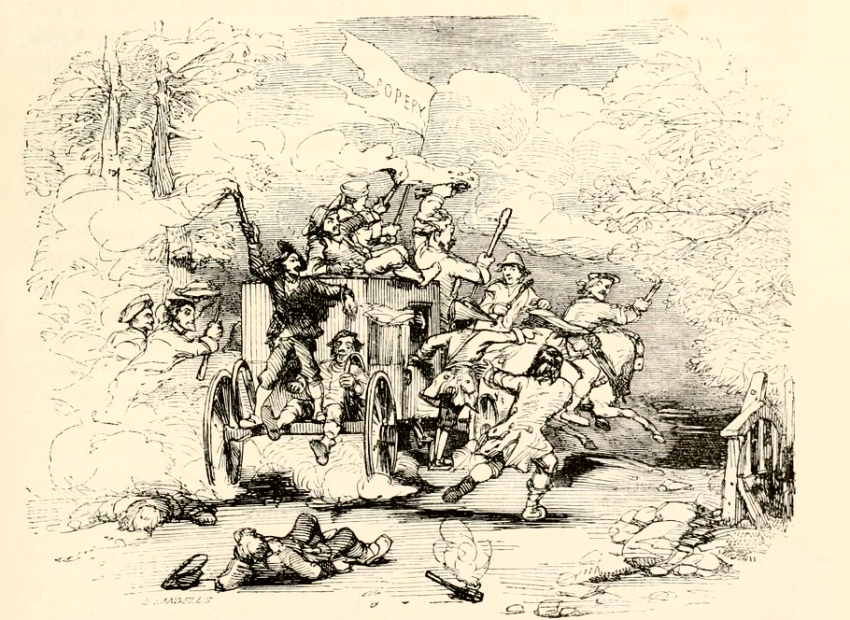

The Gordon Riots from The Chronicles of Crime or The Newgate Calendar by C Pelham illustrated by Phiz (1841)

What were the Gordon Riots?

For a week in June 1780, London experienced some of the worst riots that the city has ever seen. Thousands of anti-Catholic protestors gathered to petition Parliament, but what began as a peaceable religious protest turned into a destructive riot, causing havoc across the city. These became known as the Gordon Riots, after their ringleader, Lord George Gordon.

What caused the Gordon Riots?

The Gordon Riots were an extreme Protestant reaction to the Catholic Relief Act of 1778. The Act relieved some of the discrimination against Catholics including allowing them to join the army. Lord George Gordon, President of the Protestant Society, declared that such a move put British forces in danger should the Catholics turn on their kinsmen and side with Britain’s Catholic enemies instead. He spearheaded a petition for the repeal of the Act.

On Friday 2 June, Lord George, together with some 60,000 protestors, arrived at Parliament to present

… a huge roll of parchment, almost as much as a man could carry, containing the names of those who had signed the petition. 1

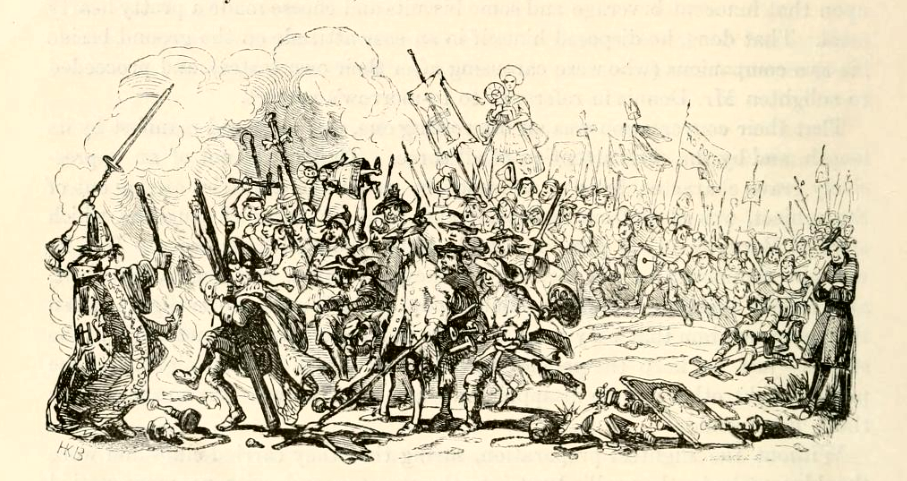

Illustration from Barnaby Rudge by Charles Dickens (1841) which was based on the Gordon Riots

The rabble gets rowdy

Thus far, the protest was peaceable, but it did not remain so. The protestors started attacking the carriages of those arriving at Parliament, who they held responsible for passing the Act.

The protestors

… obliged almost all the members to put blue cockades in their hats, and call out, ‘No Popery!’ Some they compelled to take oath to vote for the repeal of the act. They took possession of all the avenues from the outer door to the door of the House of Commons, which they twice attempted to force open. 2

Lord Chief Justice, Lord Mansfield, had the glasses of his carriage broken and the panels beaten in. The Bishop of Litchfield had his gown torn, and the Duke of Northumberland had his watch stolen. Lord Mansfield’s nephew, Lord Stormont, fared even worse:

They stopped Lord Stormont’s carriage, and great numbers of them got upon the wheels, box, &c taking the most impudent liberties with his Lordship, who was as it were in their possession for near half an hour, and would perhaps not have so soon got away had not a Gentleman jumped into his Lordship’s carriage, and by haranguing the mob persuaded them to desist. 3

Illustration from Barnaby Rudge by Charles Dickens (1841) which was based on the Gordon Riots

Lord George entered the House and presented his petition for ‘A repeal of the Act passed in the last session in favour of the Roman Catholics’, signed by nearly one hundred and twenty thousand people, demanding that it be considered immediately.

The House voted against the immediate consideration of the petition but scheduled it for the following Tuesday, and with the arrival of troops, the crowd was peaceably dispersed.

The riots

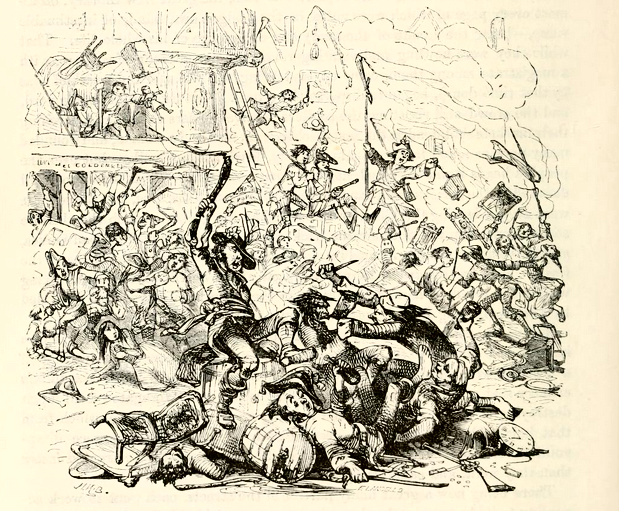

Illustration from Barnaby Rudge by Charles Dickens (1841) which was based on the Gordon Riots

But that was not the end of it. That night, huge numbers of people reassembled and started on a destructive rampage. They destroyed two Catholic chapels, one belonging to the Sardinian ambassador in Duke Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and the other, to the Bavarian ambassador in Warwick Street, near Golden Square.

Thirteen of the perpetrators were arrested and three of the most notorious were incarcerated in Newgate Prison.

The violence continued as the rioters targeted both prominent Catholics and those responsible for making and upholding the law. One of the first homes to be destroyed was that of Sir George Savile who had been responsible for instigating the hated Catholic Relief Bill. The iron railings of his house became the mob’s chief weapons.

The Bow Street offices and home of Sir John Fielding were likewise attacked, as were the shops of Mr Rainsforth, the king’s tallow chandler, and Mr Maberly for bringing evidence against the rioters.

Lord Mansfield’s house destroyed

Lord Mansfield from a miniature at Kenwood House (2019)

Perhaps the worst of the protestors’ anger was directed at Lord Chief Justice, Lord Mansfield. They ransacked his home in Bloomsbury Square.

The furniture, his fine library of books, invaluable manuscripts, containing his lordship's notes on every important law case for near forty years past … were by the hands of these Goths committed to the flames; Lord and Lady Mansfield with difficulty eluded their rage, by making their escape through a back door, some minutes before the savages broke into, and took possession of his house. So great was the vengeance with which they menaced him, that, if report may be credited, they had brought a rope with them to have executed him: and his preservation may be properly termed providential. 4

A group of rioters went out to Hampstead to similarly destroy Kenwood House, Lord Mansfield’s country residence. They were not successful. A guard was there before them and the rioters were diverted by being plied with free ale at nearby Spaniards Inn.

Spaniards Inn, Hampstead (2019)

Prisons and property under attack

Spurred on by alcohol, the rioters continue to cause havoc for several days. They attacked the property of wealthy Catholics, destroying houses, chapels and businesses including Irish merchant James Malo’s house and Mr Langdale’s Holborn distillery.

The mob attacked Newgate Prison and released the prisoners before burning it to the ground. The Clink Prison and the Fleet Prison suffered similar fates whilst other prisons were severely damaged.

Attempts were made on Prime Minster Lord North’s house in Downing Street and the Bank of England, but these were unsuccessful.

Illustration from Barnaby Rudge by Charles Dickens (1841) which was based on the Gordon Riots

Why did it take so long to stop the riots?

Lord Shelburne was not alone in thinking that Parliament had failed to take preventative measures against the possibility of mob violence. He complained that though

… notice was given to the ministry, that a large body was to assemble in St George's-fields, no measure, no precaution was made use of to stem the torrent of outrage, which might be expected to join those who had too much religion, tho' they themselves had none. 5

There seemed to be a remarkable reluctance to call in the militia and give them the authority to forcibly disperse the mob. When troops arrived, there was often no magistrate at the scene of the riot prepared to give them the order to shoot. This arose because of a widely held belief that soldiers had no legal right to open fire on a lawless mob unless specifically instructed to do so.

Illustration from Barnaby Rudge by Charles Dickens (1841) which was based on the Gordon Riots

The end of the riots

By Wednesday 7 June, the number of troops in the city had swelled:

The guards being found to be insufficient to defend the various parts of the metropolis, all the troops and militia within thirty miles were, the preceding day, sent for. A strong guard was placed at Buckingham-house, now called the Queen's Palace, their majesties town residence. A camp was formed in St. James's-Park, and a detachment of the marching regiments of militia formed another in Hyde-Park. 6

According to Walpole, 12-14,000 soldiers were involved in quelling the tumults. These included those normally stationed in the city, such as the Horse Guards and the Foot Guards, as well as the militia from neighbouring counties.

The troops were ordered to fire on those who would not disband peaceably. Estimates vary as to how many people lost their lives in the riots. Hibbert estimated as many as 850; Pelham reckoned about 500. Some were killed by gunfire. Others died in fires or through alcohol abuse.

Illustration from Barnaby Rudge by Charles Dickens (1841) which was based on the Gordon Riots

Horace Walpole wrote to his friend, the Reverend Mr Cole, on 15 June:

You may like to know one is alive, dear Sir, after a massacre, and the conflagration of a capital. I was in it, both on the Friday and on the Black Wednesday; the most horrible sight I ever beheld, and which, for six hours together, I expected to end in half the town being reduced to ashes. I can give you little account of the original of this shocking affair; negligence was certainly its nurse, and religion only its god mother. 7

In a letter to the Earl of Strafford, Walpole wrote:

Religion has often been the cloak of injustice, outrage, and villany: in our late tumults, it scarce kept on its mask a moment; its persecution was downright robbery; and it was so drunk, that it killed its banditti faster than they could plunder. 8

What happened to Lord George Gordon?

Around 450 rioters were arrested, though only a handful were tried and convicted. Lord George Gordon was arrested and taken to the Tower of London where he was tried for treason. In Walpole’s opinion:

The Tower is much too dignified a prison for him — but he had left no other. 9

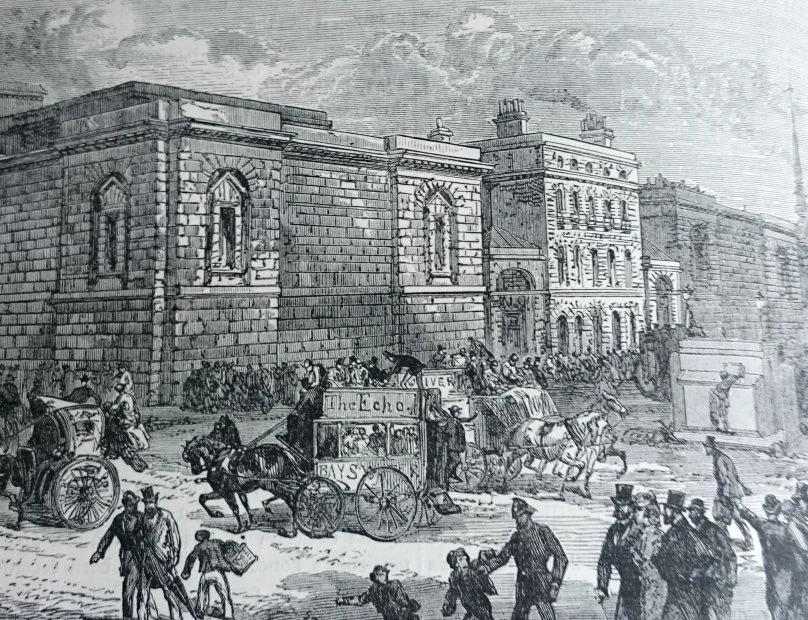

Lord George was found not guilty and released. However, the eccentric lord continued his extremist political activity and was later charged with publishing a pamphlet criticising the administration of justice and for libelling Marie Antoinette, the Queen of France. He was convicted on both charges and imprisoned in the rebuilt Newgate Prison where he died in 1793.

The front of Newgate Prison from Old and New London by E Walford (1878)

The Gordon Riots in A Perfect Match

The Gordon Riots play a small but important part in A Perfect Match. The hero, Christopher Merry, has never recovered from the trauma of what he witnessed during that fateful week. In his pursuit of love, he is forced to confront the truth.

Rachel Knowles writes faith-based Regency romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew, who co-writes this blog.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. Lady’s Magazine (1780).

2. Ibid.

3. Whitehall Evening Post, June 1780 from British Library Collection.

4. Lady’s Magazine (1780).

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Letter from Horace Walpole to the Reverend Mr Cole dated 15 June 1780 in The Letters of Horace Walpole.

8. Letter from Horace Walpole to the Earl of Stafford dated 12 June 1780 in The Letters of Horace Walpole.

9. Ibid.

Sources used include:

Dickens, Charles, Master Humphrey's Clock - Volume III - Barnaby Rudge (1841)

Gentleman’s Magazine (1780)

Hibbert, Christopher, George III (1998)

Lady’s Magazine (1780)

Pelham, Camden, The Chronicles of Crime or The New Newgate Calendar embellished with fifty-two engravings from original drawings by 'Phiz' (1841)

Walpole, Horace, The Letters of Horace Walpole, Earl of Orford, volume 6 (1840)

British Library Collection

Gordon Riots on Wikipedia – a comprehensive and well sourced article that checks out with other sources.

All photos © Regency History